As I travelled, I watched the landscape—lochs and hillsides, the trees still winter-bare, etched against a soft, grey sky—and all the time my empty hand moved on my lap, tracing the pattern the branches made, smoothing the lines of the hills.

That drawing could be a way of not thinking and a barrier against feeling I didn’t need a psychotherapist to tell me. Once upon a time I would have whiled away the journey by making up stories, but since Allan’s death, this escape had failed me.

I had been a writer all my life—professionally, thirty years—but the urge to make up stories went back even further. Whether they were for my own private entertainment or printed out and hand-bound as presents for family, whether they appeared in fanzines or between hardcovers, one thousand words long or one hundred thousand, sold barely two hundred copies or hovered at the bottom of (one) best-seller list, whether they won glowing reviews or were uniformly ignored, my stories were me, they were what I did. Publishers might fail me, readers lose interest, but that story itself let me down was something that had never occurred before.

Strange that I could still take pleasure in sketching, because that was so completely associated with my life with Allan that the reminder ought to have been too painful. He had been a keen amateur artist, a weekend watercolorist, and, following his relaxed example, I’d tried my hand on our first holiday together and liked the results. It became something we could do together, another shared interest. I had not painted or sketched since childhood, having decided very early in life that I must devote myself to the one thing I was good at in order to succeed. Anything else seemed like a waste of time.

Allan had never seen life in those terms; he came from a different world. He was English, middle-class, ten years older than me. My parents were self-made, first-generation Americans who knew and thought little about what their parents had left behind, whereas his could trace their ancestry back to the Middle Ages, and while they were nothing so vulgar as rich, they had never had to worry about money. Allan had gone to a “progressive” school where the importance of being well-rounded was emphasized and little attention given to the practicalities of earning a living. And so he was athletic—he could play cricket and football, swim, shoot, and sail—and musical, and artistic, and handy—a good plain cook, he could put up a garden shed or any large item of flat-packed furniture by himself—and prodigiously well-read. But, as he sometimes said with a sigh, his skills were many, useful, and entertaining, but not the sort to attract financial reward.

We’d been living modestly but comfortably mainly on his investments, augmented by my erratic writing income, until the collapse of the stock-market. Before we’d done more than consider ways we might live even more modestly, Allan had died from a massive heart attack.

I had no debts—even the mortgage was paid off—but my writing income had dried to the merest trickle, and the past year and a half had eaten away at my savings. Something had to change—which was why I was on my way to Edinburgh to meet my agent.

I hadn’t seen Selwyn in several years. At least, not on business—he had come up to Scotland for Allan’s funeral. When he’d sent me an email to say he would be in Edinburgh on business, and was it possible I’d be free for lunch, I’d known it was an opportunity I had to take. I’d written nothing to speak of since Allan’s death, one year and five months ago. I still didn’t know if I would ever want to write again, but I had to make some money, and I wasn’t trained or qualified to do anything else. The prospect of embarking, in my fifties, on a new, low-paid career as a cleaner or carer was too grim to contemplate.

I’d hoped having a deadline would focus my mind, but by the time I arrived at Waverley Station the only thing I felt sure of was that, as stories had failed me, my next book would have to be nonfiction.

I arrived with time to spare and, as it wasn’t raining and was, for February, remarkably mild, I took a stroll up to the National Gallery. Access to art was one thing I really missed in my remote country home. I had lots of books, but reproductions just weren’t the same as being able to wander around a spacious gallery staring at the original paintings.

It was hard to relax and concentrate on the pictures that day; my mind was jittering around, desperate for an idea. And then all of a sudden, there she was.

