My Own Personal Herakles

On Love, Loss, and the Fire at the Center of the Earth

I am molten matter returned from the core of earth to tell you interior things.

—Anne Carson, Autobiography of Red

By midnight, the air is swept through with sulfur. Athanasius Kircher, a 35-year-old Jesuit scholar, has chosen this hour because the lava will be easy to see, gleaming fissures marked in wide ribbons of liquid light. He’s chosen someone strong to hold the rope, a laborer that he describes later in his notebook as “an honest countryman, a true and skillful companion.” The two of them seem the only ones awake. Vesuvius sleeps, but restlessly; its snores send up gusts of smoke.

At the crater, Kircher loops the rope around his chest and waist. The ropes creak as he is lowered down, and he hangs there, like a spider on a strand of web, turning slowly in the updrafts. He looks down, past his feet, into the source of the rumblings, writing later of this moment, “I thought I beheld the habitation of Hell.”

When he’s had enough, he tugs thrice on the rope, and the “honest countryman” hauls him up, gasping. “It’s just as I thought,” he says when he can speak again. “It’s all the same fire.” Kircher has reached the conclusion that Earth contains a single central fire in its core that connects to the surface through volcanic conduits.

It is 1638, and Kircher is at work on his two-volume tome Mundus Subterraneus. In it he writes, “The whole earth is not solid but everywhere gaping and hollowed with empty rooms and spaces, and hidden burrows.” He describes how, deep beneath its surface, the earth holds great oceans of flame that are connected by intricate labyrinths and passageways.

He writes, “Volcanoes are nothing but the vent-holes, or breath-pipes of Nature.”

He writes, “Volcanoes . . . do sufficiently demonstrate [Earth] to be full of invisible and underground fires. For wherever there is a volcano, there also is a . . . storehouse of fire under it. And these fires argue for deeper treasuries and storehouses of fire, in the very heart and inward bowels of the Earth.”

Kircher believed this because he’d dangled above the heat, breathed it in and probably concluded that this fire was every fire. And later, if challenged, he might’ve told a skeptic, “But I saw it. I was there.”

*

How does distance look?

—Autobiography of Red

As a child, I once spent an afternoon sleeping atop a bookshelf, a single blanket across me. I climbed drowsily up to that narrow height, wanting even sleep to become dangerous, and my mother later opened the bedroom door a crack to see me perched, sleeping soundly on that verge, dreaming of canyons, craters, flight, and falling.

I thought of this years later as I drove west, 16 hours between me and the coast, between the continent’s edge, this shelf over which it seemed I could drop as easily as turning in my sleep. Crossing the California border—Mount Shasta swallowing the skyline and never seeming any closer even after hours of approach—I started to see all these signs along the highway that said Volcanic Legacy. Scientists now describe Mount Shasta as a “potentially active” volcano, although it hasn’t made a real peep in centuries. Still, it is the potential that keeps scientists watching, keeps me mindful of what this valley may have looked like coated in a thick layer of liquid flame. As I drove, those green-and-white signs marked proximity to this giant that slept at a distance, speaking softly of its days of wakefulness.

I undertook the drive not merely to reach a destination (my sister, her terrier, her apartment well-stocked with beer and leftover Easter candy) but also for the act of driving itself. At the time, I didn’t like flying because the miles slipped through me too easily up there. I preferred to earn distance, the odometer ticking off space. As I dipped southward, Mount Shasta behind me, I felt I was fleeing as much as arriving. I’d been holding, for months, onto a longing that would not move either forward or away. It sat in my chest like cooling lava, hardening in my limbs.

I’d gone to see a doctor because I couldn’t sleep, because my sleep was so full of the shape and smell of someone I couldn’t seem to rid myself of. The doctor gave me pills and asked, “Do you think you can move on?” I wasn’t sure I could move. I told him, “I don’t know.” But. I got in the car, started to drive, the dormant volcano ahead and then behind, a blue-and-white triangle in my rearview mirror.

