The temperature in Stockholm fell to -10 degrees Celsius. In the morning, they wrapped the boy in a wool bodysuit, wool overalls, a sweater and a neck warmer, an organic alpaca wool onesie, thick knit socks and the big, yellow pom-pom hat that slipped over his eyes when they put him in the bunting bag in the stroller. The hat made him sleep. Then Anna pushed him through the towering snow. Down to the station, over the rocky hill, across the field, past Santa Fé and back home. After an hour her feet and hands were frozen and dead despite the many layers, and Aksel came down from the apartment and took over. Then Anna went upstairs and warmed up with a shower. When the boy and Aksel returned from their walk, she breastfed the child as agreed, kissed Aksel and went back out again, the same route, down to the station, over the rocky hill, across the field. It had started to snow again. As she stepped into Santa Fé, the cold swept through the open door and the few guests shivered in the corners, all of them with their coats still on; the room couldn’t heat up when the door opened so often. She ordered a liten latte and sat at her favorite table by the window facing the field. The air was still, the snow fell in fat flakes. She liked Stockholm for its snow. In Copenhagen it rarely snowed. She heaped sugar into her coffee, drank the sweet, lukewarm drink. It was half past noon, she lifted her black leather bag onto the table and pulled out a number of identical A4 folders, piling them in front of her. She watched the café’s clientele. An old man in a hat, a grandmother helping her grandchild onto a chair. The young girl who worked there was leaning against a table, checking her phone.

Anna had no education. She had attended a creative writing school for a few years and taken some classes at university without ever finishing.

Instead she had worked since she was very young. Anna thought about what she would do now, and how she would earn money. She thought about her previous jobs in order to glean what skills she had accumulated, and which principles she had been taught.

Not having any profession apart from motherhood made Anna consider what sorts of qualities defined her.

She was not a member of any union, and she had never held a permanent position. She joined an unemployment insurance fund for journalists when she realized she was pregnant so she could get maternity benefits.

Anna wasn’t poor. Her income fluctuated. Some years were fat years, others lean. Because she didn’t have a fixed salary but freelanced and wrote books and worked six-month gigs, it was hard for her to gauge her own finances.

There were periods of six or nine months when Anna would be quite well off, wealthy even, but then the curve dropped and she would have no income at all.

During the fat months, Anna couldn’t resist spending a lot of money, but at the back of her mind she feared she was living beyond her means and would soon be punished for it with a pile of bills she couldn’t pay.

But these unpayable bills had not yet managed to catch up to Anna, which led her to believe she was perhaps very rich and in fact lying to herself and everyone else about it.

In Sweden they lived off Aksel’s parental benefits and a grant Anna had received while she was pregnant. They had enough money to tide them over until sometime next year when they would move back to Denmark.

The first thing they did when they moved to the city was buy new clothes. It became their obsession. Everyone in Stockholm was well-dressed, and their clothes were always new. There was none of the shabby Berlin style they knew from Copenhagen. Here, you needed elegant garments made from understated, luxurious materials. A long, dark coat, black dress pants from Hope, a heavy, blue velvet jacket with pearly buttons from Our Legacy, crisp white shirts and platform shoes, matte lipstick and a stylish haircut, which was one of the most important status symbols in Stockholm. All Stockholmers were always slightly overaccessorized, Anna thought; the addition of a hat tipped the scales. It was ridiculous, but Anna and Aksel couldn’t help themselves; they spent all their money on new clothes at Brunogallerian on Götgatan and (on sale) at NK, the upscale department store on Hamngatan. Anna couldn’t think of anything to do besides shopping. Loneliness drove her to massive sprees. It became her language and preferred mode of expression. Shopping became an art form. The juxtaposition of materials in the shopping bag, orange corduroy paired with green-and-white beaded earrings, a fuzzy black angora sweater over a pair of blue slinky pants in a wool and silk blend. A bright-pink notebook made from recycled plastic bottles. A silver ring with an eye that wept a crystal tear.

