“My First Porno, My First Dildo, My First Love.” On José Donoso’s The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria

Gabriela Wiener Considers a Beloved, Life-Changing Book

I want to be a Donoso girl

Sometimes I have the unsettling feeling that my life, and as such my writing, are the product of a queer Chilean man’s fevered imagination. And that I have followed the script to a tee and pushed to the limit other people’s fantasies, which I believed — and ultimately made — absolutely my own. I’m even more certain that I would have hated having owed a single one of my paraphilias or literary and sexual habits to some regular Chilean man. Luckily, that’s not the case. The narratives of José Donoso, and later Pedro Lemebel, were my foundational dissident readings — first in the closet, then as part of the queer marica carnival — and all those stories burned inside me until they compelled me to come out with my own.

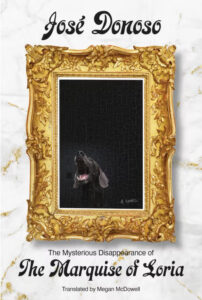

I don’t know where I got my copy of The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria. I only know that the books with black covers published by Seix Barral’s Bilblioteca Breve series always seemed suspicious and thus magnetic to me, even when they lived up to the series title and were as brief as this one. What was suspicious about this particular book? Its long title, perhaps, and the back-cover description announcing the novel as a more or less minor work of the erotic picaresque genre, masterfully written by one of those most suspect of men: a writer of the Latin American Boom. Everyone knows that 100 percent erotic literature — that is, literature written to excite — can only be written from inside the dark workshops of our closets. That’s why Lemebel, who wrote from the street, did not write erotic literature but something quite different. Donoso, however, did.

The little marquise will reveal a search not for what but for whom, and not only for others, but also for the self; not only for the body but for the being.

I must have been fourteen or fifteen years old when I first read The Marquise of Loria. I would read it many more times, countless when it came to my favorite parts — for example, the scene when Mamerto Sosa, the marquise’s hired notary, with his “mothball smell” and his “small but indomitable horn,” suddenly falls quiet, “as if…” That is, he dies during copulation, after feeling the marquise “squeezing him with a short and violent orgasm.” Oh, the moment when Mamerto slowly falls, “as empty and shapeless as a lightweight nightshirt.” I know that all of the sex scenes I’ve written in my life originated here.

Today, as I write this, I’m still holding the same volume from my teenage years, well worn from use, its black skin cracked by damp, the pages dyed sepia from dust and neglect. A life story only has room for a few books with which one truly cohabitates, as with a husband or a lover (or two, or three, or four). That’s what the Marquesita is on my bookshelf. I’d even say it smells like me. It was my forbidden book, my secret read. I turned to it when I was alone; it came immediately to mind when I heard the rest of my family go out the front door, and if they didn’t go out I’d find a way to lock myself in the bathroom with Donoso. Do I belong to the last generation to have masturbated to books? Maybe, but I’m not nostalgic; I have no doubt that these days some people masturbate to social media posts. Reading can still be eroticized.

Rereading today, I can recognize the parts that made me quiver, the passages where I paused to compulsively go over the same lines again and again. Ever faster, ever more urgently, a tightrope walk between culture and pleasure, one hand inside myself and the other in the book, until I came to an end. But the book was endless. I had to wipe it with toilet paper after reading it, and it wasn’t exactly tears I was cleaning off. The cover wasn’t pink and the prose wasn’t purple, and it didn’t have a tattletale image on the cover like the books published by La Sonrisa Vertical (The Vertical Smile, an imprint of Tusquets Editores). It wasn’t arrogant or blatant. It wasn’t performative or pompous. It was a book with a discrete cover, perfect for teenage girls who still lived in all the closets, both figuratively and literally, and were happy there, only there. It could have been mistaken for a YA novel. I liked to think that no one knew my secret, that while my mother was reading feminism for the first time and my father was reading Marx for the umpteenth time, I was cultivating a new genre that augured my future not so much in autofiction as in autoeroticism.

A few years ago I was one of a group of writers asked to choose five objects to form a sort of personal museum inside a suitcase, part of a larger exhibit that would be shown at book fairs. Along with other well-loved objects, including my dead father’s broken eyeglasses and a photo of my mother as a child with a shotgun, I chose my copy of the Marquesita.

Donoso’s “little book” (people always refer to it in the diminutive —oh, how little they know), has more than enough merit to figure in my top five of all time. Because while the patriarchy was keeping me away from Anaïs Nin and Marguerite Duras, before I discovered porn and postporn, before Paul B. Preciado, long before I cut my teeth writing the sexual horoscope for a Spanish magazine marketed to dirty-minded men, before the columns, articles, and books about the body and desire that put food on my table, I embarked upon sex with myself — put this way, I feel my words impregnated with a Donosian erotic flow — in the most cultured way possible: touching myself as I read about this insatiable character’s adventures. For me, the Little Marquise was my first porno, my first dildo, and my first love.

