My Friend, the Legendary Porn Queen

Catherine Gigante-Brown on Jane Kamensky’s Biography of Candida Royalle

Reading a friend’s biography is a strange phenomenon. In her in-depth biography of feminist adult filmmaker (and former erotic performer) Candida Royalle, Jane Kamensky splays Royalle open wider than any hardcore endeavor ever did—including 1979’s Hot and Saucy Pizza Girls (with its tagline “We deliver!!!”), Royalle’s favorite of her 40 plus X-rated pics, which she loved for its sheer zaniness. She even kept the costume—micro shorts and a skimpy, white tie-off top—which were found among her personal effects when she died after an extended bout with ovarian cancer.

I knew her as Candice. Candice Vadala. In private, porn people call each other by their real names. I’m a former smut scribe myself, having written scores of scripts, essays and video reviews under the names “Ariel Hart,” “Pearl Chavez,” et al.

In fact, I’m a footnote in Kamensky’s book, where she cites my 1991 Playgirl article “Surviving the Sex-Vid Explosion.” But I like to think that I was a bit more than a footnote in Royalle’s life; I was her friend.

We met in the early 1990s. Candice was gracious enough to grant me interviews when I was working on a piece. When I split with my first husband, a rage-filled, failed drummer, like a protective big sister, Candice confided in me, “I’m glad it’s over. We all felt so sorry for you.” She knew too well the volatile musician’s temperament. “My dad was a drummer,” she told me wistfully.

Professionally, Candice was deeply committed to making lovingly-crafted adult films and videos. This is why she co-created Femme Productions in 1984. Candice pretty much invented couples erotica.

“Candida Royalle’s” half-page New York Times September 10, 2015 obituary caught the eye of the newly-appointed director of Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Jane Kamensky, who described the obit as:

lauding the movies she “infused with plots, passion, seduction and even romance,” as well as her work as a founder of Feminists for Free Expression, “a so-called sex-positive organization” that had challenged efforts to censor pornography from the left and right alike…

The esteemed library has the papers of radical feminist Andrea Dworkin as well as those of Women Against Pornography plus other archives which focus on sexual violence and women’s liberation. Candice’s archives seemed a perfect fit to Kamensky, a respected historian who also taught American History. Candice was feminist American history.

