My Year of Reading Every Ursula K. Le Guin Novel

Susan DeFreitas on the Lessons of Le Guin During a Pandemic

If you’re lucky in this life, you may discover an author whose work moves you so deeply that reading it is like going to church—like listening to your own soul speaking quietly as you turn the pages. If you are luckier still, this author will be at least as old as your mother, astoundingly prolific, and will have published so many novels that reading them back to back will take you well over a year.

If this time period happens to fall during a global pandemic, so much the better.

I spent the better part of 2019 and 2020 immersed in the work of the great speculative writer Ursula K. Le Guin, and during this time, as my external world grew smaller, my internal world expanded. Even as I traced the same route through my neighborhood each day, I was sailing through an enchanted archipelago—and in a time when travel had become impossible, I voyaged among the stars.

Though in a way you could say Le Guin was always with me. My mother read the first three Earthsea novels when she was pregnant with me, and when I began to work my way through my parents’ collection of science fiction and fantasy as a tween, those slim, sepiaed paperbacks with their iconic covers—depicting a dragon, a sail boat, and a castle upon a stylized island—couldn’t help but catch my eye.

The Earthsea novels are set in a world where words are, quite literally, magic, and I loved them, the way so many young writers do. But I loved the work of many authors I found there on my parents’ shelves—authors like C.J. Cherryh and Anne McCaffrey, Patricia McKillip and Stephen R. Donaldson. The Earthsea novels were among the most beloved of my childhood, but they did not suggest to me, on first read, the larger scope of Le Guin’s vision.

Each of these books challenged me to reimagine what human culture might look like—challenged me to imagine how we might throw off the death grip of capitalism, and its attendant values of patriarchy and racism.

I would discover that more than 20 years later, when I moved to Portland, Oregon, to pursue an MFA in writing. Portland is a literary town, home to many famous names, but I soon found that none loomed larger than that of Ursula K. Le Guin, who’d lived there for over five decades. As a feminist, pacifist, and environmentalist, as a pioneer of what we might now think of as queer identities, and as a writer inclined toward anarchist thought, her work, more than any other, seemed to embody the spirit of the city.

At that point, I figured it was time to read the science fiction novels she’s famous for, The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed—both of which struck me with great force. Which led me to wonder: Could the rest of her work possibly be this good? When I searched the shelves at Powell’s, the only other books I found by Le Guin were a fantasy series with super-cheesy YA covers—the trilogy known as the Annals of the Western Shores, which encompass Gifts, Powers, and Voices—but I figured, what the hell.

I found that each of these books, just like Left Hand and The Dispossessed, challenged me to reimagine what human culture might look like—challenged me to imagine how we might throw off the death grip of capitalism, and its attendant values of patriarchy and racism. In each of them, I was transported by Le Guin’s prose—lyrical and rich and deliberate in its rhythms. And in each one of them, I found, there was a scene I stopped to reread, sometimes more than once—a scene so powerful it actually moved me to tears.

Even as I struggled in my MFA program, trying to find models for the type of realistic fiction I wanted to write—environmental fiction, centered on the sorts of people who were pitting themselves against climate change—I kept returning to Le Guin’s work, not just an escape from the pressures of this world but as a source of moral courage in grappling with them.

And so, when Le Guin passed in 2018, I knew I had to do something to honor her legacy. Since graduating, I’d been working as an independent editor, so editing an anthology of short fiction in tribute to her seemed like a fitting way to do that. And if I was going to do justice to the great lady, I figured, it was time to read all of her books.

It proved no minor undertaking, as Le Guin is the author of 24 novels and 10 collections of short fiction, not to mention her many essay collections, works of criticism, and books of poetry.

In the spring of that year, I was the writer in residence for Fishtrap, a literary organization based in Eastern Oregon, which Le Guin herself helped to establish; to honor her, Fishtrap had deemed 2018 the “Year of Ursula” with an entire year’s worth of events. In observance thereof, the local bookstore in Enterprise had assembled all of her books in one magnificent window display, and as a birthday present to myself, I purchased 11 of them, a huge extravagance for me at the time—and though I left the store that day over $200 lighter, I felt rich in a way I never had before, or have since.

That stack formed what I came to think of as my dragon’s horde of Le Guin’s fiction, and by the spring of 2019, when we went into quarantine with Covid-19, it had grown to include all 24 of those novels and 10 short story collections.

The crown jewel of that literary horde was the ominibus of the Earthsea books, a collection of all five novels and 10 short stories set in this world—complete with a fantasy map, Charles Vess’s fine illustrations, and its own yellow ribbon bookmark—that easily weighs north of four pounds. (During the period in which I read it, I had a seat solely dedicated to that endeavor; the book was too cumbersome to move from one spot to the next.)

Le Guin often said that she had no real command of plot; the best she could do, she said, was to have someone set off on a trip and then come home again. It’s a pattern I found upon rereading A Wizard of Earthsea, in which the protagonist, the young wizard Ged, sets off on a mission to confront his own Shadow, which is wreaking havoc on the land, and in the end, returns to the Isle of Roke.

The journey, and the return, and the impossibility of return—as I read further, I began to see that this was in fact a key feature of her world building among the stars as well.

I found it too in Le Guin’s experimental novel set in a future version of California’s Napa Valley, Always Coming Home. In the story at the center of this novel, which is structured largely like an anthropological survey, the character Stone Telling leaves the peaceful Valley of the Na to go live among her father’s people, the warlike People of the Condor, and in the end, as the title suggests, comes home, to raise her child.

