Neil Gaiman on the Good Kind of Trolls

Introducing the Spellbinding Folktales of Norway

I keep trying to write a measured and sensible introduction to this book, and I keep failing. I keep failing because in order to find out what I think I pick up the proofs and start to read—or rather, at this point, to reread and to rerereread—any one of the Norwegian folktales waiting between these covers, and then I’m swallowed by them. I don’t read them critically. I don’t even put my compare-this-story-from-this-tradition-to-this-other-story-that-it-somehow-resembles hat on. I just start to read, and I’m following the adventures of Ash Lad, or the Girl Whose Godmother Was the Virgin Mary, and I feel satisfied.

Someone is telling me a story.

I first went to Norway in July 1998. I landed in a tired daze: I had flown to Oslo from Reykjavik, where the sun did not set and my hotel had no curtains, so I had spent most of the past three days awake. I managed a day in Oslo of seeing people, of drinking my tea where Ibsen drank his coffee, and eventually I was taken to my room in the Grand Hotel where the curtains, lined with black, closed, and in the glorious darkness I finally slept.

I woke refreshed, and had days of joy.

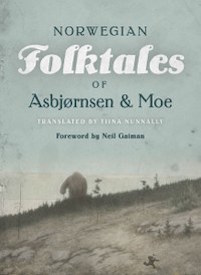

I was introduced to the art of Theodor Kittelsen (1857-1914), who drew trolls and the Norwegian countryside. Kittelsen was more than an illustrator or a folk artist, but he was not as well known as Arthur Rackham or John Bauer. His trolls made sense: they were as much a part of the world as the trees and the hills. His drawings and paintings felt as though they had paused in their travels for Kittelsen to create their portraits. I learned that Kittelsen was once told that a rival had decided to start painting trolls, and he had been puzzled and upset by this. “How can he draw a troll?” he asked. “He’s never seen a troll!”

The cover of this book features a painting by Theodor Kittelsen.

I was driven across the country, from Oslo in the southeast to Bergen in the southwest, passing through the Hardangerfjord region with its remarkable waterfalls, each a scenic joy. I found myself loving Norway. There was a wildness to the landscape that appealed to me, but it was a restrained wildness. I resolved to return.

Our sacred mysteries become myths become folktales, and Frost Giants and gods become trolls and heroes.

And return I do, when I can. I love Norway. There is a gloom in Norway that creeps out in the oddest places. I delight in the Emanuel Vigeland Mausoleum in Oslo, a candle-lit chapel where people sit in silence and wait for their eyes to become accustomed to the darkness, then they stare at the naked people and skeletons painted on the shadowy walls. Part of my delight is that the windowless red-brick mausoleum is quietly just another building in a pretty, tree-lined, residential neighborhood.

I encountered Asbjørnsen and Moe’s Norwegian Folktales sometime in the 1990s, and really enjoyed them. They were story types I was familiar with, but there was a focus and a chill, a way of bringing characters on stage, and a canny use of what W. S. Gilbert called “corroborative detail, intended to give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative” that engaged me. Still, the translation I read then was a century old, and it creaked at the edges, sometimes.

I was already in love with Norse mythology, and one can feel the shadows of the Frost Giants in some of these stories, or echoes of the tale of Thor and the Loki and the Thialfi of the contest with the giants: Asbjørnsen and Moe also sensed this and drew attention to it. Our sacred mysteries become myths become folktales, and Frost Giants and gods become trolls and heroes, given enough time.

In a translation as crystalline and pellucid as the waters of the fjords, Tiina Nunnally takes the stories that Asbjørnsen and Moe collected from the people of rural Norway, translates them, and gives them to us afresh. Each story feels honed, as if it were recently collected from a storyteller who knew how to tell it and who had, in turn, heard it from someone who knew how to tell it.

There are a great many sensible people in these stories. Quests are undertaken, disguises adopted, treasures returned with, royalty wed, yes. But there’s an ease and a community I love, as well as a way with stories. People seem—many of them—to want to help, and experiencing how information is doled out is a pleasure. Watch the young girl who cannot spin or weave or sew be rescued by three old women who can; all they ask is that she call each of them “aunt” on her wedding day. I have read dozens of versions of this story, but this is the first to conceal the information about the old women’s deformities until the dramatically perfect moment in the story.

You will meet youngest sons and foolish farmers, clever women and lost princesses, adventurers and fools, just as in any collection of folk stories from anywhere in Northern Europe. But the Norwegian Folktales come with trolls, and if Asbjørnsen and Moe did not see them, as Kittelsen did, then they got their stories from people who had, people who had seen the trolls walking in the mist at dawn.

________________________________

Foreword by Neil Gaiman from The Complete and Original Norwegian Folktales of Asbjørnsen and Moe, translated by Tiina Nunnally and published by the University of Minnesota Press, 2019. Foreword copyright © 2019 by Neil Gaiman. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman is the New York Times bestselling author of the novels Neverwhere, Stardust, American Gods, Coraline, Anansi Boys, The Graveyard Book, Good Omens (with Terry Pratchett), The Ocean at the End of the Lane, and The Truth Is a Cave in the Black Mountains; the Sandman series of graphic novels; and the story collections Smoke and Mirrors, Fragile Things, and Trigger Warning. He is the winner of numerous literary honors, including the Hugo, Bram Stoker, and World Fantasy awards, and the Newbery and Carnegie Medals. Originally from England, he now lives in the United States. He is Professor in the Arts at Bard College.