My Lessons From a Crash Course in Ghostwriting

Lauren Kate on How She Got a Degree in Pseudonyms

During drop/add the fall of my freshman year of college, the Intro to Poli Sci class my parents thought I should take was full, and I landed in my first Creative Writing seminar. More specifically, I landed at a conference table next to Jim. By way of an introduction, he held up his most recent book. I was amazed to be in the midst of an actual novelist, to see that he drank vending machine cranberry juice, had freckles on his forehead, and breathed the same air as me.

My love of novels had always been ferocious, but growing up in Plano, Texas, the creators of those novels might as well have lived on another planet. I’d arrived on campus hoping to get a job at the Centers for Disease Control. Instead, I caught the fiction bug and didn’t want a cure.

I modeled my early writing and my nascent sense of what a writer is on Jim. I started drinking vending machine cranberry juice. I already had the freckles. Jim was and is a character-driven writer, a character-driven teacher, for whom analysis of plot as an element of craft always seemed a bit low. The message was: if your characters are alive, they find the story for you. But my characters groped in the dark, and I left school four years later with a novel full of fascinating eccentrics who never did a thing.

I brought my manuscript with me when I moved to New York after college. Now that I knew a little about how to write, I figured I should learn how Writing becomes Books. I got an entry-level job at a publishing house, where I worked on other people’s novels. During my free time, I started submitting my own. Five years later, I’d amassed 76 rejections and had just been accepted to a fiction writing grad program in California, when a fellow assistant waved me over to her cubical.

She knew someone who knew someone who was looking to fill a pseudonymous writing gig: A male writer had begun a mass-market young adult series, and he was too busy to finish it. They wanted someone to use his pseudonym, adopt his characters and his voice. I’d been speaking in male writers’ voices for as long as I’d been writing—in fact, I hadn’t learned how to stop speaking in male writers’ voices. Let’s face it: I was speaking in Jim’s voice.

My favorite thing about my job at the publishing house was drafting the flap copy for the inside cover of a book, which requires assuming the style and cadence of a story in order to sell it. I suspected this pseudonymous side-hustle would engage the same skill set but in a longer format. Plus, I was about to be living on a grad student’s stipend. I was in no position to pass up seven grand.

But I still didn’t know how to write a book where anything happened. And the series I would be writing had to be heavy on plot. So a few weeks before I left New York, I recruited a screenwriter friend. We spread out a blanket in Central Park, popped some cheap Prosecco, and as the sun dipped over the Hudson, she schooled me on story beats—the three-act structure, the B-story, the excruciating Dark Night of the Soul.

I wondered: What about character? Wouldn’t taking on an already existing protagonist feel like sleeping with a stranger before you’ve had the chance to flirt? With my new knowledge of plot, I figured I could get my character to the party for the climax scene… but how would I know how she felt about being there? Doesn’t that make all the difference?

What I learned was it makes more sense to treat characters as if they’re already fully formed. Even now, when I draft a new novel, I don’t set out to construct someone from scratch. I encounter my characters in media res, getting to know souls already alive in a world. I don’t always like them, but I’ve learned it’s not up to me to change them. That’s the story’s job.

Meanwhile, I entered grad school, where I heard further evidence that plot is for hacks. In my free time, I hacked away at my plot-heavy pseudonymous series. I studied the previous male writer’s style and looked for places where I could change it—first a little, then a little more, then a lot. I instilled the secondary characters with new vigor, giving them opportunities to alter the destiny of the series.

The deadlines were so insane—two weeks per 70,000 words—that I had no time to ponder theories of identity and authorship. I typed fast and loose anywhere I could: at the bowling alley where my grad student friends hung out, by the pool at my rented farmhouse in northern California, in the backseat of my boyfriend’s Chrysler en route to his winery job. I fell in love with story structure, with the mechanisms of plot. I found that my plots generated character, instead of the other way around.

By the time I taught my first undergraduate Creative Writing seminar, I had my own novel to hold up to my students—even if its cover bore someone else’s name. It wasn’t going to win any awards, but I was proud of what writing that book taught me. I told my fresh-faced students I was losing my faith in character. If character was anything, it was an alchemical function of plot. I told them how beautiful, how illuminating plot can be. Plot separates fiction from life. Plot is numinous and keen.

And somewhere during my crash-course in commercial novel-writing—one year and four pseudonymous books later—I got an idea for a story of my own. It didn’t start with characters, but I knew they were out there, eager to flirt.

My new novel is about a male novelist writing bestselling romance books under a female pseudonym. It’s about the women he writes and the women he writes for. It’s about the female editor whose dreams get rearranged when she learns her author’s true identity. It’s about finding your voice with fiction, always my favorite lie.

_____________________________

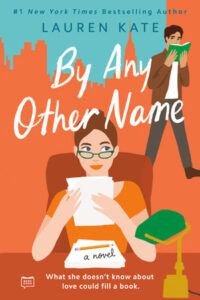

Lauren Kate’s By Any Other Name is available everywhere that sells books.