My 12-Hour Lunch Date with Joni Mitchell

David Yaffe on Trying to Keep Up with an Icon

When I was 15, I had a high school girlfriend who was a couple of years older than me—dog years in those days. She had a piano and a stereo in her room, and very tolerant parents. We were both music students at an arts high school in Dallas; she sang, I played piano. We had a ritual of lying on her bed together in pitch-darkness, taking in what we were hearing with everything we had—the Velvet Underground, Miles Davis . . . One day, she played me Joni Mitchell’s Blue. Years later Joni would tell me that when she made that album she was totally without defenses, as vulnerable as “a cellophane wrapper on a packet of cigarettes,” as she once put it. When one is 15, everything is new and raw. I was falling in love with a girl and falling in love with this music. Neither came to you. You had to come to them. I held on tight in those tender, cellophane years.

In time, I would learn that while Joni was famous for being tender in public she also had to be tough in private. By the time Blue was released in 1971, she had survived polio and a bad first marriage, and recently fended off a marriage proposal from Graham Nash, whom she had loved. I didn’t know about these things yet. But my need to know about this woman I heard on the record eventually brought me closer and closer.

Over the years, I would turn to Joni’s music, sometimes when I needed to hear her tell me, as she does in “Trouble Child,” that I really am inconsolably on my own: “So what are you going to do about it / You can’t live life and you can’t leave it.” Ouch. And yet, in that voice, in those chords, there was nevertheless an implicit promise that life would go on, and would be full of surprises. And in her music, as again and again she sought someone who could understand her, who could offer a counterbalance to her ramblings and yearnings, she would tell us not to listen for her but to listen for ourselves. She wanted us to have some sort of transference. It was not a delusion to listen for yourself. It was an injunction.

That said, Joni’s songs taunt listeners into biographical readings, and they also invite us to understand the mind creating them. That’s what I wanted to understand, that’s what I hoped to find out when I first met Joni Mitchell, in January 2007. She had just finished recording her first album of new songs in ten years, Shine, and the Alberta Ballet was in rehearsal with The Fiddle and the Drum, a collaboration between Joni and the choreographer Jean Grand-Maître. I had come to Los Angeles to interview her for The New York Times.

*

It was 5 pm at La Scala Presto, an Italian trattoria in Brentwood. Joni had picked the restaurant because it was among the local restaurants willing to incur fines just for the pleasure of having Joni Mitchell dine and smoke there. As urban centers all over America were banning smoking in public places, life for Joni Mitchell was still a noir film from the 40s, full of nicotine and screwball repartee. She kept smoking in public as long as she could, until she was eventually reduced to e-cigarettes.

I stood at the bar at the restaurant waiting for her, clenching my glass so tightly it broke into little pieces. That’s when they figured out I was the one meeting Joni and told me to relax: she was really nice.

Really. I asked where she liked to sit. The outdoor table with the ashtray, of course. It was unseasonably chilly for LA and I asked them to turn on the heating lamp. I took the seat she didn’t prefer. I had brought a collection of Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy and Nietzsche Contra Wagner, books I knew had inspired Joni’s lyrics and weltanschauung, along with Kipling’s “If,” which I knew she had set to music. I looked to the final stanza, which I later learned Joni did not include in her adaptation, as a mantra to give me strength:

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

I didn’t want the earth or everything in it, and I didn’t think Joni would want me to be the kind of man Kipling was telling me to be, but I thought, if this poem was important to Joni, then I would figure out why.

A half hour late, perfectly on time, a hand studded with more jewelry than I could fully take in reached out to me. “I’m Joni,” she said. “I know,” I replied. Be cool, just listen, and breathe. And listen some more.

None of the wines at La Scala Presto pleased her. She tasted each one. None was smooth enough to suit. Much more to her liking was a 1998 Chateau Margaux she pulled out of a case, later, at home.

