My Mother Will Live Forever in the Stories of Alice Munro

Jonny Diamond on the Timeless Genius of Canada’s Greatest Writer

I came relatively late to Alice Munro.

Despite being a bookish Canadian with pretensions of being a writer, I resisted invitations and entreatments alike to read anything by—so I was told—our version of Chekhov. The reason for this reluctance is not complicated, and is frankly embarrassing in retrospect: Alice Munro was my mother’s favorite writer.

In what amounted to something more like petulance than twentysomething rebellion, I rejected Alice Munro along with the Margarets, Atwood and Laurence, and Carol Shields, a remarkable quartet of writers born within a decade of one another, all of them beloved of my mother (b. 1934). But it was Munro (b. 1931) who usually rose to the top of her bedside book pile, to whom she returned again and again.

Twenty-five years on, and over a decade since my mother died, it’s not hard to see why Munro was her favorite: born a few years apart they both married young, aged 21, and immediately set to the primary task of the 1950s housewife, the growth and care of a family (four children for Munro, five for my mother).

As the cultural and political upheaval of the 1960s played in hazy background projection across long years of diapers and laundry and unmade beds, both Munro and my mother wrote: the former, the stories that would become her first collection, Dance of the Happy Shades, a book that would inaugurate the quiet genius of our greatest storyteller of life as it is (as it lived by all of us, whether we like it or not); the latter, fragments of poetry and diaristic reflection that would only be read by her youngest son the year after she died, in a dusty overheated apartment in the ludicrously named Georgian Court Arms, a shabby, low-slung complex an hour outside of Toronto.

She wrote for everyone who has let the sharp edge of regret dull into a daily ache, who has been surprised by love, by need, by the desire for more.

And then the 1970s: Munro divorced her first husband (1972) and my mother left hers (1974); both found the men they would love for the rest of their lives. Unlike Munro, however, my mother would have one last child, at 42: me.

At this point you might be wondering if I am actually comparing my mother, Margery Bird, to one of the greatest writers to ever live and… yes, I guess I am. Insofar as they had something like the same life—at least up until Munro’s career took off—my mother, and her sisters, and their husbands, and their friends, were all characters in an Alice Munro story, just as Munro herself was.

And though this has nothing to do with her particular gifts as a writer, it is hard not to think of myself as a minor Alice Munro character, the accidental child of an unlikely love affair who finally and terminally thwarts the artistic aspirations of a woman too long defined by motherhood and little else, who finds briefly in the second wave feminism of the 1970s a recipe for independence, only to relinquish it once again to the duties of child-rearing.

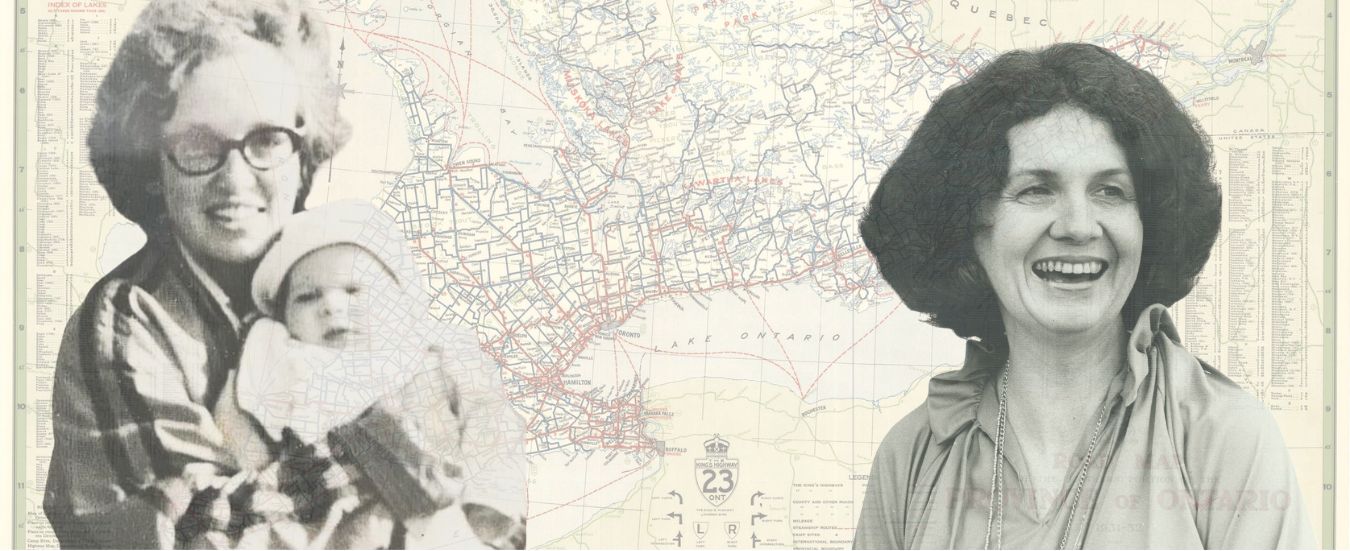

The author, with his mother, southern Ontario, spring 1976.

The author, with his mother, southern Ontario, spring 1976.

When I finally came to the stories of Munro in my late twenties, at that age when regret starts to harden into resignation, it felt like I’d been given a window into the inner lives of my parents: the countless dinner parties and lakeside BBQs I’d wandered through as a child, jumping onto beds covered in strangers’ coats, burrowing into all those mysterious scents—of motor oil and lilac and rye and so much cigarette smoke—blithely unaware of the tectonic roil of need just under the surface, each grown-up life a warren of wrong-turns and second chances, of closely guarded hope and bitter defeat.

Alice Munro saw it all. And it doesn’t matter if you’ve never eaten nanaimo bars sitting on the shag carpet at a Grey Cup Party, or carried a pitcher of beer to a table of tipsy grown-ups at a bonspiel, rink rafters thick with cigarette smoke; just as one need not have felt the summer sun fading on a dacha five-days ride from St. Petersburg to metabolize the truths of Chekhov (to whom she is rightly compared) one need not ever have set foot in Canada to understand Munro.

Because she wrote for all of us, everywhere.

She wrote for everyone who has let the sharp edge of regret dull into a daily ache, who has been surprised by love, by need, by the desire for more, who has hesitated and lost, who has kept going, kept wondering, kept feeling, so deeply and so quietly, through all the endless days that take us from one end of life to the other.

Alice Munro and my mother, Margery Bird, died in the same small town, twelve years apart. Port Hope is an otherwise inconsequential place set hard between the Trans-Canada Highway and the northern shore of Lake Ontario, forgettable in its sameness to a thousand other Canadian towns. Or at least that’s what I used to think.

To read Alice Munro is to see the life in each of these places, and in places like them, for what it is: forever brimming with too much, forever aching with not enough. We are all characters in an Alice Munro story, at the mercy of the relentless tidal pulls of yearning and regret only she seemed able to chart. I will grow old and die, and my memories of my mother will wink out and be gone. But her life will be there still, somewhere, in the stories of Alice Munro. Forever.

Jonny Diamond

Jonny Diamond is the Editor in Chief of Literary Hub. He lives in the foothills of the Catskill Mountains with his wife and two sons, and is currently writing a cultural history of the axe for W.W. Norton. @JonnyDiamond, JonnyDiamond.me