Neko Case on Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters as Much Today as She Ever Did

On the Musical and Political Legacy of a Groundbreaking Singer-Songwriter

I hadn’t listened to Sinéad O’Connor’s records since the mid-’90s. Yes, I know how fucked up that sounds, I mean why wouldn’t I?! It’s really hard to explain, but I’ll try.

I was the human demographic The Lion and the Cobra was aimed at when it came out in 1987, but I resisted it. Why? Because I was a seventeen-year-old asshole. I hadn’t actually heard her music yet, but the hype was deafening, and I took that to be a red flag because I considered myself pretty fucking punk. (I fought hard for that feeling.) I also didn’t know yet that I wanted to be in a band, because I was a dumb fuckin’ girl and who would be into hearing me play? (Turns out I was not so punk.) I thought I already knew the answer to this question in my soul despite never actually asking it.

I was 24/7 tainted and obsessed with music. It was screaming in my face! But patriarchy is magnificent this way, a perfect predator. It told me without even trying that I would be an idiot for even thinking I could play music, and I had no idea what I wanted outside of a fairly narrow territory I was willing to explore anyway. And yes, I thought I was SUPER open-minded, but punk at that time was anything but. It was just more rigid conformity and patriarchy. Luckily, I had a lot of dear friends who were coming out and beginning to openly identify as queer, and something about Sinéad’s music was lighting them UP. I thought, OK, show me these goods. Commence with the Sinéad O’Connor.

It’s irrelevant if O’Connor herself is gay or straight or man or woman or they/them, because she sings it like an avalanche, with passion and abandon and desperation.

Within the first few seconds of “Jackie” I was trapped forever. She changes character in the middle of the fucking song! Her lower register takes you by the throat like a fist of smoke. Then, without warning, out of that delicious oily witch of a curse she goes straight into the dance club ripper “Mandinka.” My little mind was blown. Then, in “Jerusalem” she says she’s gonna fucking hit you if “you say that to me.” WOMEN WEREN’T SAYING THAT SHIT IN SONGS! Women and their issues with their own violence had no place to even be a thought, let alone be in a song on a massive hit record. It did not escape me. It broke a little something open for me.

By the time “Just Like U Said It Would B” asked “Will you be my lover? Will you be my mama-uh-uh?” I was openly weeping (and not just because somebody finally managed to sing the word lover and not make it sound unbearably stinky), because I heard her ask me as me, for me, as a female. It meant so much more than hearing a man ask it in a song—that happened all the time and they didn’t fucking mean it! Then I felt the deeper sympathetic crushing (the painful crushing, not the puppy love kind) my friends must have been feeling. I didn’t take my queer friends’ struggles for granted and I tried hard to be there for them, but I wasn’t having to come out for anyone. I wasn’t in a music and media desert where no one ever expressed their desire without fear of being shunned, canceled, excommunicated, or beaten to death for using the gender pronouns their hearts wanted to speak. I got a glimpse of how much more loneliness is possible, and how endless and horrible the varieties of neglect were, and I cried harder. I’m still crying about it today.

Back then nonbinary hadn’t really happened for the fringes, let alone the mainstream, and trans was not a term I fully understood. There didn’t seem to be any agreed upon terms? But in the song it’s irrelevant if O’Connor herself is gay or straight or man or woman or they/them, because she sings it like an avalanche, with passion and abandon and desperation, and she respects herself and respects all of us who could possibly be out there listening so hard to hear even a shred of ourselves in a song. The sacredness of vulnerability and intimacy is more religion than performance here.

One thing I’ve learned looking up Sinéad O’Connor’s career is how little I actually knew. Back then I had to rely on a cassette tape, and her occasional appearances on late night TV. I didn’t have cable TV (or any TV really), so I saw her videos from time to time at friends’ houses or random places. And in her early videos she’s just singing. Which is glorious! Yes! But she also co-produced her first record (and probably her second) and played a ton of instruments! I also could not afford rock mags and there was no internet, so if she ever spoke about songwriting and the instruments used therein, I had no idea. Not a clue. It would have meant so much to so many young people to see that.