*

Everyone seems to be waiting, said Geryon. Waiting for what ? said Ancash.

Yes waiting for what, said Geryon.

—Autobiography of Red

Other things that are “potentially active”: unhatched eggs, the cassette tape before it is played or rewound, the switched-off headlights of a moving car, an unmoving car, a sleeping dog, a slack sail, any item that gets lost in the mail, storm clouds, Band-Aids, milkweed, Christmas decorations, stamps, envelopes, frozen food, frozen anything, paint, rope, unpoured cement. Also: everyone. Every single person that you touch or encounter.

*

Motion

was a memory he could not recover

—Autobiography of Red

The car is a great space for longing. Especially if the object of longing is absent. Why? Because the car moves. Because, in a car, I am constantly entering new space, the light changing as I pass through it. Because there is only one direction to move in—a line that curves or wavers but is still forward motion.

As wide-eyed as I was after 16 hours, I drove straight through the night because when I called around to hotels in rural Oregon at three in the morning, the receptionists kept saying the same thing: there is a horse show in town this weekend, and all the hotels are booked. Booked solid. And so—caffeine and protein bars and oranges peeled while steering with my knees and more cigarettes than any lifetime needs. And a Bonnie Prince Billy song on the radio that goes

And love will protect you

To the edge of the wood

Then a monster will get you

And love does no good.

And it couldn’t be any other way. Because the hotels are full of horse lovers. Because, in my backpack, books of poems about this very experience. Because my sister settled in a town far away from me, and I am going to see her, to lie on clean carpets with her little dog and hear her voice in the kitchen saying, “I know what you mean, jelly bean,” and feel the heat leaving my arms and chest in a slow leak.

Because, the semis creak and groan like giant cattle as I pass them, and it will be a sound I recognize as something ancient, something like lava leaving the earth by any means possible. And because, as dawn lifts and pushes darkness away from itself, I will see a volcano covered in snow and really believe for the first time since setting out that this longing, this specific one, will end, and I will somehow be better for it.

*

Whenever any creature is moved to reach out for what it desires, Aristotle says, that movement begins in an act of the imagination.

—Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet

The world has openings. Kircher knew this, believed that the earth’s core contained spaces for interior flight. Mundus Subterraneus contains diagrams of dragons, winged and spitting flame. Some creatures, he maintains, belong only to the “lower world.”

In Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red, the winged monster, Geryon, flies into a volcano and survives. He flies in search of a connection with the basic forces that make love tangible. He flies in order to better understand the splendor and agony of what he feels for his beloved, Herakles. He flies to put longing into action, to embrace his nature as desirer.

This book made the 16-hour journey with me, and upon my arrival, I sat in my sister’s backyard breathing smoke, the book in my hands smelling like a damp map, whispering advice to Geryon as if he were a character in a soap opera. “Come on, dude, is he really worth all this?”

In this novel-in-verse, the plunge into the volcano is the only time we see Geryon in flight. It is the only time we lose sight of him. It is the only time we as readers feel lost. And it is a good feeling. It is the feeling of watching ourselves reach for something, desire it, and emerge from the reaching, somehow still intact.

*

A volcano is not a mountain like others.

—Autobiography of Red

Today, I spent the afternoon reading about volcanoes, about the French painter who moved to Naples in 1764, set up his easel at the foot of the erupting Vesuvius, and didn’t move for a year. His name was Pierre-Jacques Volaire, and he was one of the few painters of the time who went on-site to capture the eruption, who let the ash settle in his hair, mingle with the paint as it bled brightly on the canvas. His paintings show figures in silhouette, celebrants who climbed the slopes. The heat touches their foreheads, the lava churning at their feet, and they look away from the viewer, toward the space of smoke and liquid flame.

