Natalia Theodoridou on Unraveling a Short Story into a Novel

“It gave me permission to indulge myself and my characters.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

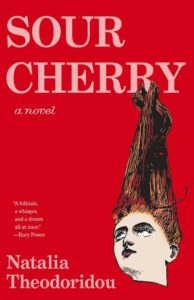

I spent the better part of the past decade thinking of myself as “strictly a short story writer.” My debut novel, Sour Cherry, started out as a short story, loosely based on the Bluebeard folktale: Cherry Girl lived with a man who kept his previous wives’ bodies in the little back room of his rotting house. There was a Cook, who cared for him. Together, Cook and Cherry Girl picked up after the man and the devastation he created: the scattered beads, the crumbling leaves, the blighted land. I was fortunate to workshop the story with Karen Joy Fowler—a generous and thoughtful reader. Among the many wise things she said in her feedback, she also said this: “I want to know more about Cook. There’s something there.”

What was there turned out to be an entire novel.

Short stories took a long time to hatch in my head but then would emerge almost fully-formed and in need of minimal editing or restructuring. For me, writing was most definitely not rewriting. In edits, I usually found that the lace of the story was so tightly woven that, if I tried to alter anything substantial, the whole structure was compromised. I lost resonances that seemed to have made it into the text without my conscious planning. The experience of writing a short story felt to me like a long gestation resulting in something peculiar that should be nurtured but not disturbed.

What if I could retain the sense of multiplicity I had found in interactive fiction? What if the process could be not one of restriction and chiseling but of proliferation and blooming?

By comparison, transforming this material into a novel felt like trudging knee-deep into the guts of something I had pulled apart, rolling around in the gore trying to reconstruct the eviscerated thing into a new kind of monster. There was so much space there, now. I could move things around freely, and, instead of having the structure crumble, I discovered new rooms had sprouted spontaneously while I wasn’t looking, then sprouted again while I was, like dividing cells, like new growths. Some of these proved vital; others I later had to lop off, which felt much less painless than I had anticipated. To get from short story to novel, I went over the material tugging on every thread I came across. Where was Cook before she came to live with Cherry Girl and her man? Who was she before she lost her name? And what about the previous wives? What about the very first? This didn’t simply extend the narrative but brought forth what it already contained, like a reverse unravelling.

Before I focused on Sour Cherry, I was also writing long-form interactive fiction where the reader, as the main character of the story, is constantly presented with choices about how to proceed, what to say, what to think in response to the text. At every juncture, I would map all the different ways the characters could move through the narrative. But in this non-interactive story, I had to pick just one of those options; as if playing my own book, it was on me to choose the best option on behalf of readers. All possible states in which the book existed had to collapse into one, as if my job was to whittle down the possibilities until a single branch remained, to chisel away until I found the real story buried underneath. Only the essential belonged. The process started to feel terrifying, the economy of it constricting. What if I made the wrong choice?

Fortunately, I was reading Matt Bell’s Refuse to Be Done at the time and came across Jane Smiley’s idea that “every great novel offers incomprehensible abundance.” The words rang me like a bell. What if I could retain the sense of multiplicity I had found in interactive fiction? What if the process could be not one of restriction and chiseling but of proliferation and blooming? (What if stories are like houses are like organisms are like lace?) It gave me permission to indulge myself and my characters, to run after our fancies and follow the free-associating thread of our thoughts.

This expanded the book outwards as well as backwards, allowing me to nod at the wealth of material that motivates every single choice we make and, in the end, props up a life. The linear narrative started to feel branchy again, not so much in its approach to plot as in its disposition. So much of what I love and what interests me made it into the novel, not as intrusion but as an uncovering of what had always been there. For me, intertextuality is not simply a device; it is at the heart of the creative process (which includes both the writing and the reading of the work). Sour Cherry is, after all, a retelling of Bluebeard, but what Bluebeard means to me is not just the French folktale; it is also Béla Bartók and music, it is tanztheater, it is #metoo and all the personal narratives it voiced.

And from there, all my background as a student of theatre poured into the book, because all the world’s a stage, and we learn how to be by telling each other stories, and our canons dictate the breadth of what those stories might be, so of course there would be Shakespeare here, too, and Brecht, and Greek tragedy haunting me at every turn. The book became truly dialogic, in the way Mikhail Bakhtin understood dialogue: in writing it, I was conversing with the work that’s fed me, cataloguing all my debts—because there is no thinking “I,” no writing “I,” except in relationship.

How fitting, then, that the starting point of this novel was also a moment of dialogue, an invitation: “What else is there? Tell me more.” All I had to do was be open to the incomprehensible abundance in response.

__________________________________________

Sour Cherry by Natalia Theodoridou is available via Tin House.

Natalia Theodoridou

Natalia Theodoridou is a queer and transmasculine writer whose stories have appeared in venues such as Kenyon Review, The Cincinnati Review, Ninth Letter, and Strange Horizons, and have been translated into Italian, French, Greek, Estonian, Spanish, Chinese, and Arabic. He won the 2018 World Fantasy Award for Short Fiction and the 2022 Emerging Writer Award by Moniack Mhor & The Bridge Awards, and has been a finalist for the Nebula award multiple times. He holds a PhD in media and cultural studies from SOAS, University of London. Born in Greece, with roots in Georgia, Russia, and Turkey, he currently lives in the UK. Sour Cherry is his first novel.