My Own Private Genre: Literary Manhunt

On Novels of "Biographical Detection"

When I was 22 I started dating, as you do, a member of my undergraduate creative writing workshop. And despite all of their perils of dating a fellow writer—which are true and various and can be expounded upon elsewhere—I will say this: it has the advantage of letting you date another reader. This boyfriend and I were both voracious readers, but we had very little overlap in what we read—my favorite authors were 19th-century female novelists, if contemporary they were Canadians, South Asians, South Americans. His favorite authors were classic white male American titans from two decades before—Roth, Cheever, Carver, or contemporary short story writers I’d never heard of because I preferred novels.

It was illuminating—I recommend dating a reader if only to double your book-awareness, an important value. I’m unashamed to have strong opinions on books I’ve never read, because I followed along with the reading of the boyfriends I was dating at the time. (My relationships with non-readers never lasted very long—what do other couples talk about over beers?) When you date a reader you get to live vicariously through all the stages of reading a book—when they’re looking forward to a book and why, what they think after the first 50 pages, then midway, and how they felt about the ending. I’ve found some of the best payoff in long-term relationships when a book comes up that my partner read years ago, and they now have a different opinion I hadn’t known about. How could that be? I’d interrogate, as if my own views had never changed through differences of age and geography.

In these relationships, it’s thrilling to ask your partner what they’re reading next. And this particular boyfriend was embarking on a stretch of reading that fascinated me. It was for a class on “Biographical Detection in the Novel.” What did that mean, I pressed, probably abruptly putting down the Sierra Nevada I inevitably would order. They were all novels that followed a character investigating another character’s life, he said. I was struck by the concept. The possibilities seemed to be fascinating, and endless. I’d already graduated, but if I hadn’t I’m positive I would have enrolled in the class. As it was, the boyfriend and I broke up and I left for South America, and I never got to borrow the course books from him.

Over the years, however, I’ve kept my eye out for this set-up, adding to my reading here and there. To this day I get a thrill when I find a new book that fits the definition, or when a friend texts me out of the blue with a new title. It’s like having my own private favorite genre.

Like a detective novel, these books are characterized by a central mystery and the process of detection that leads to solving that mystery. The mystery, however, is not a crime—it’s a life. A person, usually only tangentially related to the subject (the latter is often deceased), becomes engrossed in the discovery of this person’s life, and in the best of the genre we also discover more about the detective’s self along the way. These narrators are never professional detectives; rather they are ordinary people, often writers, who self-consciously employ the tools of the detective’s trade.

Why these books are so good is simple—it’s much easier to get engrossed, as a reader, in a mystery or a quest. There’s an inherent narrative propulsion to these plots that got me through even some of the worst novels I read in MFA workshops (and they were therefore some of the worst novels I’ve ever read, since I had to read the whole things). But more than the novels with a straightforward mystery or a quest narrative, they let the author do the double trick of exploring two characters at once—making us think it’s about the person being investigated when it’s often really about the one doing the investigating.

But the novels of biographical detection have another coup—they essentially allow the author to write a character study while making us think we’re reading a thriller. The discovery of information in these novels is expertly paced, and how it’s received in the most interesting examples opens them up for formal experimentation—here is the space for letters, found texts, works of art that many of them employ.

Thanks to the magic of Google, it turns out I could find the syllabus to that long-ago class, no ex-boyfriend contact required. It was taught by a professor named Mitchell Breitwieser whose course description concludes:

The story of the investigator is as important as the story of the investigated: whence the interest? How does the investigation determine its own outcome? What does the investigation have to do with broader histories?

I’m most interested in this second question, of how the investigation determines it’s own outcome. So often in these books the investigator thinks he is his own independent actor, only to realize he’s been at the mercy of greater or more sinister forces the whole time. Not for nothing are the protagonists of these books often writers, and it’s no mystery why this genre appeals to authors, then, with all the potential for the plot double again as a metaphor for the creative process.

And now, a list of favorites:

The New York Trilogy, Paul Auster

The New York Trilogy, Paul Auster

The quintessential example of postmodern detective fiction, this book is made up of three novellas. While not totally true to our above definition (in several cases the investigation is assigned) the three novels all involve biographical detection and spin off into mind-blowing examinations of lives, morality, and most of all, writing itself.

Absalom, Absalom!, William Faulkner

Absalom, Absalom!, William Faulkner

In this novel the detective is Quentin, whose, ahem, interest in his family has more tragic consequences in The Sound and the Fury. The man detected is Stupen, who Quentin’s grandfather became involved with in the decades before the Civil War, and whose ruthless establishment of a failed dynasty in the town of Jefferson Quentin slowly unpeels.

The Quest for Corvo, A. J. A. Symons

The Quest for Corvo, A. J. A. Symons

This one is actually nonfiction, but you wouldn’t know it—I read at least half of it on the assumption it was a novel. It’s not, but it perhaps has the most fabulous (in several senses) subject of all of these books. A book by Baron von Corvo catches the attention of A.J.A. Symons and leads Symons on an eight-year biographical quest, pioneering modes of nonfiction writing along the way. Frederick Rolfe (Corvo’s real name) is his own worst enemy, betraying even those who try the most to help him, and the episodes of his life are hilarious until they become tragic. There’s a definite sub-strain of homophobia (Corvo was gay, Symons disapproved), but still a fascinating portrait of a writer navigating poverty, post-Oscar Wilde England, and the pursuit of an artistic life at all costs.

A Coffin for Dimitrios, Eric Ambler

A Coffin for Dimitrios, Eric Ambler

When I asked my dad if he’d read this one (he’s an avid mystery reader), he scoffed at me. Eric Ambler? he said—as if I’d asked if he’d noticed that California had a lot of freeways. Ok, ok, so apparently it’s a classic, but for good reason—it’s perfectly plotted, with twists, characters, historical traumas, settings in European dance hall/brothels, and fight scenes that would not be out of place in a James Bond movie (and the Daniel Craig reboot, natch).

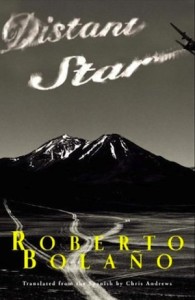

Distant Star, Roberto Bolaño

This was one of the final Bolaño books I read, but it instantly became a favorite. Essentially a novella-length cross between The Savage Detectives and Nazi Literature in the Americas, the biographical subject is Alberto Ruiz-Tagle, later Carlos Wieder, the member of a poetry workshop in Chile before the coup, a reserved boy who, one of his fellow students intuits, hasn’t truly found his own voice. Our narrator follows Wieder’s career in horror as he does find it—joining the army, sky writing, traveling to Antarctica, exploring photography, working on Italian porn—oh, and being a sociopathic serial killer supported by the Pinochet regime who does True Detective-worthy horrific things to women.

Nicola DeRobertis-Theye

Nicola DeRobertis-Theye was recently chosen as one of the Center for Fiction’s NYC Emerging Writers Fellows. She is a native of Oakland, California and has an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. Her work has appeared in AGNI and Treehouse Magazine.