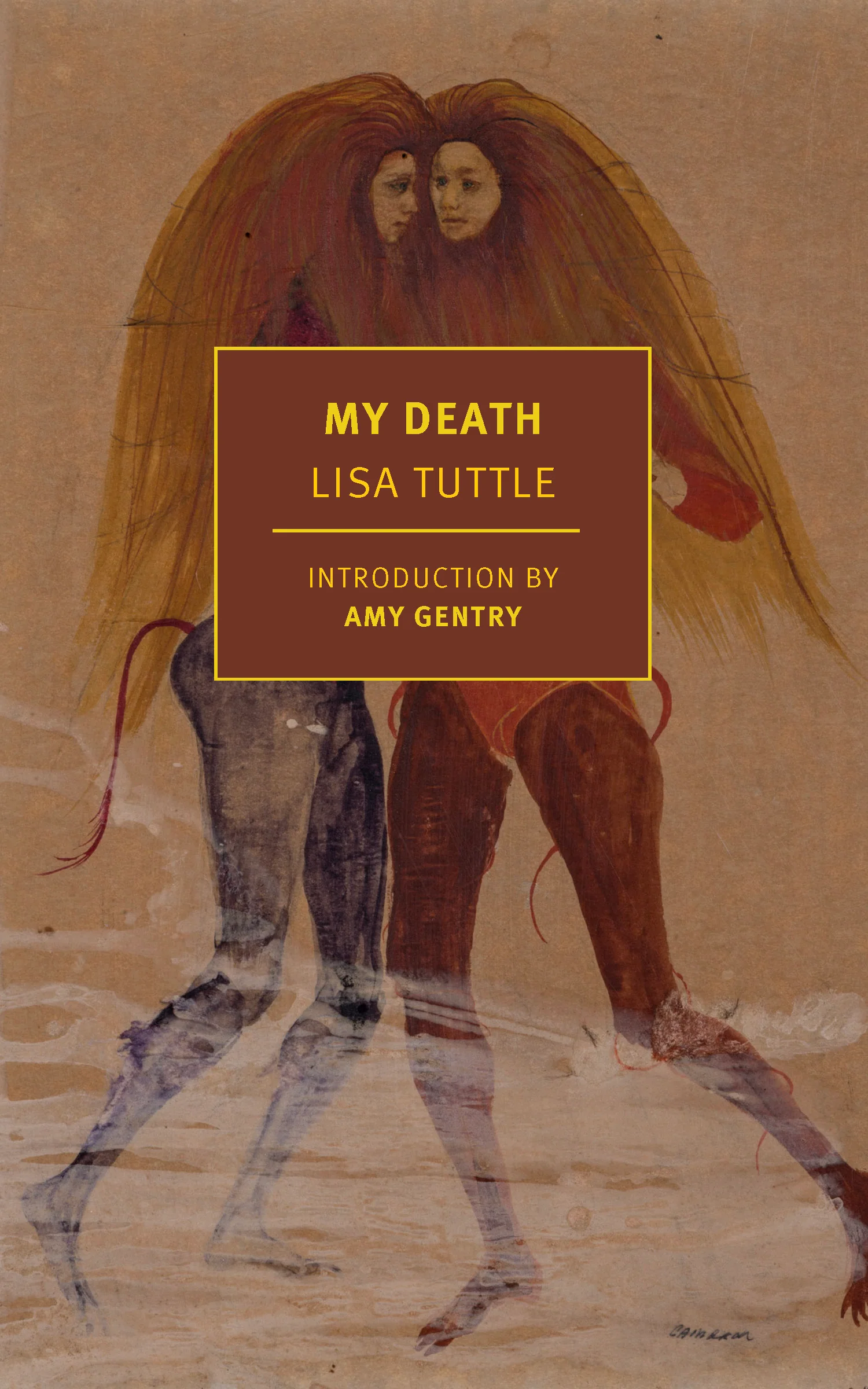

I knew her, standing there, an imposing female figure in a dark purple robe, crowned with a gold filigreed tiara in her reddish-gold hair, one slim white arm held up commandingly, her pale face stern and angular, not entirely beautiful, but unique, arresting, and as intimately familiar to me as were the fleshy, naked-looking pink and grey swine who scattered and bolted in terror before her. I also knew the pile of stones behind her, and the grove of trees, and, in the middle distance, the sly, crouching figure of her nemesis hiding behind a rock as he watched and waited.

Circe, 1928, by W. E. Logan.