José Donoso published the book in 1980, in one of his many times of exile between periods spent in Chile. He had already depicted his own social class in Coronation, and had shown to the world, maybe not who he was, but at least what he was capable of, in Hell Has No Limits, which Arturo Ripstein made into a movie. It had been a decade since The Obscene Bird of Night had made him into the best writer in Chile, and one of the best in the Western canon. By then he was married, had adopted a Spanish daughter, and regularly attended dinner parties in Barcelona with the other Boom writers, whose wives had to endure their hours of conversation while laughing at all their jokes.

They all felt omnipotent and immortal then, capable of making equally deft incursions into the total novel and the short story, in Santiago, Lima, or Paris, into the Nobel Prize and clochardismo, into dramaturgy and politics, into public office and erotic little novels. Universal masters, they set out to include eroticism in great literature, but not to write great erotic literature, which Vargas Llosa once declared nonexistent. But of course it does exist, though not everyone gets it right. I’m not here to establish hierarchies — that compulsion is so twentieth century — but I will go to the mat for the potential greatness of genre literature: for me, while neither Memories of My Melancholy Whores (Márquez) or The Bad Girl (Vargas Llosa) can today be considered great erotic literature, the transgressive and far less well-known antics of the Marquise of Loria can.

As always, the betrayal starts with a deviation from tradition. Starting from the book’s title, we are prepared to be titillated and to jealously guard our secret pleasure, as with any story that’s billed as licentious, with all of that genre’s most endearing cliches and predictable ingredients, including mystery, death, and games of seduction. But it’s all leading us toward an entanglement on another plane of reality that is much more Donosian than excitatory —a phantasmagoric and audacious plane that is very far removed from any pink-covered bodice ripper.

On her way to becoming a full-fledged European, Blanca, a young Nicaraguan woman and the daughter of Latin American diplomats stationed in Madrid, marries Paquito, the young marquess of Loria, but his sudden death from pneumonia makes her into an almost instantaneous and providential widow. As in other works of the genre, we have the premise of a young and attractive woman who, at her husband’s death, is consumed by her unusual appetites and iconoclastic spirit, seemingly in permanent revolution.

Donoso also presents Blanca as a woman with white skin, because canonical desire has always been white, and white the normative body. Still, there are constant allusions to Blanca’s condition as an immigrant and to her cultural difference, her concern with wealth in the face of European squandering and wastefulness. The marquise’s gaze looks from the South to the North, with all the mischievousness and tender mockery of those who, from below, look upon those above.

Though the novel’s structure could be called classic, Blanca’s tour de force is much more complex than any story in the Decameron, and Donoso’s imagery is closer to the Marquis de Sade’s. To start with, everything we learn about the marquise passes through a filter of humor, satire, and even ridicule. That, too, is a feature of canonical erotic literature as well as the literature of the closet: saying things as if you didn’t mean them, hiding behind the curtains of irony and mannered language.

But Donoso manages to ironize the very rhetoric of the excitatory text. Not for a second does he neglect his corrosive critique of elites, and it only makes the joke more enduring. I know I’m still laughing. I’ve been laughing for thirty years. And the irony can turn bitter and thoughtful at times, as it does in Donoso’s Sacred Families: Three Novellas or in The Obscene Bird itself. This Chilean author will take his little marquise through an endless festival of desire and experimentation, and in this erotic-thanatological tour, his character will raze bodies, inhibitions, norms, genders, binaries, and speciesisms.

From her early obsession with her callow husband’s prominent but not so lively member, through a variety of solitary mystical raptures and successive, perverse rituals where bodies are consumed — from the most honorable to the most libertine, from the tenderest to the most decrepit — all the way to her transpersonal encounter with a ravaging dog “who seemed to offer something more,” the little marquise will reveal a search not for what but for whom, and not only for others, but also for the self; not only for the body but for the being. Until the memorable and disorienting final twist that ungenres the novel and definitively hurls the book from the pigeonhole of the great, magnificent little genre novel into a territory that is much less defined, but transcendent.

Just who is our dear little marquise looking for along the tricky pathways of desire? Herself, as the saying goes? But is that self the one that others see, or the elusive one reflected in the mirror, the one who chops off her hair to finally become herself ? Is she really a woman? Is she a body, or all bodies? Is she flesh and blood, or is she, not at the end but from the very beginning, a ghost who crosses some ineffable threshold of our desire only to dissolve back into the mist from which there is no return? Is she the delicious fictional object of lust and the vessel for all of one man’s fantasies — or all of humanity’s? Or even of all the living beings on earth?

