My Heroes: On Travel Memoirs by Black Women Writers

Nneka Okona on Books that Brought Her Comfort and Courage

Earlier this year, as I celebrated my 30th birthday at home with only a roasted chicken, garlic mashed potatoes, and sautéed green beans as company, I thought about how much travel meant in me, not only as a woman—but as a black woman. I joke a lot with my father about how travel is in my blood. I’m the daughter of an immigrant. My father came to this country some 40 or so odd years ago from Lagos, Nigeria, making me a first generation Nigerian American. It wasn’t until nine years ago when I completed the paperwork to get my passport and left the country on my first international trip to Kingston, Jamaica, that a part of me was reignited. It felt like I was reawakening to a dormant aspect of my psyche and spirit.

And I ran with it.

Three years later, I traveled to Madrid and became profoundly aware of my Blackness, more than I ever had in my hometown of Stone Mountain, Georgia, where I was never different and was always surrounded by people who both looked and sounded like me, with familiar Southern accents and lingering drawls. When I think about the nine months I spent in Madrid, all the traveling I did while living there and all the travel I have done since then, my memories are framed by a sense of others cowering at my difference. Of feeling lonely and misunderstood and hungering for connection and less isolation. I wanted to stop experiencing daily microaggressions, and I wanted to be done with the exhaustion of dealing with them.

But I also wanted for my lived experience to matter as is, to not need to be justified with a laundry list of examples and verifiable examples. I wanted my anguish to stand strong and true on its own and for other expats to stop telling me I was being too sensitive, reading too much into things and holding too much of a chip on my shoulder. I wanted to stop being told my blackness came with a responsibility I must uphold and that it was my role to explain who I was, how I was, and to be a graceful teacher whether I wanted to or not. I wanted for ignorance to not be bliss and for what I was experiencing to not be treated with willful obliviousness.

I turned to books. The words of other black women, the traveling, wanderlusting ones who had gone before me, experienced the same things I had or other things I hadn’t, were ministry to my soul. Before travel memoirs became a phenomenon, before the Elizabeth Gilberts and Cheryl Strayeds of bestselling contemporary travel writing, there were Black women writers trailblazing in this ever-shifting genre.

Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica, is Zora Neale Hurston’s firsthand account of her travels to Haiti and Jamaica in the 1930s to both experience and understand voodoo and its surrounding cultural context. It’s less a journey of personal growth, as most travel memoirs tend to be, and is instead a living and breathing historical account of an oft misunderstood and demonized cultural and spiritual practice.

Fifty or so years later, Maya Angelou’s All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes was published. In this work, Maya writes about her experience living among a group of black American expats in West Africa—Ghana to be exact—and the inner revelations surrounding home, belonging and racial and ethnic identity. The essence of this work is brought home in this quote, a personal favorite of mine:

Perhaps travel cannot prevent bigotry, but by demonstrating that all peoples cry, laugh, eat, worry, and die, it can introduce the idea that if we try and understand each other, we may even become friends.

* * * *

In Madrid, a friend recommended Lori Tharps’ Kinky Gazpacho: Life, Love and Spain because the experiences I chronicled for her reminded her of Tharps’ writing. Tharps tells her story of Black identity through the personal renaissance she experiences while coming to understand Spanish culture, weaving in childhood memories, as she finds herself not only as a woman, but a Black woman.

From there I wandered to Faith Adiele’s Meeting Faith, a poignant travelogue of one woman’s journey to becoming Thailand’s very first Black Buddhist nun. Adiele juxtaposes so many seemingly opposing forces through the pages of her memoir—eastern and western religious philosophy, connectedness and the isolation of the path to ordination, redefining her life and what was important her in real time. Reading this book felt as if I was joining her as a companion on a journey.

Emily Raboteau’s Searching for Zion was the memoir that most piqued my intellectual curiosity. Raboteau has a gift for telling a vivid story, and it makes you want to research and learn more about untraveled corners of the world and the stories waiting to be told there. Her memoir is as much a tale of self-discovery, of finding an inner sense of belonging as a biracial woman, as it is a chronology of her travels from Israel to Jamaica to Ethiopia, where she traces the roots of Black Jews, Rastafarians, and the historical ties that connect them all.

Amanda Epe’s Fly Girl was my next read. Epe’s account of jaunting across the world as a flight attendant for British Airways is more lighthearted, but it nonetheless touches on things that resonate with me deeply. She documents the cultural clashes she experiences with each new country and city—as a woman, as a woman of color, as a black woman—and even talks openly about discrimination in the airline industry. As a black woman with darker skin, she describers what it felt like through the flight attendant application process, being rejected time and time again, being “the only one” when she first started out, and how she bore witness to gradual change.

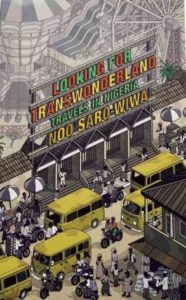

Perhaps the most soul-stirring read of all was Noo Sara-Wiwa’s Looking for Transwonderland, which took me through the heart of Lagos, where I have my own roots as well. To this day I’ve never visited Lagos; there are family members who still live there I’ve yet to meet. Reading Sara-Wiwa’s captivating account of her travels in Nigeria put chills down my spine.

All these books were as consolatory to me as they were informative and inspiring. And these five travel memoirs written by black women allowed me, in a small way, to feel vindicated—to feel that women like me are worthy of publishing travel stories and being seen and heard for penning them, just like those of other white women who had written their stories too.

* * * *

Some months ago, I was talking with another black woman about how with each trip I take, travel means so much more to me—especially knowing the history of travel as a Black person in America. I told her many of my relatives and friends had no interest in traveling and that this frustrated me. She cautioned me, gently, in not being haughty and judgmental and suggested I read The Green Book.

I was confused. I wanted to be right. I mean, why wouldn’t people want to see more of this big, vast world if given the chance? But after reading The Green Book—otherwise known as The Negro Motorist Green Book written by Victor Hugo Green—I had so much more perspective.

The Green Book was first published in 1936 and was followed up with many subsequent, updated editions through the years until its final publication in 1966. The idea behind The Green Book was simple: to provide an all-encompassing resource for black Americans who wanted to road trip through the country. In the Jim Crow era, traveling while Black could come with many roadblocks—being refused a stay at a hotel, not being able to refuel your car during your journey, arriving too late in sundown towns and fearing for your safety. With The Green Book, you had a quick guide at your fingertips to navigate all these different scenarios. Eventually, Green expanded his guide to include international locales and even founded a travel agency.

Travel remains a privilege even today, and its important to remember the fraught history of black Americans who feared exploring their own country because of the color of their skin. And so I celebrate the names and written voices of these black women travel writers—Zora Neale Hurston, Maya Angelou, Lori L. Tharps, Faith Adiele, Emily Raboteau, Amanda Epe, and Noo Sara-Wiwa—as heroes because they were brave and because they believed enough in what they had to say to share it with the world. I uphold them high and mighty for the other Black women who will now come after them—traveling, seeing the world, transforming, growing, shifting, tenaciously writing about it, inspiring others, continuing this ripple effect—following the path they so graciously trailblazed.

Nneka Okona

Nneka M. Okona is a writer based in Atlanta that pens pieces on food, travel, drinks, wellness and the occasional bookish feature. She's currently working on her first book, a memoir that will chronicle her coming-of-age experience living in Madrid, Spain.