Nature’s Infinite Possibilities: Exploring the World’s Many Ways of Knowing

Mari Andrew: “With all that extra free space to wiggle around in science, philosophy, and magic, who knows what we’ll discover?”

I recently read an article about displaced oysters. These poor tykes grew up on the damp, textured beaches of Connecticut, but were taken mid-life to the golden fields of the prairie by a scientist named Frank Brown.

Frank had a keen fascination with mollusks. He kept them in a darkroom three hours north of Chicago and studied them attentively day and night.

Frank knew that oysters are most active during the two high tides of the day, which is when the water becomes an all-you-can-eat plankton buffet, and he wanted to see what they would do if they were hundreds of miles from the nearest sea.

For the first couple of weeks, their feeding schedule kept time with their home beach in New Haven. Turns out you can’t take the Nathan Hale Beach out of the oyster, or however that saying goes.

But what the homesick critters did next left him gobsmacked. Over the following weeks, they adjusted their mealtime to be later and later. This was a big puzzle for Frank until he consulted his almanac and considered the moon.

High tides occur each day when the moon is highest in the sky or lowest below the horizon. Frank figured out that the oysters were enjoying their plankton binge when Evanston, Illinois, would hypothetically have a high tide.

When I think of listening in order to understand, I imagine my entire body orienting toward the subject at hand: a bed of moss, a ladybug, a high tide filled with feasting oysters.

Locked in a Midwest darkroom with no light or any other cues from the outside world, the oysters were still in touch with the moon.

Frank was elated to share this news, but he was met by critics who wanted his work scrubbed out of their field for not being “scientific enough.” His colleagues weren’t as open as he was to the perceptive abilities of other creatures; their field was a product of the Enlightenment, where rationality ruled and everything else was baloney. Frank became the butt of a joke about what happens when you stray from common sense. “You know the guy who thinks oysters get signals from the sky?”

But our friend Frank doubled down! He began studying the metabolic rate of potatoes, which, despite being isolated from their farms of origin, could also clearly sense the hour of the day and season of the year.

He eventually claimed that all living things must be sensitive to all kinds of signals, even forces that hadn’t been discovered yet by humans. Life was pulsing in time with earth, and all its organisms were bathed in subtle rhythms while the planet spun.

Though Frank’s evidence was concrete, he joined the legions of mystics, visionaries, prophets, intuitive empaths, shamans, medicine women, revolutionaries, sensitive souls, and anyone with a special connection to the land and animals, whose ideas have been laughed at and dismissed throughout history.

While I don’t assume Frank was exactly a flower child, it was a radical claim that oysters could sense something beyond the secured tubs of a dingy underground lab, and—likely much more threatening—that humans weren’t able to sense it.

How dare a scientist hint that the world’s wonders are not necessarily explicable and may not even be perceptible to human beings?! By insinuating such, Frank practically committed blasphemy against Reason.

Decades later, nobody knows what to make of these calcified invertebrates and their moon-sensing magic. Because oysters must be so highly attuned to something we can’t perceive, we may never fully understand it.

*

An interesting thing happened in my dance class the other day.

I’ve immersed myself in dance this year—sort of accidentally. While joining a friend at hip-hop aerobics, I remembered a joyful feeling that had lain dormant in my soul since the last jazz class I took twenty years ago. Now I go to four classes a week, and I’m often the oldest, usually the worst, and always the smiliest participant. Dancing gives me a feeling I can’t explain, but if pressed, I’d say it has something to do with expressing a part of myself that never gets released in daily life.

As of late, I’ve used dancing to express emotions that don’t naturally slip into the spaces society has carved out for feelings. This last year, I’ve been fiddling with several Rubik’s Cubes of complicated grief. I’m grieving my beloved stepdad whose loss can’t feel like mine as long as people ask, “How’s your mom doing?” but never ask about me. I’m mourning the death of a friend who struggled with depression for years—even though we hadn’t talked during all those years. I’m growing apart from a close relative and out of some beliefs I’ve been attached to for years.

These puzzles prick me with pain all day long, but they’re not easy to describe. Sorry I didn’t get back to your email, I was lying on the floor in a starfish position thinking about a Facebook status my dead friend wrote seven years ago, and it really put me in a funk.

So, instead of explaining my feelings, I dance my feelings. I dance out grief, grace, survivor’s guilt, giddiness, resentment, and everyday annoyance. More often than not, I pry myself out of a crowded subway and stumble into class announcing, “I want to scream at everyone!” By the end of class, I’m euphoric enough to consider high-fiving everyone.

The other day, a neurologist came to class. Inspired by some articles suggesting that dance could be a treatment modality for some mental disorders, she observed our moods and took furious notes throughout class.