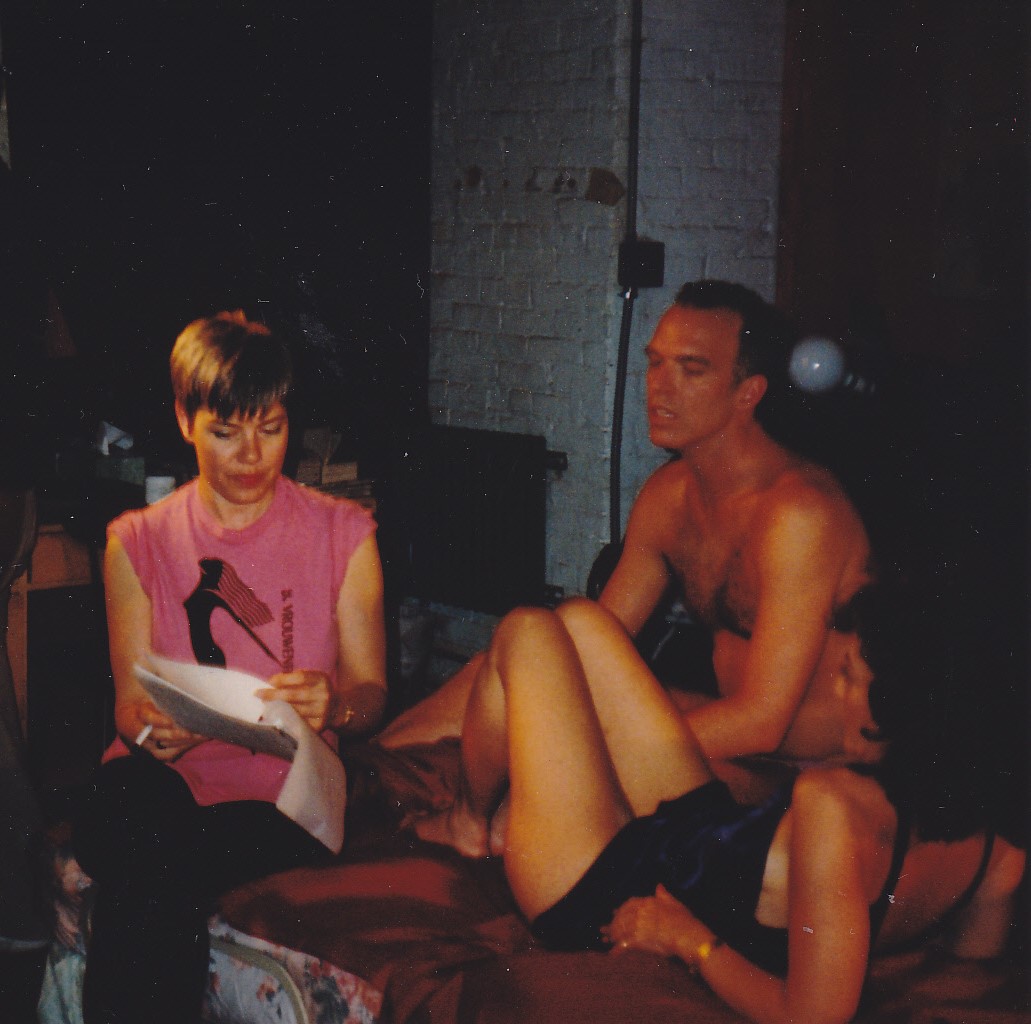

Candice blocks out a scene with two actors on the set of Revelations (1993), care of the author.

Candice blocks out a scene with two actors on the set of Revelations (1993), care of the author.

All told, the Royalle Papers at the Schlesinger would encompass 106 file boxes, 109 folders of photos, 209 videotapes, three archived websites, tens of thousands of posters, costumes and emails. I couldn’t help but wonder if Candice and my personal “cancer correspondence” was among them.

When I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2013, Candice was all too familiar with the chemo dance, having battled ovarian cancer since 2009. She was a source of invaluable advice like, “No matter how awful you feel, force yourself to get out of bed every day, take a shower and get dressed. I guarantee you’ll feel better.” It was true.

Candice also recommended I get a copy of Greg Anderson’s Cancer: 50 Essential Things to Do, a sound rec from one Chemo Girl to another. I did; it helped. When Candice suggested you do something, you did it.

While Candice was helping me deal with my mortality, she was grappling with her own. A recurrence of ovarian cancer had her starting a third cycle of chemotherapy in conjunction with my first. A couple of years later, Candice approached me at CineKink event, she leaned in close and whispered, “It’s baaack!” then walked away. I was shattered. I was in remission; she was metastatic. I think this was the last time I ever saw her.

Candice was feminist American history.

In September 2015. Kamensky was newly at the helm of the Schlesinger and reached out to the executrix of Candice’s estate, her friend (and mine), human sexuality writer and actress Veronica Vera, just weeks after Candice’s passing. Vera arranged to have Candice’s archives sent to the Schlesinger—and invited Kamensky to Candice’s New York City memorial in November.

Attendees were asked to wear red, Candice’s favorite color. I was among those invited to speak at the celebration of her life. There was a buffet afterwards and I volunteered to make red roasted peppers, a dish I think Candice, an Italian-American kid born in Long Island, would have enjoyed. It brought me to tears looking out at the sea of crimson taking in the hundreds who knew and loved Candice.

Memorial guests were given the opportunity to take a tiny glass vial of Candice’s ashes. We were told to scatter them someplace beautiful, someplace Candice would have liked. At my upstate New York cabin, I dusted some of at the base of a Japanese maple. It is now known as “Candice’s Tree.” The leaves blaze bright red in the autumn.