In the painting The Eruption of Vesuvius, (1771), which belongs to the Chicago Art Institute, six human figures are visible, tiny, a great distance from the viewpoint. One figure helps his companion climb a steep slope. A group of three stand slightly apart, one figure appearing to rest his hand on the shoulder of another while the third is seated jauntily on a boulder. The sixth figure is alone, resting on a high ledge, taking a moment to gather his breath while he gazes across the distance, the heat touching every part of him. An air of celebration animates every figure except this one, who appears slightly slumped and serious. I like to imagine that this is a self-portrait of the artist in miniature, that Volaire has incorporated himself into the painting, describing with dark shading the solitude he feels while he sits all day mixing colors and watching the lava change shape. I like to imagine, also, that it is me.

*

He understood that people need

acts of attention from one another, does it really matter which acts?

—Autobiography of Red

In Eros the Bittersweet, Anne Carson explores the triangle by closely examining a fragment by Sappho, in which the poet watches from a distance while her beloved interacts with a beautiful man and laughs at his jokes. In her observation of the far-off couple, Sappho feels “fire . . . racing under skin.” Carson says of this fragment, “It is not a poem about the three of them as individuals, but about the geometrical figure formed by their perception of one another, and the gaps in that perception. It is an image of the distances between them.”

Volaire’s painting is full of triangles: the volcano itself, the loose triangle of cloud framing the moon, and, of course, the triangle formed by the placement of the three separate groupings of tiny figures—the pair at the right, the central trio, and the solitary figure at the left.

This lone sixth figure seems invisible to all the others, slightly above and to the side. It is his close proximity to them, separated by a mere inch on the canvas, that makes him appear so isolated. He is the only figure who isn’t gazing up at the volcano, and this unwillingness to participate in the wonder that the others are experiencing places a lonely, flame-edged nimbus around him.

Carson goes on to say of Sappho’s fragment:

It is a poem about the lover’s mind in the act of constructing desire for itself. . . . But the ruse of the triangle is not a trivial mental maneuver. We see in it the radical constitution of desire. For, where eros is lack, its activation calls for three structural components—lover, beloved, and that which comes between them.

In The Eruption of Vesuvius, the isolated figure, by directing his gaze away from the volcano, seems to reach simultaneously for the viewer, the painter behind his easel, and the trio who lean together and perhaps speak of the lava’s path. The trio seems active, each in a state of arrested motion, gesturing toward the fire belching into the space above them. But this lone figure seems unable to engage with the spectacle, satisfied instead to feel its heat on the side of his face. We, as viewers, have no clear idea of his desires, but they seem to be human rather than volcanic.

Desire can make us ignore the volcano, the vast geometrical figure that looms behind us spitting fire, itself a triangulation of flame, stone, and vapor . . . or of danger, science, and celebration . . . or of love, loss, and longing . . . or of, simply, three lines of distance. Whatever the case may be, desire can make us lose sight of all the symbols of desire itself.

*

The reach of desire is defined in action: beautiful (in its object), foiled (in its attempt), endless (in time).

—Eros the Bittersweet

After Geryon returns from his flight into the volcano, he reflects that “We are amazing beings . . . . We are neighbors of fire.”

Geryon’s flight serves as an enactment of his desire to be fully consumed by his love for Herakles. Afterward, he seems to think that, although we are “amazing beings,” we can never manage to exist immersed in pure longing, amidst fire itself, but rather, we exist adjacent to flame, to the volcano. He concludes, “We are neighbors of fire.”

The moment of Geryon’s culminating flight and epiphany about the nature of his longing for Herakles returns readers to an understanding of desire as an unsustainable state of being. Desire is as transient as a breath of flame. Or a flight into a volcano. The epiphanies that such a flight reveal may seem permanent, but it is just as impossible to live within a constant state of epiphany as to live inside a volcano.

In Autobiography of Red, fire is again and again depicted as a force that cleanses and reveals, although the reveal in the final scene seems to be that we can no more possess the object of our desire than hold raw flame in our hands. But we can “stare at the hole of fire” as Geryon does. We can call it beautiful. We can address ourselves “to the moment while Eros glances into your life and . . . grasp what is happening in your soul at that moment” and “begin to understand how to live” as Carson herself urges in Eros the Bittersweet. We can be neighbors of fire.

