Musical Storytelling: Librettist Gene Scheer On Transforming Novels Into Operas

Viviana Freyer Shares a Look Inside Two Current and Upcoming Literary Adaptations For the Stage

The marriage between literature and opera has long existed. In the classic repertoire, Alexander Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, and Prosper Merimée’s Carmen inspired Tchaikovsky and Bizet’s respective operas of the same name, and The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas fils became Verdi’s La Traviata. More recently, an adaptation of Michael Cunningham’s The Hours, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, premiered in 2022 at the Metropolitan Opera in New York to great acclaim.

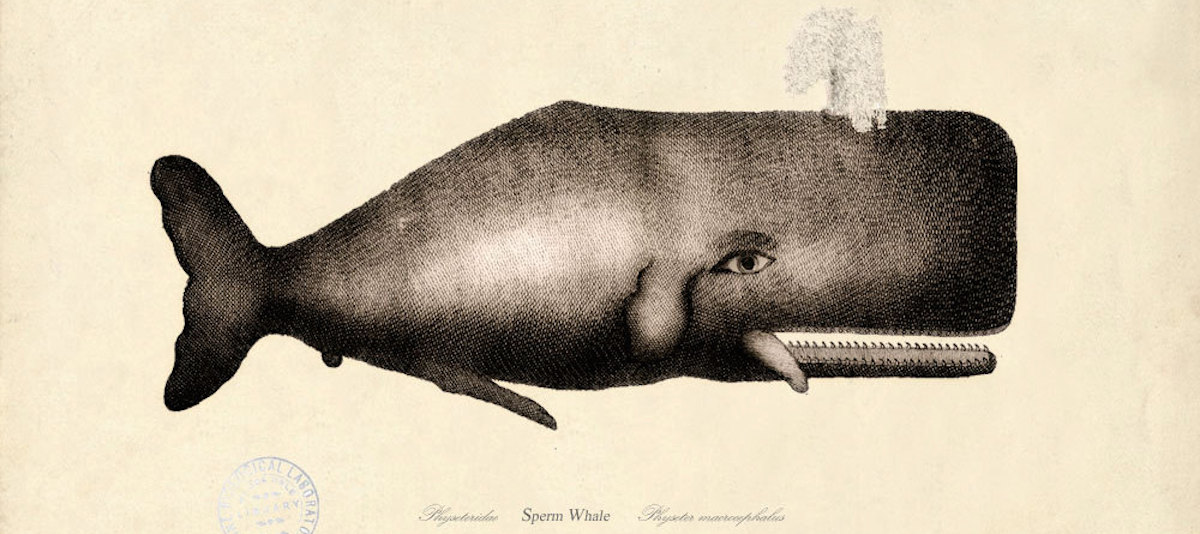

Now, the opera house celebrates the opening of two new literary operas: Moby-Dick runs until March 29th, and The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay opens in September.

Gene Scheer is the librettist who took on the formidable task of turning these beloved American classics into full-on operatic spectacles. Scheer’s work has been sung all over the world, and his operatic adaptation of Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain earned him a Grammy nomination. An avid reader himself, he cites George Eliot and Charles Dickens as among his favorite authors, “I seem to really gravitate towards things that have bloomed out of popular culture,” he says. “[Eliot and Dickens’s books] are classics now, but when they were written, they were things that were written for the general public to dig into.”

In Scheer’s interpretation, it is living out the story of Moby-Dick that turns him into the Ishmael readers know.

Like many readers, Scheer’s first encounter with Moby-Dick was in high school. “[I] didn’t really pay much attention to it,” he admits, “I skipped a lot of sections, [like the] Cetology sections, which are now, by the way, my favorite parts of the book.”

But in 2010, the Dallas Opera planned to commemorate the opening of their Winspear Opera House with a world premiere. Composer Jake Heggie and the late playwright Terrence McNally were originally going to collaborate on Moby-Dick, but when McNally withdrew due to health concerns, Scheer signed on. Upon reading Moby-Dick, Scheer remembers being “absolutely caught on fire with enthusiasm” and immediately recognized its potential for an operatic adaptation.

As for Kavalier & Clay, Peter Gelb, General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera, asked composer Mason Bates to write an opera. Bates suggested the novel after having traveled to Berkeley, California to get Michael Chabon’s blessing to adapt the project. It was the MET who then paired Bates with Scheer, who was already a fan of Kavalier & Clay.

Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel chronicles the early days of comic books and the friendship between Jewish cousins Josef Kavalier and Sammy Clay, whose character The Escapist takes New York City by storm. Like Moby-Dick, it’s a swashbuckling novel that’s equal parts funny, tragic, thoughtful, and moving. In both cases, Scheer had his work cut out for him writing the librettos.

Scheer first spent “a good six months or more” reading the books to “figure out [the] way in operatically.”

When adapting the novels, Scheer had to prime the libretto to showcase music as the central storytelling element. “When you’re reading a book, you have a narrator that can fill in all sorts of details,” says Scheer. In opera, Scheer explains, the narrator is the composer. Music becomes, in his words, “the voice that [carries] the audience member through the story.”

Scheer was determined that the libretto and music of the operas “rhyme” with each author’s voice. In the case of Moby-Dick, Scheer shares the writing credits with Melville himself, whose prose he describes as “dense, rich and poetic.” He says he “sewed together” different passages—principally, Ahab’s monologues—for the libretto, while he himself wrote the rest. “Though, I tried not to make that particularly evident,” he says with a laugh.

In fact, one of the most famous lines from Moby-Dick serves as the catalyst for the opera’s structure: while “Call me Ishmael” opens the novel, it is the last line of the opera. “Moby-Dick is a memoir,” says Scheer. “[Ishmael] is recalling what happened…But in theater, your task is not to tell a story, but rather, to show a story.”

Moby-Dick the opera depicts what Scheer calls “the education of Ishmael,” with the audience experiencing in real time the events on the Pequod along with the characters. In the cast, Ishmael is billed as “Greenhorn,” a decision Scheer made upon the observation that he is the only first-time whaler in Ahab’s crew. In Scheer’s interpretation, it is living out the story of Moby-Dick that turns him into the Ishmael readers know. “…when the Captain of the Rachel says, ‘Who are you?’ and he says ‘Call me Ishmael,’ it’s as if he’s now had the experience, and now he will live to be able to write it.”

The change in structure may seem like a grand departure from the novel, but Scheer is happy to report that Moby-Dick the opera was “really embraced” by the Melville Society and other Melville scholars. One such endorsement comes from Nathaniel Philbrick, author of In the Heart of the Sea. Scheer and composer Jake Heggie interviewed Philbrick, at the start of their writing process, and in a full circle moment, Philbrick will be attending Opening Night.

The value of these stories for Scheer is how they connect with audiences.

The Amazing Adventures Kavalier & Clay became principally an adaptation of feeling, with Scheer using Chabon’s text as “hook lines, or points of departure” as opposed to borrowing direct passages. “There is an experience of fun reading that book,” he says. “The energy of these young guys and their dreams…the text pulses with so much excitement.”

To capture the novel’s expansive scope, Scheer created what he calls “three different worlds” in the libretto that represent the story’s major structural points. Kavalier & Clay begins with Joe’s escape from Nazi-occupied Prague, so the first world has “a musical language [combined with] a black-and-white visual world of what’s happening during the Holocaust.” The next world, what Scheer refers to as the “swing world of the 1940s’,” shows the bright-eyed Kavalier and Clay at work, and consequently, they create the third world of the opera themselves. “They’re creating [The Escapist],” says Scheer, “so the comic book has its own musical language… and the comic book comes to life.”

As the characters’ lives grow complicated and the highs become lows, “the three worlds smash together” and become “a musical and visual representation” of what the characters, namely Joe, feel. “It was, in my mind, an operatic way of doing what Michael did so brilliantly in his book,” says Scheer. “…And I think it’s successful because, in large part, Mason [Bates] has written such incredible music. Mason’s music becomes the thing that really rhymes with Michael’s voice.”

Though critical juggernauts (even if Moby-Dick flopped during Melville’s lifetime), the value of these stories for Scheer is how they connect with audiences. “What I’m trying to do is write pieces that are moving, entertaining, and powerful; [stories that] come out of America and that speak to America,” he explains.

Scheer also hopes Moby-Dick and Kavalier & Clay can serve as introductions into opera for newcomers. “The visuals that both teams have created are out of this world. There’s incredible energy in these stories and there’s great tunes in the telling of these operas,” he says. “And they’re both deeply American stories that an American audience will feel in their kishkes…It’s something that’s very familiar from all of our lives that is now being depicted onstage and in music.”

Viviana Freyer

Viviana Freyer writes about literature and film. She is a graduate of Bryn Mawr College.