She was giddy about the album, and ready to unleash what she calls a verbal “cauldron.” We talked about Miles Davis—about how she was introduced to him by Joni’s drummer boyfriend Don Alias, who had played on Bitches Brew, and about how Miles once made a play for her, then passed out with a deathlike grasp on her ankles. She had always dreamed of collaborating with him, she said, and it was reported to her that he owned all her albums that had been released up to his death. She loved Duke Ellington; disliked Coltrane, but she so loved Kind of Blue that she even liked Coltrane on it. And Debussy, which she pronounced “De-Boosie.” When she heard La Mer, she saw the sea.

Of course we talked about the ballet, and the new songs, which no civilian had heard yet. We talked about environmental apocalypse, about the Indian chiefs with their old beliefs, about the stupidity of Western medicine. “I’m mad at Socrates,” she said at one point. We talked about our shared love of the films of the Serbian director Emir Kusturica; about how she missed the conversations in New York City; about how she loved Dylan’s “Positively 4th Street” and “Mr. Tambourine Man,” and Blood on the Tracks (the New York sessions, not the Minnesota), but that she thought Desire was just okay and that Modern Times, which had just been released and had hit number one, was a work of “plagiarism.” “You can’t rule Bob out, though,” she said. “He and Leonard are the best pace runners I’ve got.” Then she slammed Cohen’s line from “Master Song,” “Your thighs are ruined,” as cruel to an older woman, and declared that even though he walked the walk and had become an ordained Buddhist monk, he was a “phony Buddhist.”

And yet, as hostile as some of this might look in print, it was all delivered with a joie de vivre. She loved to be provocative. She loved to be what she called a “pot stirrer.” She was trouble—and she was really good at it.

We closed the place down. The caravan continued to her house. There was a talking security system at the gate. I looked at her stack of books and noticed Simon Schama’s Rembrandt’s Eyes. Of course, I thought. She’s the great Renaissance portrait artist in song. They go for every nuance, the chiaroscuro of human emotion, the overtones beneath the chords, the resonance of existence.

She was sleeping by day, chain-smoking and creating by night. It seemed like we could have talked forever (and by talking, I mean she did the talking and I did the listening). Even though she is known for her introspective brooding—comparing herself with Job in “The Sire of Sorrow,” and singing lines like “Acid, booze, and ass / Needles, guns, and grass / Lots of laughs”—she actually does like to have lots of laughs. A devastating mimic and raconteur, she can serve up Dorothy Parker–like zingers with terrifying speed.

After twelve hours of Joni, up all night, my sense of reality had been permanently altered. On the flight home, I wanted to somehow keep the experience going, and I started listening to Hejira. The voice I heard was different. In the 1976 recording, I could hear her Saskatchewan cadences, her joys and her sorrows and everything in between.

During the week that followed, our conversation continued on the phone. And then my piece about her was published, and there were things about it that felt to her like an invasion, a betrayal.

I got bitched out by Joni Mitchell! She was a maestro, hurling one indignity at me after another. She loathed the picture the Times had chosen, and there was one phrase in particular that made her gorge rise: “middle-class.” That was the adjective I had used to describe her home. It struck a chord—and not a chromatic one—through the heart of the author of “The Boho Dance,” the art school dropout for whom there could be nothing worse than to be bourgeois.

“I don’t know what you think of as middle-class, but I live in a mansion, my property has many rooms, I have Renaissance antiques.”

“I meant that your home, at least what I saw of it, wasn’t intimidating. It was inviting. It was earthy.”

“Yes, that’s true. You were in the earthy section of my property.”

“Yes, earthy. I should have said earthy. If I could substitute the word now I would.”

She was so disappointed in me. She had thought I was different, somehow better than the others. Now I was the worst.

*

Years passed. One night, I had a delightful time out with a friend of hers, a sculptor who inspired her song “Good Friends” from Dog Eat Dog. Without any prompting from me, he called Joni and told her she had to go back to talking to me, and she did.