It was like coming across an old friend in an unfamiliar place. As a college student, I’d had a poster-print of this same painting hanging on the wall of my dormitory room. Later, it had accompanied me to adorn various apartments in New York, Seattle, New Orleans, and Austin, but, despite my affection for it, I’d never bothered to have it framed, and by the time I left for London it was too frayed and torn and stained to move again.

For ten eventful, formative years this picture had been part of my life. I had gazed up at her, and Circe had looked down on me through times of heart-break and exultation, in boredom and in ecstasy. I much preferred the powerful enchantress who would turn men into pigs to the dreamier, more passive maidens beloved of my contemporaries. The walls of my friends’ rooms featured reproductions of Pre-Raphaelite beauties: poor, drowned Ophelia, Mariana waiting patiently at her window, Isabella moping over her pot of basil. I preferred Circe’s more angular and determined features, her lively, impatient stare: Cast out that swine! she advised. All men are pigs. You don’t need them. Live alone, like me, and make magic.

I gazed with wonder at the original painting. It was so much more vivid and alive than the rather dull tones of the reproduction. Although I’d visited the Scottish National Gallery many times, I could not remember having seen it here before. Now I noticed details in it that I didn’t recall from the reproduction: the distinct shape of oak-leaf, and a scattering of acorns on the ground; a line of alders in the distance—alders, the tree of resurrection and concealment—and above, in a patch of blue sky, hovered a tiny bird, Circe’s namesake, the female falcon.

My fascination with this painting when I was younger was mostly to do with the subject matter: I liked pictures that told a story, and the stories I liked best were from ancient mythology. I had been sadly disappointed by all the other paintings by W. E. Logan that I had managed to track down: they were either landscapes (mostly of the South of France) or dull portraits of middle-class Glaswegians. Circe, which marked a total departure in style and approach, had also been W. E. Logan’s last completed painting. His model was a young art student called Helen Elizabeth Ralston—an American who had gone to Glasgow to study art. Shortly after Logan completed his study of her as the enchantress, she had fallen—or leaped—from the high window of a flat in the west end of Glasgow. Although badly injured, she survived. Logan had left his wife and children to devote himself to Helen. He paid for her operations and the medical care she needed, and during the long hours he spent sitting at her bedside, he’d made up a story about a little girl who had walked out of a high window and discovered a world of adventure in the clouds high above the city. As he talked, he sketched, creating a sharp-nosed determined little girl menaced and befriended by weird, amorphous cloud-shapes, and then he put the pictures in order, and wrote up the text to create Hermine in Cloud-Land, his first book and a popular seller in Britain throughout the 1930s.

The real Helen Ralston was not only Logan’s muse and inspiration, but went on to become a successful writer herself. She’d written the cult classic In Troy, that amazing, poetic cry of a book, which throughout my twenties had been practically my Bible.

And yet I’d had no idea, when I’d huddled on my bed and lost myself in the mythic story and compelling, almost ritualistic phrases of In Troy, that its author was staring down at me from the wall. I’d only discovered that in the early 1980s, when I was living in London and In Troy was reprinted as one of those green-backed Virago Classics, with a detail from W. E. Logan’s Circe on the cover. Angela Carter had written the appreciative introduction to the reprint, and it was there that I had learned of Helen Elizabeth Ralston’s relationship with W. E. (Willy) Logan.

Feeling suddenly much livelier, I left the gallery and went down Princes Street to the big bookshop there. I couldn’t find In Troy or anything else by Helen Ralston in the fiction section. Browsing through the essays and criticism I eventually found a book called A Late Flowering by some American academic, which devoted a chapter to the books of Helen Ralston. Willy Logan was better represented. Under “L” in the fiction section was a whole row of his novels, the uniform edition from Canongate. The only book I’d read of his was one based on Celtic mythology, which had been published, with an amazing George Barr cover, in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy line around about 1968. I remembered nothing at all about it now, not even the title.

After a little hesitation I decided to try In Circe’s Snare for its suggestive title, and I also bought Second Chance at Life by Brian Ross, a big fat biography of Logan, recently published. And then I noticed the time and knew I had to run.

__________________________________

From the first chapter of My Death by Lisa Tuttle. Used with the permission of NYRB Classics. Copyright © 2004 by Lisa Tuttle.