*

How people get power over one another, this mystery.

—Autobiography of Red

Geryon had his Herakles. I had mine. About him I will tell you: he was child-eyed, green around his edges. He told stories about his father inventing useless machines in his garage. He was afraid of flying and of ladders. He once spilled a bag of pistachios across his floor and just left them there, crunching underfoot, for weeks. He liked to show people a photograph of himself as a child wearing a football helmet. He thrived during long drives and prided himself on how neatly he could piss into empty soda bottles amid traffic. His car smelled always like fried-fish sandwiches and feet and cigarettes. He was clumsy and strong and tried to do justice to the things he loved, which included primarily: writing and basketball. He was a smoker like me, and when I tried quitting for two months over the winter, we used to stand outside of bars, and he’d exhale long silky plumes of smoke into my face. When I shared this detail with my sister, she said, “That is some shamanistic shit,” and, “You got some bad juju, Bun. I tell you what.” My sister, although two-thirds of the way to becoming a doctor, believes very insistently in the magic of things.

But what else can I tell you about him? Maybe the only thing that matters: he did not want what I offered him.

*

This would be hard

for you if you were weak but you’re not weak.

—Autobiography of Red

I was alone in Iowa City three years back. I’d just broken up with my boyfriend, Jon, and my friends had all moved east. I found myself watching, over and over, Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli on the tiny TV perched above my fireplace. The story features Ingrid Bergman as Karin, a frantically anxious Lithuanian refugee who, in the aftermath of World War II, gains her release from an Italian internment camp by agreeing to marry a recently freed prisoner of war and fisherman named Antonio. They meet at the camp on opposite sides of the fence, passing cigarettes back and forth through the barbed wire. She doesn’t speak much Italian but understands just enough for Antonio to make clear that he is offering her a life of consistent magic on the tiny volcanic island of Stromboli, his homeland, the place of his birth and upbringing.

Arriving there, Karin sees that the island is actually barren and hideous and plagued by sulfuric fumes that leak toward the sea, settling in the still air of the village streets. The locals are suspicious and unfriendly; Antonio demanding and smothering. We watch her become increasingly trapped and isolated, terrified by the life she’s found herself mired in.

In the film’s final scene, Karin tries to escape the island by crossing the volcano on foot, desperate, breathing the evil-smelling heat, choking into a handkerchief and moaning. The smoke surrounds and overwhelms her, and the smoke is genuine. Filming took place on the slopes of an actual volcano, and so when we hear Bergman coughing and gasping for breath, her gasping is real.

The volcano rumbles a little but is mostly silent until she arrives at the crater, where she stops, gazing into it as it belches smoke. She covers her face with her hands and begins uttering nonsensical fragments: “No. I can’t go back. I can’t. They are horrible. It was all horrible. They don’t know what they’re doing. I am even worse.” She pleads dramatically, “God, my God. Help me. Give me the strength. The understanding and the courage. Oh my God. My merciful God . . .”

All I’d known about the film before watching it was based solely on a cheery little ditty by Woody Guthrie that I used to sing while doing the dishes:

Ingrid Bergman, you’re so perty.

You’d make any mountain quiver.

You’d make my fire fly from the crater.

Ingrid Bergman.

But the song is thematically similar to the film in that both are about desire divorced from intimacy—about seeing something or someone that you want and admiring them from afar, whether from the other side of the barbed wire or from a seat in the movie theater.

The reality: the volcano doesn’t submit to any of us, even Ingrid Bergman herself; it must be endured, crossed on foot while we weep and grope blindly. We must be alone with the struggle. We must learn to come to terms with our desires, live with their consequences, fly headfirst, wings spread, into the gaping crater. Like Geryon. Like Ingrid Bergman. Like me that summer in Iowa when I sat in a damp backyard, thick with gnats, and told Jon that the life I wanted wasn’t a life with him. I remember the whole time I talked I swatted angrily at the gnats, batted at them, while he sat, defeated, and let them settle on his face, sip his sweat, and crawl across the red expanse of his forehead.

