At last it had happened. The decision to kill Petula was one Regan and Jazzy came to on their own, without conference or the faintest notion that the other sibling was being edged towards the same desperate solution to what neither guessed was a shared problem. Nor did they hold the thought in its raw and reductive form, instead discovering, like a tadpole in a petri dish, that it had been growing unwatched all along—Regan believing she loved her mother right up to the night she saw she hated her, and Jazzy long entertaining the notion that nothing would change until his mother passed, without recognising he willed that day on with all his heart, until it was forced from him. Theirs were separate journeys, taking very different routes, made at contrasting velocities, the slower reaching its goal faster, and the quicker drawing the same conclusion later; speed for once being of no account in this race to a conclusion neither had forewarning of.

Like a voter who puts a cross beside the same colour at every election, Regan was too party-orientated to question the self-evident truth that her mother was wonderful, the pace at which she attacked life preventing her from focusing on the passenger left on the platform, in this case herself, mouthing back the opposite of what she thought was the truth. Jazzy, on the other hand, had less distance to travel, nursing so many conscious grievances against his mother that it was an effort for him to think of anything else, from the time he brushed his teeth, to passing out; the shock for him not that he hated Petula—he believed that all along—but that he loved her, and it was because he did that the only course left open was to stop her from hurting him any more. Their decisions, however, were identical in the relief they brought.

These decisions once accepted, neither brother nor sister had cause to consult the past again, question the righteousness of their motivation, or blame coincidence or bad luck for the parlous desperation that drove them to leave the world they knew, and enter a secretive hell in which their most intimate imaginings and longings lay beyond the law. Both had heard it said often enough that if this or that had not happened, a certain conversation not overheard, the wrong bit of gossip not shared, the rain having fallen on that day rather than on this, then destiny would have happily resolved its tensions in a way compatible with everlasting satisfaction. This they no longer believed. The tale that life had fallen foul of malevolent chance, altogether too rosy and itself worthy of a Hardy novel, was pushed by their aunt Royce in an attempt to build bridges, without straying anywhere near the sore core of their purulence, her optimistic characterisation of their dissatisfaction as accidental, too hopeful by far. Royce would have been better served consulting the Russian novelists of the nineteenth century. Here she would have found a pushy and inexorable fatefulness, born of an eternally present horror, capable of being challenged at any time and therefore tragically stoppable; had there actually been a possibility of the challenge succeeding and tragedy avoided. Regan and Jazzy lived through slights, slings, tedious lunches and spontaneous gatherings, where all it should have taken was to ask Petula what the hell was she doing and could she please stop, to prevent the fall into criminality. Simple as this sounded, Jazzy and Regan had danced to variations of this tune for years, forever slipping up on the oily blatancy that underwrote their mother’s rule. All Petula had to do was simply deny that she knew what they were talking about and that there was any problem at all, only a mania the siblings had built up in their own minds, which is exactly how it would look to others once she had knocked their paranoiac querulousness into touch, and followed through with a speech that would shut them up for another two years. Regan and Jazzy would still be stuck with a version of themselves they despaired of, to be endured until its cause had gone, or, more likely, by their dying first (having never really lived), their mother scolding the undertaker for being late and reciting the funeral addresses over their coffins to a Cathedral packed full of her chums.

The step from conceding that only death, the black attendant, terrible and unconditional, would stop Petula from enjoying the last word, having exhausted the civilised problem-solving consensus, was a stroke from admitting that beneath this thought breathed another, with a crucial prefix: nature could not be expected to act on her own—if they were to enjoy the carefree mornings of a Petula-less future, it would need help. They would have, sooner or later, to pick up the slack reigns of their personal agency, otherwise Petula was going nowhere and nor, more as to the point, were they. Doing something in this context did not yet mean murder, and might even have entailed being able to persuade Petula to up sticks and leave the country, or convince her to simply leave them alone to live undistinguished existences away from her orbit and interference—these un-fatal remedies quietly suppressing the one true solution over a decade of wishful prevarication and second thoughts, matricide still too preposterous for them to contemplate.