I wasn’t surprised because, of course. Of course dance is a treatment modality. Of course dance improves our mood. Of course it fosters connection, tightens community, metabolizes emotion, releases stress, increases confidence, etc. etc. etc. etc. We’ve only been doing this for hundreds of thousands of years.

The need to study and prove the benefits of dance amused me. I wanted to tell the neurologist, “Why don’t you just try it…okay, there, that’s your proof!”

It also made me a bit sad. There are so many exciting phenomena on this gloriously strange planet we’ve found ourselves upon, and so many of them is knowable if we choose to accept that there are many different ways to know something.

From the deepest part of me—the part that feels connected to chanting ancestors in a Nordic forest that I will never visit, the part that wails in grief when I don’t care who hears it—I know dance is healing me. I don’t need to appease my finicky brain with studies and statistics and proof. I feel it in my feet, and that is enough.

I also don’t need written proof that there is aliveness in rocks and water, or that trees have families, or that animals care for one another. I know all that.

The things I’ve “known” in this particular way—in my belly, as though I was born knowing them—have served me the most. The things I’ve learned with my mind? They’re the ones that change over time and most often disappoint me.

The neurologist at my dance class reminded me of how I will often seek evidence that something is, in fact, good for me even when it feels good for me. More energy, better sleep, and sustained vibrancy isn’t enough. I’m over here googling “Is a plant-based diet better for you?” I’m willing to give away my own power of intuition the minute I get on my keyboard in order to fact-check my own instinct.

*

I wonder if this is what Frank Brown was up against when his fellow biologists were mad at him for noticing that oysters boast a strong relationship with the moon. Why would this be so astounding in a world with lavender skies, green-sand beaches, hundred-pound rocks that sail across deserts, a volcano that burns blue, and another that erupts with ice?

For some of the wildest and most beautiful phenomena in the world, the scientific explanation is inconclusive. Yet somehow we understand it all from the ancient depths of our bellies.

I learned a word for this: “transrational.” It means “going beyond or surpassing human reason.”

Modern Western science would likely teach that irrationality is the opposite of rationality. But what if they weren’t opposites? What if modern science was expansive enough to hold the idea that there are wonders and miracles and oyster habits that go beyond what we can comprehend in a science-y way and yet we can still believe them?

Take “love” for instance. Can anyone define it? Greek philosophers and fifties teenage crooners alike have tried, and it all comes out sounding pretty corny, even trite. There is no scientific explanation of love that anyone can agree on. My definition may vary from yours or from Whitney Houston’s or John Keats’s, but it doesn’t matter. The world seems to intuitively agree that love doesn’t need to be delineated to be understood.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, botanist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, points out that science refines the gift of seeing, quite literally through various lenses like the magnifying glass or microscope. But science looks only at the material being.

In contrast, she says, “In Indigenous ways of knowing, we say that we know a thing when we know it not only with our physical senses, with our intellect, but also when we engage our intuitive ways of knowing—of emotional knowledge and spiritual knowledge.” Rather than looking, traditional knowledge teaches us to listen.

When I think of listening in order to understand, I imagine my entire body orienting toward the subject at hand: a bed of moss, a ladybug, a high tide filled with feasting oysters.

I listen with my belly, with my teeth, with my knees, and with every cell of mine that can perceive. I remind my brain to take a rest and withhold the commentary. And sometimes after a couple minutes, sometimes after years, the “knowing” comes so easily:

Of course oysters can feel the pull of the moon, even from a landlocked darkroom. If I listen long enough, it’s so logical that I’d be surprised if it weren’t the case.

Of course dung beetles navigate using the stars; they roll their dung balls along straight paths under starlit skies—but not in overcast conditions.

Of course termites use their heads to drum in order to signal danger to other termites. As soon as they perceive a threat, they begin, and those who hear the drumming also start drumming so as to help warn as many termites as possible.

Of course orangutans have the wisdom to self-medicate with what’s available to them. When wounded Sumatran orangutans make a paste from a native plant known to locals as having healing properties and chew the leaves for good measure. Is this intuition, learned behavior, evolution, or spiritual inkling? Does it matter?

Notice how you never come across a study that concludes, “Animals are actually stupider than we think!” The more seekers of all kinds of knowledge (poets and scientists alike!) investigate the inner world of nonhuman creatures, the more magical we realize they are.

*

I’ve noticed an abrupt change in my thinking during the past couple of years. While I could once feel the firm grasp of my mind on her many opinions—as rigid and unchanging as rock formations on the beach—my brain seems to have loosened up. My whole body feels looser (for better or worse), and I can sense more spaciousness within me. There is a lot more space for contradictions, conflicting ideas, and fresh questions to old answers.