Three years later, I sat in a car that smelled of fried-fish sandwiches and feet and cigarettes and told the man sitting in the driver’s seat what it was I wanted, asked him what he thought love was supposed to look like, and he’d said, “When you love someone, it should hurt every time you see that person.” This was the only definition he ever offered me. I accepted it, coughing from the cigarette smoke and choking just as Ingrid Bergman had, trying to complete a journey that stops at the crater’s edge.

This old mountain it’s been waiting

All its life for you to work it.

For your hand to touch its hard rock.

Ingrid Bergman, Ingrid Bergman.

We come close, move apart like the bassa danza, the dance that Carson refers to in Eros the Bittersweet, popular in Italy during the first half of the 15th century. In the dance, three men and three women change partners repeatedly and “each man goes through a stage of standing by himself apart from the others.” And so—in order for the weight of desire to take form, we must stand (or sit, or slump) in a space of solitude, whether crawling across the volcano’s face, or leaning against a rock at its foot; in a film, in a painting, in a backyard, in a car.

*

We have to keep going back to [the moment when we understood], after all, if we wish to maintain contact with the possible.

—Eros the Bittersweet

In the spring of 1638, Athanasius Kircher bobbed among earthquake-stirred waves in a little sailboat and watched Stromboli “throwing up huge billows of smoke” at a distance. The crew of the little boat was scurrying back to the mainland, the ash from the eruption reaching across the water to make their eyes stream, their hair reek of sulfur afterward. Kircher wrote later that it is di≈cult to witness an eruption without feeling that “the cracking of the earth . . . insinuate[s a] complete, fatal and funereal destruction.” He went on to say, “You would have said that at that very moment the day of final judgment was looming.”

But it wasn’t. The boat returned safely to harbor. Kircher may have even allowed himself a glass of wine with dinner that evening, celebrating survival. Meanwhile, Stromboli erupted. Aetna erupted. Vesuvius smoked and trembled. And Kircher decided he needed a closer look. He made plans to enter Vesuvius’s crater.

Kircher wrote in his notebook, “I had a great desire to know whether Vesuvius also had not some secret commerce and correspondence with Stromboli.”

This is a desire Kircher and I share.

*

He had a respect for facts maybe this was one.

—Autobiography of Red

Things I’ve learned about the series of Vesuvius eruptions that took place between 1764–94:

1. In 1764, a priest lived at the foot of Vesuvius, and he went every single day to record the volcano’s activity in a little book. He threw stones into the lava, but they didn’t They moved with the lava down to the sea, like a bird landing on a horse’s head. The priest saw whole trees walking upright while they burned. He saw the lava touch a wall, and the wall surrender into dust and mortar with a small, leaning breath.

2. Naples was referred to at the time as “a paradise inhabited by devils.”

3. It became fashionable during that period for the rich to build their villas on the southern slopes of Vesuvius, the area most vulnerable to volcanic attack.

4. Parties of scientists, including one with the young Michael Faraday, would scale the face of the volcano to gather lava samples, sometimes spending the night on the cooling lava beds. “The courage of these early scientists was extraordinary and unnerving,” says James Hamilton in his study Volcano. “So cool were they that [one] party fried eggs on a piece of lava, ate a hearty lunch and sang ‘God Save the King’ as earthquakes made the mountain shake like jelly.”

5. During that 30-year period, Hamilton says, all of Europe was blessed with “extraordinarily vivid ”

*

Facts are bigger in the dark.

—Autobiography of Red

Parallels:

1. On the first night I met my Herakles, he told me a story about trees walking.

2. He and I used to refer to the town where we met as “the valley of the shadow of weirdos.”

3. He once had his apartment broken into, while I continued to keep my door unlocked. Always.

4. On Halloween, he drove me home, and we sat in my driveway eating pizza. I invited him to come inside, and in response he turned up the radio, the Beach Boys drowning me out with “I may not always love you / But as long as there are stars above you . . .” Getting out of the car, drunk and feeling dramatic, I yelled over the music, “You make me lonelier than anyone I’ve ever met.”