Kamensky took Candice’s ashes too. She offered them to the Schlesinger Library as part of Candice’s personal effects; they refused. I guess the detritus of human remains, unlike porn panties, are taboo.

On March 12, 2024, Jane Kamensky’s exhaustive biography of Candida Royalle was released. In addition to using the Royalle Papers, which included the diaries Candice kept for 50 plus years, Kamensky interviewed more than 20 people from Candice’s life—like her ex-husband Per Sjöstedt and her sister Cinthea. Kamensky pored over a lifetime of memorabilia.

The book is a whopping 544 pages with 70 odd pages of footnotes and addendum, and more than 50 photographs and illustrations, many created by High School of Art and Design graduate Candice’s own hand.

When I saw the photo of Candice on page 32 as a scrawny four-year-old in a Peter Pan hat, so vulnerable with her crooked bangs and cuffed anklets, I welled up. I wanted to hug her. I wanted to ask her questions. I wanted to look into her lovely eyes that always sparkled with intelligence—and naughtiness. I wanted to hear her laugh again. But I couldn’t. Candice was almost nine years gone.

Some nights after reading Candice’s story, I couldn’t sleep. My heart ached for the little girl whose mother left without a word, without a trace, when she was just 18 months old. For the tween whose father pleasured himself while he watched Cinthea sleep in the bedroom she shared with Candice. (“I have a sick father,” she scribbled in her diary, “He’s very, very mixed up! And no one can help him.”) I tossed and turned, thinking of how Candice was blamed for a near rape at 13, and was haunted by her drug use as a twenty-something to dull her emotional pain.

I think Kamensky got it right. She skillfully juxtaposed Candice’s story against developments in the women’s movement at the time, deftly dancing between the two, sprinkling in footnoted diary quotes and reflections from key players in Candice’s life. The book captures Candice’s humanity but not her wicked wit. Or her vibrance. Or her generous spirit. Or the grace with which Candice moved through the world. How could it?

Kamensky never had the chance to hear Candice sing “The Little Tomato” (in a skintight red PVC minidress, no less!), a song she wrote as part of White Trash Boom Boom, an avantgarde theater troupe in 1970s San Francisco. She never got to trade Facebook barbs about who looks nerdier in a group pic, bundled up in against snowstorm. Or get showered with emails of hope when faced with cancer: “Keep staying strong and positive, Cathy. It’s not everything but I think it definitely helps.”

Biography is, by definition, an invasive genre. If Candice were alive and in control, I wonder if she would have been so forthcoming about her father’s unhealthy sexual interest in his daughters, included her 1978 composition called “Suicide Note” or had been so painstakingly detailed about her heroin use, multiple abortions or hepatitis C diagnosis.

However, having known Candice, I think she would approve of the tits-to-the wall, bare-all biography. If it helped someone not feel “less than,” if it spared just one woman sexual shame, then to Candice, it would be worth it.

Toward the end of Kamensky’s book, she writes of Candice’s worrying:

“What will become of it?” she asked in her journal. Would her diaries and photos “end up in junk stores & flea markets”? She had longed to speak her piece, her way, “rather than wait for strangers to paw at my memories without even knowing my name.”

And thanks to Kamensky, the names Candida Royalle and Candice Vadala are immortal.

So, yes, I think Candice would be proud of the book. I only wish she were here to see it.

*

Catherine Gigante-Brown is a writer of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, plays and screenplays whose works have appeared in publications as diverse as the New York Times, Seventeen and Screw Magazine. She is also the author of seven novels, all published by Volossal, including her latest, Cry of Silence, which gives a nod to Royalle and 40 plus porn people.

Catherine Gigante-Brown

Catherine Gigante-Brown is a writer of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, plays and screenplays whose works have appeared in publications as diverse as the New York Times, Seventeen, and Screw Magazine. She is also the author of seven novels, all published by Volossal, including her latest, Cry of Silence, which gives a nod to Royalle and 40 plus porn people.