Some days, it’s exciting: my mind’s eye is watching a minimalist black-and-white painting become smudged into finger-painted gray. With so much streaky uncertainty, I feel younger than I did fifteen years ago when I knew I was right about everything.

Other days, my identity is shaky without such strong feelings propping it up. Unwavering morals that once led me to boycott, ban, and boast about my behavior now flex and stretch beyond recognition.

I find myself shrugging a lot more. And answering, “That seems true.” And saying the exact same thing to the opposing argument. Rather than my beliefs becoming sharper and more finessed, they’ve become rather dull. I’ve found myself concerned about my apparent apathy and disinterest in picking fights.

On the flip side, I’m an easier person to be around. I don’t cut people off because they have different recycling habits. I feel a lot calmer, while simultaneously being more curious. I like inhabiting a more spacious self.

When I consider Robin Wall Kimmerer’s broad definition of “knowledge” as both seeing and listening, I imagine my life gently divided into two halves: the first, intent on seeing; the second, devoted to listening.

Funny how maturity so often looks like returning to childhood, when possibilities were so much bigger than they ever are again.

Young people are blessed with the passionate drive to see. They notice everything, and name their observations plainly, without hesitation. They show our world to us. Sometimes our eyes become too groggy, even crusted over, so that we are no longer really looking at the world but rather just passing through it. Young people alert us to what’s wrong.

But maybe the sense I’m honing as I get older is listening. Listening lets me in on a different way of knowing, one that isn’t intent on concluding as much as it is on simply experiencing.

When I experience the sensation of dance, I’m open to its magical transformative powers, powers that defy vocabulary. While experiencing an encounter with an animal, I’m open to its sacredness. At dinner with a friend, I’m open to this sliver of his life and his vast mind and the comingling of our beliefs.

The priest Richard Rohr talks about living with lightness and inner freedom in the second half of life. He writes that the universe has the opportunity to surprise and enchant us once we give up control. As we grow up and age, we realize that we could never plan for joy; it only comes through spaces we leave when our life is loose enough to notice it in the first place.

We learn over time that planning the perfect party is often a bust, and the best times are usually unexpected. In a loose life, nothing can be held too tightly—neither plan nor perspective. It’s only then when a person is able to press their ear against the heartbeat of their life and listen with full intention.

*

Any time I am ambivalent about loosening my grip on so many strongly held convictions of my more radical youth, I recall oyster enthusiast Frank Brown and soften toward acceptance.

Because of his spacious mind and loose life, he was completely open to the idea that mollusks would track the moon’s movements even when it seemed—given human limitations—impossible to do so.

Impossible, sure, but they were doing it! This clearly delighted Frank, as he kept listening to all kinds of beings across a range of aliveness throughout his career, even while his colleagues thought his spacious imagination—and all the magical findings he entertained—didn’t belong in science.

If growing older means becoming looser and more spacious in our thinking, perhaps science is also becoming roomier. People like Robin Wall Kimmerer invite us to expand how we even define knowledge, as do so many other biologists from backgrounds that Western scientific fields have too long ignored or overlooked.

Funny how maturity so often looks like returning to childhood, when possibilities were so much bigger than they ever are again. Little kids don’t separate subjects into clean spaces on a school schedule: this is fact, this is poetry, this is spirituality.

Instead, they, like Frank, see it all as the same—unnecessarily separated by textbooks and experts. Why can’t philosophy belong in math, which can belong in literature, which can belong in biology, which can belong in what used to be called “sorcery”? There are as many ways to perceive the world as there are beings on this world. We won’t be privy to them all in this lifetime, but we can start by loosening our lives. It doesn’t have to happen dramatically all at once, of course. It can be just a bit here and there. A roomier conjecture. A more spacious opinion. Just enough expanse to think about considering the fact that an oyster can perceive the gravity of the moon. Just that. And then, with all that extra free space to wiggle around in science, philosophy, and magic, who knows what we’ll discover?

__________________________________

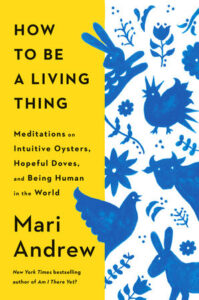

From How to Be a Living Thing: Meditations on Intuitive Oysters, Hopeful Doves, and Being Human in the World by Mari Andrew. Published by Penguin Life, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Mari Andrew.

Mari Andrew

Mari Andrew is a writer, artist, and speaker based in New York City. She is the author of Am I There Yet? and posts her writing and illustrations on Instagram at @bymariandrew.