5. He cared nothing for sunsets, but once we were standing on a sidewalk outside a bar, the sky seeping color through purple gashes, and he said, “What do you think it would be like to be a painter?”

*

We would think ourselves continuous with the world if we did not have moods. It is state-of-mind that discloses to us . . . that we are beings who have been thrown into something else.”

—Autobiography of Red

On the drive to California, I moved steadily through a darkness that had no moments of color, even with the force of my headlights. I listened to a Bonnie Prince Billy song that ends with the lines “And even if love were not what I wanted / Love would make love the thing most desired.” And then—a sudden and terrible silence. I drove without caution through nowhere places where the road curled up against itself as if trying to get warm. I stopped by the side of the road and peed next to the car, hoping, in the densest hours of pre-morning, that no car would round the bend to see me crouching, small and gargoyled and blinking into headlights. Squatting, I could hear the rush of water beside the road to my right, but I couldn’t see the river. I hummed to myself while peeing: “Even if love were not what I wanted . . .” The stars were close, moving hugely within their spheres, fixed points of motion.

Carson speaks in Eros the Bittersweet of the “blind point,” and maybe she was writing about me crouching next to my car when she wrote,

Arrest occurs at a point of incontinuity between the actual and the possible, a blind point where the reality of what we are disappears into the possibility of what we could be if we were other than we are. But we are not. . . . We are not lovers who can both feel and attain their desires.

Maybe she was talking about Volaire’s painting, the figure who cannot quite bring himself to merely peer over his left shoulder at the erupting volcano, who, rather, gazes off into the whirring distance of the Gulf of Naples, in profile to the artist, the viewer, to me as I stood in the Art Institute chewing on my thumb and not noticing him, noticing instead the spectacle, the sublime eruption, that floods the canvas with fluid orange light. It looked as if the paint were still wet.

Maybe Carson was writing about the moment when Herakles stood with me in a backyard, telling me about his grandfather weeping at a kitchen table on the day that Elvis died, and I saw, in the night sky behind him, a shooting star streak wildly, falling toward its own end, and I cried out, pointing to the space of sky now emptied. He turned, looked, but it was too late.

This is the blindness that doesn’t choose you, that settles on you like snow, like ash.

*

Does Eros have wings? Does Eros need wings? Does Eros cause others to have or to need wings? Does Eros need to cause others to have wings? Does Eros need to cause others to need to have wings?

—Eros the Bittersweet

A letter from me to Geryon:

Dear friend,

You want to believe we are neighbors of fire, and so you, like so many of us, get as close as you can. I am learning about volcanos, Geryon. I am learning about the temperatures of lava (as hot as 1,200 degrees Celsius), about the age of the earth’s insides and the fact that underneath, the world is still forming. I am learning that the plates of the earth move at a speed of four centimeters per year, which, incidentally, is the same speed at which fingernails grow. I am learning that you cannot hold the world in your arms, but the desire to do so is what keeps us moving. I know you know what I mean. I know you know that if a man (or a woman, or a monster) is winged, and if he is lucky, he can fly straight into the heart of the world and look around for a minute before passing out from the heat. I know you know what you meant when you thought, “We are amazing beings.” We are. I confess I am a little envious that, like Athanasius Kircher, you are able to say with confidence, “Surely this fire is every fire,” are able to say, “I saw it. I was there.”

All my love,

Renée

P.S. I wonder if you’ve seen the film Stromboli. I think you would like it.

*

I once loved you, now I don’t know you at all.

—Autobiography of Red

A letter from me to my Herakles:

Dear friend,

When I told you I was writing about volcanoes, you said, “Of course.” Which made me feel known somehow, but also: is it really a comfort to be predictable? Once, after reading an essay of mine, you said, “Why aren’t I in this?” Well here you are. I will think always of you this way: breathing smoke into the air and then me breathing the air.