Outwardly none of this was obvious, the slide towards barbarity concealed behind the dignity-sapping patronage that suggested a misleadingly cyclical picture of life at The Heights continuing without interruption. For his well-wishers—Jazzy had retained his gift of cultivating enduring pockets of sympathy—there was enough to celebrate in the solid and joyless progress he displayed on the farm, tackling chore after task, supported by Spider and their cottage full of her children. With a dogged persistence luckier people showered in cheap praise, and a firm handle on the irruptions that had previously played havoc with his nervous system, Jazzy applied himself to a life nearly free of hope, ambition or direction, and in this way was closer than ever to the peasants of the past he imagined a kinship to. With muted satisfaction, he observed how well he could manage his days without being inspired, stimulated or particularly happy, a competent and fierce worker; loyal too, as there was no question of his ever labouring for anyone anywhere else, the slow pace of his achievements—a bodged door that saved Petula the cost of a replacement, hedges trimmed like crew-cuts and drains as leaf-free as the trees they fell from—marks of a hair-splitting thoroughness that not even his mother could dismiss the solidity of.

Occasionally Jazzy would disappear without a word for an afternoon, adding to his portfolio of tree sculptures dotted round the grounds. An old oak suffered creatures like those he moulded as an adolescent carved into its trunk, while a totem pole of related freaks appeared at the base of a red beech by the lake. An outbreak of experiments with the branches of ash trees, sharpened like spears, followed, and a quintet of small conifers were turned upside-down and stuck back in the earth to mark his fortieth birthday. These playful forays in to wood-art led to Jazzy’s eventual pièce de résistance, the result of several months’ covert labour and one weekend’s noisy construction work. With stubborn meticulousness Jazzy had set about a cluster of birches and stripped them of their bark, uprooting and replanting them over forty-eight hours by a remote south-facing border of the property, the straight line of trees pointing like cruise missiles to a world beyond The Heights in what may have been a homage to either war or peace, attack or defence. His feat took those few walkers who saw it by surprise, whilst causing no one any offence, and very little comment, Petula slyly not giving her son the pleasure of raising even the slightest objection to his relocation of natural resources. Soon after that Jazzy sulkily switched back to the creation of small moulds, this time mostly in the form of elves and fairies that he sold at local markets with Spider’s jams and cordials, the resemblance between these figurines and his old girlfriend, Jill, obvious to those few who still remembered her.

There were other more prosaic changes. Jazzy was no longer considered a ‘colourful’ character, at least as far as his clothes and physical appearance were concerned. Turning his back on the harlequin garments and loud togs of a medieval troubadour, Jazzy submitted to overalls and construction boots like any other mid-life labourer, his earrings, nose ringlets, Celtic bangles and love beads vanishing, the best of the trinkets going to Spider’s children, their original owner content to blend into the ordinary and unremarked-upon world of the average man. The relaxed drift towards an assimilation with his surroundings was roundly welcomed by his neighbours, Jazzy finding that middle age was not the cruel trick he had been warned of, rather a condition unusually suited to his staggered acceptance of ennui. Naturally he would have preferred life without the patch of scarlet veins that shot up in rivulets under his cheeks, the shying of hair, which fell in twisted clumps once the dreadlocks were untangled, and disabling pain that broke out in places he had taken the obedience of for granted. All that was as miserable as it would have been for anyone else, his fierce work ethic alone disguising the full extent of the maladies that functioned as a tag team, one ailment passing the baton to the next in an uninterrupted slow roll of illness and aches. Indoors, Jazzy would lie on the saggy, battered old couch, salvaged from one of Petula’s spring cleans, and groan, but outside, the general levelling particular to survival into his fourth decade heralded doors, albeit it narrow ones, he welcomed the opening of.

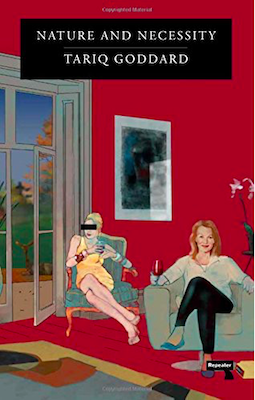

From Nature and Necessity. Used with permission of Repeater. Copyright © 2017 by Tariq Goddard.