I was frozen solid in the bucket seat of my mother’s Impala. It was summer, a Wednesday afternoon in the year 1979, and I was eight years old.

“What the hell is wrong with this drivah?”

My mother honked her horn. She was short and had to rig her seat so she was practically bumping up against the steering wheel. She honked the horn again. “Come on, jerk!”

We were driving down the Prospect Expressway toward The City to see a play called Sweeney Todd. I’d seen the commercial on television—thirty wildly persuasive seconds of Angela Lansbury jouncing around with a funny hairdo and a bunch of people screaming for pie—and begged her to take me. She’d taken me to my first Broadway musical for my fifth birthday, and after that it became a regular thing. We’d get discount tickets at the TKTS booth for whatever was on that day—usually tourist-baiting stuff, people tap-dancing and singing about chasing the blues away or doing the hanky-panky. I loved seeing Gregory Hines tap dance, and Ann Miller canter across the stage of the Mark Hellinger Theatre in a cherry-red-spangled girdle. I loved the booming sounds of the orchestras. I sobbed uncontrollably at the ending of The Wiz. I was enamored of intensity and greatness, and I ached to be in Manhattan.

I cracked the window open a peek.

“Roll that window back. Aren’t you hot?”

“No, I’m freezing!”

“It’s so muggy out.” My mother held her cigarette limply with the tips of her fingers so it tilted slightly downward. Every so often she would flick it into the ashtray. She’d spent the whole morning blow-drying her hair into a series of au courant flips and folds that were now dismantled by the blast of air conditioning, but she still looked beautiful. She was 43 but looked a decade younger. “I can’t take this heat,” she said before taking a drag.

I took after my mother. I was strangely epicurean from a young age: I could eat atmosphere.When I was small, my mother was my ambassador to the outside world. She tried to bring me up as cultured—even if she didn’t know what culture was, exactly. In some respect, she liked the idea of culture the more she was deprived of it: attrition lent it a mystique. She dropped out of high school at 16 to marry my father and have kids, but always felt a lingering sense she’d missed out on something, some vital part of the world. She called this thing Culture, and it became a North Star for her, a guiding notion for what life could offer.

My father didn’t care for her formless acquisitions of culture and art. He resented her for wanting to eat at nice restaurants, ceremonies he thought absurd. “You can’t eat atmosphere,” he’d admonish. “I can,” she’d rejoin, momentarily possessed by a sudden imperial calm.

I took after my mother in this way. I was strangely epicurean from a young age: I could eat atmosphere. My father never took me on his fishing trips from Sheepshead Bay with my older brothers but I was glad. I hated the green murk and stink of oceans. Nature affronted me; I wanted culture. But I had the same problem as my mother: I didn’t know what culture was, and I never sought clarification. Asking questions felt like a breach of etiquette and I wanted to have good manners.

Together, we wandered the halls of museums, the lobbies of fancy hotels. With her last pennies my mother took me to voguish restaurants uptown, places like Sign of the Dove and the Quilted Giraffe. As we sat in beautiful straw-backed chairs sharing a meager pasta dish (she couldn’t afford two entrées) I felt lifted above my station, away from the hoi polloi, a citizen of the world. Other times, culture bestowed a different sort of gift. Near the entrance to the Met was a statue of Perseus displaying the beige disembodied head of Medusa, writhing with snakes. Seeing it for the first time—I was no older than six or seven—I felt something stir awake in me, something that felt like a soul or a spirit. The statue was strange and frightening, but I knew it meant something. I knew there was a reason it was being displayed in this magisterial palace of art, even if my powers of discernment were too puny to figure out why. Why did people paint these paintings, and sculpt statues from beige blocks of marble? Were they depicting something about life and the world? Was it a kind of reality? An escape from reality?

“Medusa,” said my mother somewhat approvingly after checking the title. “From mythology.” I knew mythology was a kind of history, a momentous doctrine—was that history mine? She took my hand and ushered me through atriums lit with skylights leading to rooms and tranquil hallways that led to adjoining rooms and tranquil hallways. We glided from marvel to marvel, past pagan images of gods and thunderbolts, cherubim and angels weeping for humanity. As a child I had a tendency toward the occult—I believed museums were repositories of sacred holy things. I developed an almost worshipful craving for anything urban, which I associated with God.

Each time my mother drove us down the Prospect Expressway I could feel my tiny fishbowl existence begin to open and expand. My excitement manifested as sickness: a queasy feeling of dread, like my insides were being spun through a centrifuge. Impressed by my sensitivity, my mother broadcast aloud her affirmation at each phase of my mounting anxiety, charting it as if monitoring an EKG: “Your face is all flushed.” “You’re excited, huh.” “You love The City, don’t you!” If my anxiety was pitched too high she’d warn that I was getting “overstimulated,” a word she used a lot. I couldn’t tell if being overstimulated was a good or a bad thing, just as I couldn’t distinguish between excitement and dread: I was still learning to map physical sensations. Everything was foreign to me, even my own intimate life.

__________________________________

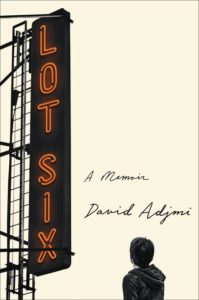

Excerpted from Lot Six: A Memoir by David Adjmi. Copyright © 2020. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Harper.