When I reminded you about that time a shooting star moved just behind your left shoulder, that time you turned to look a millisecond too late, you said, “Are you sure that was me?” Yes, I’m sure. We were both on drugs at the time, but my memory is especially sharp when it concerns you. It can be useful to remember how quickly things move and shift, lone star trailing dead behind you. From the start you were always elsewhere, long stride walking in step, bending forward a little onto porch steps. I watched while you drifted—like bad history, like the tree that walks on lava, like the sore tooth you can’t keep your tongue from probing. This remains true: I have never been crueler to anyone than I’ve been to myself. “I like moments in stories,” you once said, “when a character realizes they’re not okay.” What if, I wanted to say then, the realization happens and it changes nothing? This too remains true: I hope you’re okay.

All my love,

Renée

*

His eyes ached from the effort of trying to see everything without looking at it.

—Autobiography of Red

I recently attended a lecture about volcanoes, and the speaker, a man who’s devoted his entire life to the study of volcanism, kept referring to Vesuvius as “she.”

He stood at the podium and told the audience that volcanoes cause diamonds to form. Deep beneath the mantle, pipes will develop where pressure is so high that carbon rearranges itself into diamonds.

He told us that in 1902, Mount Pelée on the island of Martinique erupted, killing every single person in the city of Saint Pierre except for one lone survivor, the only prisoner in the underground holding cell of a jailhouse.

I don’t know what to do with all this. I want to get as close as I can to the belief that Kircher carried—that all the earth’s fires reach across great distances for one another, that we can survive even the closest brush with that central fire, can hover above it and “argue deeper treasuries and storehouses of fire, in the very heart and inward bowels of the Earth.”

I want to believe that after the plunge into the crater, the space created by longing will leave you open to other loves, loves even more generous and consuming than the one that brought you there; that afterward, a space remains where you can measure, triangulate, and find that there is just enough in you, just enough flame rising to the surface, to form something both permanent and gracious.

*

New Ending.

All over the world the beautiful red breezes went on blowing hand in hand.

—Autobiography of Red

Unable to stop for the night, I kept on. The smell of the road seemed like it would never leave me again; my legs shook a little, and I reeked from sitting for hours. The stars seemed to chase me, lifting their fruit to my mouth. I pushed forward, punched through the darkness into morning. Along the highway, men (and maybe women, maybe monsters) slept in the cabs of their trucks—their bodies tucked inside separate spaces, motionless, at rest. And separate from all of them, I moved—a comet streaming flame, steady in swiftness—gnawing at the uneven corner of a fingernail.

Things have to first occur to us before they can become action. We have to first desire motion before motion is possible. In the meantime, we can wait, wait for desire to shift. I recently discovered that the word ecstasy means “to be beside yourself” or “to stand beside yourself.”

And so: I stand and stand and stand. It’s all I can do.

When I finally pushed into California, the sun was fresh and full, and Mount Shasta cut its shadow firmly across every part of me. As I rounded a curve at 60 miles per hour, I startled a huge eagle who was feeding on a freshly killed rabbit. I slowed down, and the eagle flew alongside me for the distance of a few yards, peering in at me, curious and angry.

Maybe this is all I really believe: we are winged and we are lucky.

__________________________________

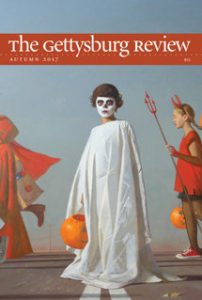

This essay originally appears in the Autumn 2017 issue of The Gettysburg Review.

Renée Branum

Renée Branum has an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from the University of Montana and an MFA in Fiction from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop where she was a Truman Capote Fellow. Her work has appeared in The Georgia Review, Narrative Magazine, The Gettysburg Review, Brevity, Alaska Quarterly Review, and Best American Nonrequired Reading, among others. She was a recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Prose Fellowship in 2020. She currently lives in Cincinnati, where she is pursuing a PhD in Fiction. Defenestrate is her first book.