I imagine José Donoso creating the little marquise the way the Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar created his dozens of feminine characters, his “Almodóvar girls”: exaggerating them, pushing them to the edge, turning them into trans women, into transmutations of their own still lives. Making them into the women he could only dream of being, but whom he loved because they taught him to dream: mothers, daughters, lovers, friends, transvestites smeared with eyeliner, shitty sex, and impossible love.

The little marquise of Loria is a Donoso girl. The girl that Donoso never was and always wanted to be, and, just maybe, actually was and always will be.

Some years ago, when Pedro Lemebel was still alive, I interviewed him after he won the José Donoso Prize. I asked if something had to have changed for him, an extravagant queen, to win a prize named after a man who had lived his homosexuality in painful silence. “I don’t know that Donoso really did live his homosexuality in painful silence, as you put it,” Lemebel replied, “or just in a comfortable closet.” I think we can allow ourselves this uncertainty.

Pedro was right when he said that Donoso was “a fossil of the bourgeoisie” who didn’t have much in common with his own “queer and carnivalesque martyrdom,” but precisely because of the contrast, their writings and lives speak to us of the tensions between high and low, between inside and out, between silence and outcry in the writing of diversity and dissidence in Latin America — which always involves pain and blood.

The little marquise of Loria is a Donoso girl. The girl that Donoso never was and always wanted to be, and, just maybe, actually was and always will be. I also wanted to be a Donoso girl, a little clever, just a little silly, a little saintly, a little slutty. At some point I figured out how to create my own character and put it out into the world, but only because others like Donoso and Lemebel taught me to do it, whether behind closed doors or out on the church’s front steps. Another instance of literary art’s applied beauty: it teaches us to be someone else, and to feel that we are always this person, and others, and others still. I love the marquise because I can be her the way I can both be and not be Madame Bovary or Anaïs Nin, I can be the person I was and that other who desires yet another.

And here we come to the twist of the falsely masturbatory little novel: the mysterious occurrence of getting off to good literature, fantastic or existential. Or its flirtation with death, with Bataille or Foucault. And how all this is taking place in Donoso’s imagination, opening his closets full of colorful disguises for us, but also contradictions he suffered, unresolved conflicts, and fears and anxieties worn on his sleeve. Forget that he once wrote a letter to his bride telling her how he “was moved to his marrow” when he saw two men showing their love, and felt “envy, desperation,” “a desire to have exactly” what those two had, and at the same time “a vehement wish not to be like them,” a “terrible temptation” that he admitted hurt just as much or more to realize as to not.

Forget that he referred to this as his “primary problem.” Forget that he admitted he didn’t know where it came from, why it existed, what it meant. Forget that he referred to the desire and love for others like himself as “homosexual envy.” Like the lemon-eyed dog devouring him, Donoso seemed to see his own “alabaster body stained with bruises and welts, striped with scratches, clearly marked by the beast’s fangs, making [him] into a sort of tenebristic, tremendista, and tragic saint, a horrific and bloody martyr.” Like the queer Lemebelian martyr.

And that’s why it’s a pleasure to see him like this, dressed as the little marquise, being the marquise of Donoso, trying out everything: homosexuality, threesomes, polyamory, scatology, interspecies love. And how can these images not remind us of his daughter Pilar, writing, publishing to acclaim, freeing herself from the paternal yoke and, simultaneously, dying. And freeing him as well.

Sometimes I have the unsettling feeling that my life, and as such my writing, are the product of a queer Chilean man’s fevered imagination. I even live in Madrid. I had forgotten that the novel is set in the city that has sheltered me for over a decade now. I just remembered it now, in these recent days of nostalgic rereading, as I’ve gotten turned on again and walked down the same streets the marquise walks, the areas around Casa de Campo and Puerta de Hierro. And I’ve gone to Retiro Park and thought I saw the little marquise beside her dark, wild, pale-eyed dog, like a mutant, solitary, savage creature, showing me the way out of this gray labyrinth.

__________________________________

From The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria by José Donoso, translated by Megan McDowell. Copyright © 2025. Available from New Directions Publishing.

Gabriela Wiener

Gabriela Wiener is the author of Sexographies (2018), translated by Lucy Greaves and Jennifer Adcock; Nine Moons (May, 2020), translated by Jessica Powell; and six other books of crónicas and poems published in Spanish. She writes regularly for the newspapers El País (Spain), La República (Peru), and others in the US and Europe. She lives in Madrid.