Likewise, I found, this pattern in Le Guin’s very first novel, Malafrena—which, aside from taking place in the fictional Eastern European country of Orsinia, is a realistic novel set in the late 19th century. In it, the protagonist Itale Sorde leaves his family’s estate in the Malafrena Valley and goes to the capital city of Krasnoy to support the cause of independence from Austrian rule; in the end, having lived through imprisonment and revolution, he returns home.

It’s a pattern Le Guin herself acknowledges in the introduction to Malafrena, newly reissued via the Library of America, noting that it occurs also in The Dispossessed, in which the protagonist Shevek, a scientist, leaves his people on the anarchist moon of Anarres, travels to the capitalist planet from which they emigrated, Urras, and, in the end, returns home again. In 1975, the year after The Dispossessed was published, she wrote in her journal:

The queerest thing is that [Malefrena] is The Dispossessed, much much more than I realized when writing the latter: not only the person and the situation, but, the words: —True pilgrimage consists in coming home—True journey is return—and so on. I have not a few ideas. I have ONE idea.

But for Itale—just like Stone Telling, Ged, and Shevek—the home he returns to is not the one he left, because the journey has changed him, remade him as a person. And this too is a theme, I found, that runs deep in Le Guin’s work, and one Le Guin herself was very much aware of.

In the last interview Le Guin gave before she died in 2018, she noted,

There’s this whole difference between the circle and the spiral. We say the Earth has a circular orbit around the sun, but of course it doesn’t. The sun moves too. You never come back to the same place, you just come back to the same point on the spiral. That image is very deep in my thinking.

It’s a concept that resonated for me during the pandemic, rereading those Earthsea books, which I’d loved so much as a kid: they were the same but not the same, and how could they be? I’d packed a lifetime’s worth of experience between those two points of time, having lived, loved, and lost, traveled and studied and moved and married and settled.

Moreover, I found, as I read further into this series, Le Guin herself goes back over the same ground established in those early Earthsea books and remakes the world in which they’re set. In Wizard, we learn the phrase “weak as women’s magic, wicked as women’s magic,” and are made to understand that the truth that saying conveys is the reason the great school of magic on the Isle of Roke is open only to men. In Tehanu and Tales from Earthsea, however, we learn that women’s magic is not only as strong as men’s, but that the school at Roke itself was actually established in no small part by women, and the fact of this intentionally buried by men in a patriarchal bid for power. In these later books of the series, I returned to the place where I started with Le Guin, that enchanted archipelago, but found it was not the same place at all.

The journey, and the return, and the impossibility of return—as I read further, through Le Guin’s many novels and short stories set it in the Hainish universe, I began to see that this was in fact a key feature of her world building among the stars as well.

A central institution of the Hainish universe is the Ekumen—an organization similar in many ways to Star Trek’s Federation, in that it has a mission to explore the cosmos, but different in having more of a sociological bent. The Ekumen is a federation of worlds that upholds a code of ethics regarding the rights of sentient beings, and it seeks to bring new worlds and cultures into its fold, but it also has pretty strict directives on noninterference. As a result, a key tenet of its work is sending trained Observers to embed themselves in pre-contact worlds and cultures slowly, if possible, bring them around to the possibility of a peaceful co-existence with extraterrestrials—and, hopefully, to adopt the Ekumen’s code of ethics.

The majority of Le Guin’s stories set in the Hainish universe riff on such missions and the conflicts that arise from them, with protagonists, more often than not, who are themselves Observers. The prospect of which can’t help but seem thrilling at first, just the way the prospect of joining the Federation would: Get off your podunk, provincial planet! Travel to distant worlds! “Go boldly where no man has gone before!”

But in Le Guin’s universe, there’s a catch, and it’s a big one: There is no faster-than-light travel—which means that you can leave home, but, thanks to Einstein’s theory of special relativity, you can never go back (at least to the time frame you left behind).

It’s a world building decision, I found, that results in a powerful emotional effect. In story after story, these protagonists leave home knowing they can never return to their people—never again live in a place that conforms to their intuition, never again live in a place where they are an insider, where they truly belong. And it’s this, I think, that imbues these protagonists’ primary relationships in these stories—almost always with someone native to the culture they are embedded in—with such a luminous sense of meaning: the only homegoing possible for these characters lies in meaningful connection with strangers. They must find a way to truly make contact, to understand someone from a world that is foreign to them, and in so doing, advance the cause of a universal community.

It’s a theme that hit home for me, through lockdown and beyond, into this uncertain time in which we find ourselves, when the rules surrounding where we may go, and who we may come into contact with, and how, seem to be constantly shifting.

Because if one thing is certain, it’s this: We cannot go back to the world we inhabited before the pandemic. Not only because the threat the virus poses may never end, but because this time itself has changed us. We cannot return to the same point on the circle of our lives, only to the same point on the spiral.

_____________________________________________________________

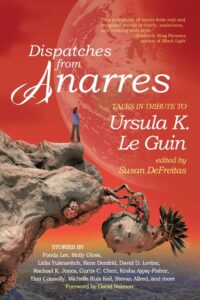

Dispatches from Anarres: Tales in Tribute to Ursula K. Le Guin, edited by Susan DeFreitas, is available now via Forest Avenue Press.

Susan DeFreitas

Susan DeFreitas is the author of the novel Hot Season, which won a Gold IPPY Award, and the editor of Dispatches from Anarres: Tales in Tribute to Ursula K. Le Guin. Her work has been featured in the Writer’s Chronicle, the Huffington Post, the Utne Reader, Story magazine, Daily Science Fiction, Oregon Humanities, and High Desert Journal, as well as other journals and anthologies. An American of Indo-Guyanese descent, she divides her time between Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Portland, Oregon, and has served as an independent editor and book coach since 2009.