Which brings me to her next album, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, which came out in 1990. “The Emperor’s New Clothes” was the second single but is SO much heavier to me than “Nothing Compares 2 U.” When I put it on the other day my first thought was, Can you fucking imagine being in the studio and hearing for the first time the opening count-in of HUGE drums and the rapid-fire staccato of muted guitar together suddenly fall off the cliff and land fully upright, mid-stride in an upbeat, jangling pop song?! And then Sinéad comes in?! I imagined myself in that control room and was (you guessed it) bawling.

Those are the moments we all hope for as musicians and engineers and producers. When they happen you feel like you could stop everything and walk out the door full-up and satisfied for the rest of your life. I cried at the mere thought of her possible joy twenty-two years earlier! Haha! I hope to God she felt it, because things like Grammys and Oscars can’t do that to you. You can remain at a distance from reviews and awards—from The Feeling you cannot.

She could have phoned it in and still sold millions of records; instead she’s singing (again) about her own life, her own personal violence, and she does not apologize.

Sinéad was a bona fide superstar by the time I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got came out. She could have phoned it in and still sold millions of records; instead she’s singing (again) about her own life, her own personal violence, and she does not apologize while singing about the rage hormones can put you through, pregnant and otherwise. I’d never heard a woman talk about this let alone SING about it before. I was raised watching biology-free Lawrence Welk with my grandmother for Christ’s sake! To my young, congealing, misogynist mind, pregnancy was not cool—it was “evil,” terrifying, the end of your life if you were female, and only for religious people.

Please keep in mind, I was feral and had no parents. Having a baby in my subconscious mind was abject fucking cruelty; in my conscious mind, it was nothing short of conformity and “giving up.” (Yes, I was fucked up.) She stopped me in my tracks. She ruled the world with “Three Babies,” a song about how an abortion actually makes her a better mother. It’s not a challenge, a threat, or a justification—it just is. I already felt this way, I understood abortion and my own fierce protective nature. I had just never heard anyone say it before, let alone so Grand Canyon–ly beautifully. I had permission to start thinking about not having to hate my own biology, slowly, in little bits. She started that for me. Her lyrics are so personal and often don’t rhyme. They hit harder for it—she speaks of the mundane and it breaks you. Out of the gate in “Emperor’s New Clothes” she’s brutally plainspoken about the realities of a relationship:

If I treated you mean

I really didn’t mean to

But you know how it is

And how a pregnancy can change you

She doesn’t apologize, nor does she absolve herself of responsibility, and that’s where the crushing tenderness lays so softly right behind that tired truth over an unrelenting dance beat. It’s fucking perfect, and it’s devastating. There is so much respect for the person she is speaking to (and herself) even though they may be in an impossible place. What a love song. It could have ended there and it would still be perfect, but then we wouldn’t make it to the line “I will live by my own policies,” so…

Sinéad O’Connor’s music is a gift I received from my persistent, loving friends. What a beautiful state of affairs. Most of us have “given” music to another person at one time or another and likely changed them away from some darker place, or just gave them some fizzy joy? It just never stops amazing me what that transaction can manifest. I think that’s why sometimes we don’t listen to a favorite life-changing record for years after wearing it out and committing it to muscle memory. It acts as a poultice—a medicine, some feel-good drugs and a Ziploc bag to keep it in for later, when you need it. When you open it again you may not be ready and maybe that’s when you need it most. It feels like the reason we stay alive.

__________________________________

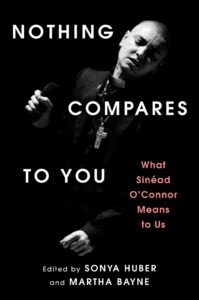

From Nothing Compares to You: What Sinéad O’Connor Means to Us, edited by Sonya Huber and Martha Bayne. Forward copyright © 2025 by Neko Case. Available from Atria/One Signal Publishers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Neko Case

Singer, songwriter, music producer, visual artist, and writer Neko Case has built a career with her distinctive style and musical versatility. In addition to her numerous critically-acclaimed and Grammy-nominated solo records, Case is a founding member of The New Pornographers. She authors the newsletter "Entering The Lung" and is currently composing the musical theater adaptation of an Academy Award winning motion picture. Case is also the author of The Harder I Fight The More I Love You: A Memoir.