I flew to LA to see her. Even under the fluorescent kitchen light, she looked more beautiful than she did in the ads for Yves Saint Laurent that were in all the magazines. She looked strong, resilient, defiant, head held high. Ready for battle.

“You have no attention span,” she snapped.

“I’ve been sitting here for twelve hours,” I said. “In what universe does that mean that I have no attention span?”

I got an idea of what that universe was. I had questions prepared about her music, about art, and we did talk about those things, but she would invariably shift to her emotions, her body, her desires, the desires of men, the impossibility of relationships. At one point, during a wrenching description of a miscarriage, she stopped.

“Why are we talking about this?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I was prepared to talk about the music.” But talking about the music meant talking about everything, because Joni Mitchell’s songs go straight to the heart, to the marrow, to the stuff of life. We weren’t going to sit there for half a day just talking about open tunings, though we did some of that, too.

And she played for me. She clipped her nails and began strumming a sequence of stunning chords. I recognized it as “Ladies’ Man” from Wild Things Run Fast (1982), a song inspired by the notorious lothario David Naylor. I asked her why she’d chosen to play me that. “It was the first tuning I found,” she said. I got up from the chair and watched her play from various angles. There is a picture from 1968 of Eric Clapton looking at her with similar wonder. His facial expression unmistakably said, “How does she do that?” is late in the game, she still had the power to confound. She delivered it once more, to an audience of one. When she was done, I applauded.

A couple of months after our encounter, Joni suffered a brain aneurysm. Joni would need to claw her way back yet again. Nothing lasts for long. All romantics meet the same fate. Albums are like novels or poems except that you can listen to them in the dark. You can always flip the record, put in another CD, reset the iPod. Close your eyes. Joni Mitchell will be there waiting for you.

__________________________________

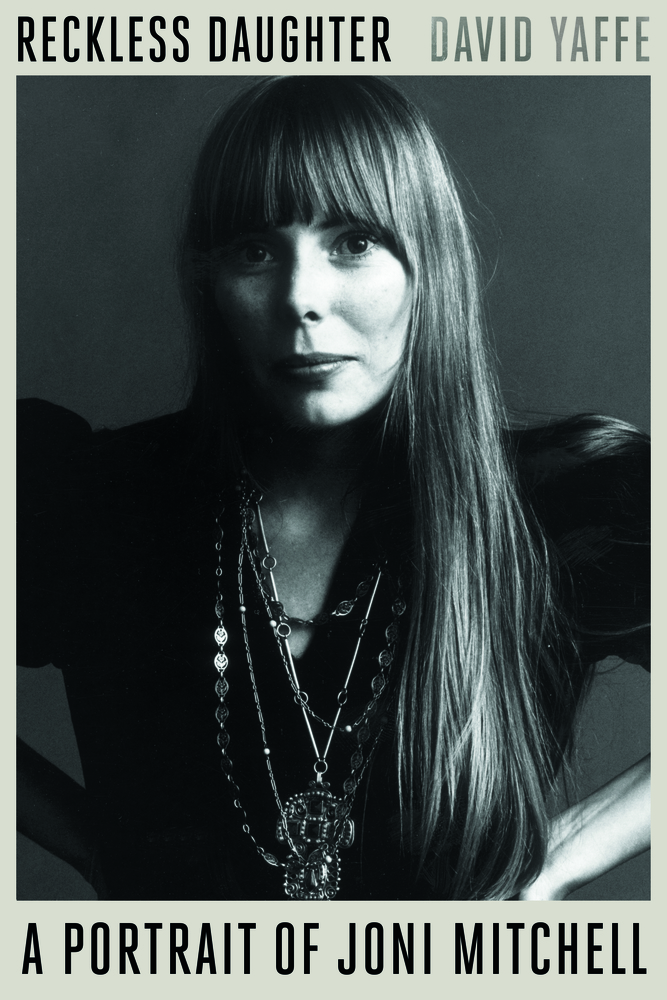

From David Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter, courtesy Sarah Crichton Books. Copyright 2017, David Yaffe.