The child woke up many times throughout the night, always with a whimper or a change in the rhythm of his breathing, prodding her awake a few seconds before him. She would lift him up and walk around until he settled down again, or pull him into her bed and feed him.

At night, Anna was a mother. At night, it could not be doubted. Aksel slept heavily and didn’t wake up. The child was hers. She was Anna, she breastfed in the dark. She held him in her listening, she coaxed him to sleep, she did so with a serenity, an acquired instinct. When his body grew heavy, she knew it was time to put him back down. If she put the child down too soon, he would cry, if she put him down too late, he would wake up confused and cry even harder. There were thirty seconds in which she could put him down, in which he would let sleep wash over him.

When the boy had fallen back asleep, Anna crept out to check the digital clock on the oven. Winter was dark and long, and she couldn’t guess the time by the light outside. From the kitchen Anna looked down at the snow on the road. The big plane tree was lit up by the streetlight below, each branch and twig doubled by a weightless layer of snow. She felt the snow in her mouth.

Almost as if he had sensed this bliss, Aksel decided that from then on he would take the boy when he woke up at night. This would, he believed, result in Anna getting more rest.

“You need to sleep.”

At night she always woke up before Aksel, who now lay closest to the boy. She climbed over his sleeping body, gave the boy his pacifier and caressed him until he fell back asleep. Sometimes he cried long enough for Aksel to wake up and take him, under the impression they had all woken up at the same time. Their both being up at night with the boy only deepened Anna’s sadness. The nights had been hers, like a remnant of her pregnancy where it had only been her and the child. She had no words for this experience and didn’t know how to explain to Aksel that in his attempt to protect her, he had only buried her deeper.

__________________________________

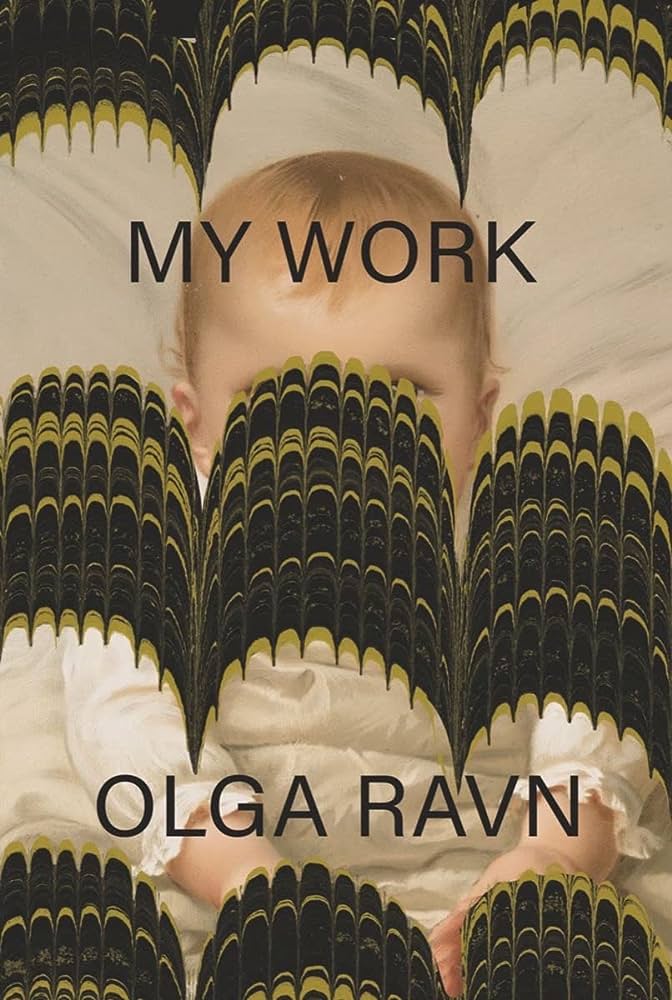

Excerpt from My Work by Olga Ravn, translated by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell. Copyright © 2020 by Olga Ravn. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp