Muhammad Ali, Author of "The Greatest Book of All Time"?

The Early 1970s were Hard Times for an American Icon

In the spring of 1970, Muhammad Ali began work on his autobiography, promising, of course, that it would “outdo everything that’s ever been written.”

Random House paid an advance of more than $200,000 for the memoir, assigning one of its most talented editors, Toni Morrison, to shepherd the project. Richard Durham, the former editor of Muhammad Speaks and a writer with a longtime interest in Marxism, agreed to write the book based on a series of extensive interviews with Ali.

“The public doesn’t know too much about me,” Ali said at the press conference announcing his book deal. At first, the remark seemed funny, considering that Ali was perhaps the most widely publicized man on the planet and had been telling his own story virtually without pause since he first gained fame as an Olympian a decade earlier. But how well did the public really know Ali? How well did Ali know himself at age 28? Who was he? What did he hope to become? The questions no longer hung about him in the vague way they hang about most men and women. Now the questions demanded answers in writing.

Was he Muhammad Ali or Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.? It was difficult to say. He had been born Clay and taken the name Ali, but he had never legally changed his name in the six years he had been calling himself Muhammad Ali. The paperwork had been too much trouble. And then Elijah Muhammad had taken away the name, saying that as far as the Nation of Islam was concerned, Cassius Clay was Cassius Clay again. Ali, meanwhile, continued to call himself Ali.

Was he the heavyweight champion of the world? He’d won the title by defeating Sonny Liston and defending it successfully, but boxing officials had stripped him of his crown, saying a Muslim draft dodger was not entitled to be the sport’s titleholder. Yet the champ continued to call himself the champ.

Was he a boxer? A war protester? A leader of the Black Power movement? A humble follower of Elijah Muhammad? Who was he? What did he want? Like others, he wanted money, attention, sex, adventure, and power. He wanted to be special, and he wanted to be seen as special by people around the world, especially black people. “Who’s the champ?” he asked audiences wherever he went. “Who’s the champ?” He repeated the question until the answer came in the form of a chant: “Ali! Ali! Ali!”

Constantly craving attention wasn’t easy. It forced him into endless contradictions. It turned him into a fighter who said he didn’t care to fight, a writer who didn’t write, a minister without a ministry, a radical who wanted to be a popular entertainer, an extravagant spender who said money meant nothing to him, a dietary ascetic who guzzled soft drinks and sold greasy hamburgers to his fans, an antiwar protester who avoided organized demonstrations even when President Nixon’s decision to invade Cambodia provoked the largest student strike in the nation’s history, and a religiously devout and demanding husband who openly cheated on his wife. As the 1970s began, Ali’s desire to be all things to all people would send him on a wild ride as he sought to define himself in his own life, in the public’s eye, and in the pages of his biography.

Fortunately for Ali, the political and social dynamic was changing, and forces beyond his own control also defined him. When he had won the heavyweight championship as Cassius Clay, he had been merely a promising boxer with manic energy and a loud mouth. When he had joined the Nation of Islam, he had become a prominent member of the most radical wing of the black movement in America. When he had refused the draft and been banned from boxing, his position in American society shifted again. Thousands of other draft-age young men followed his example and evaded military service, although most of them did so without risking imprisonment. Some fled to Canada. Others enrolled in graduate study. Those with clout called in favors. Of course, many young Americans lacked the clout and the money to avoid the draft. They didn’t have a team of lawyers to file appeals in court, as Ali had. These young men faced the unpleasant choice of running away, going to jail, or accepting enlistment. Ali was no ordinary demonstrator. Still, as millions of Americans protested the war, the boxer’s actions seemed less treasonous and more courageous, especially among young white protesters. After the demonstrations at the 1968 Olympics and countless other protests by black athletes, the sight of an outspoken black athlete no longer shocked. Mainstream black leaders such as Julian Bond and Ralph Abernathy, who had once disdained Ali, began to cheer him. As other black activists grew more radical, the Nation of Islam seemed less frightening. When boxing officials denied Ali the right to box and the government revoked his passport, even some of the white sportswriters who had criticized the fighter questioned whether he was being singled out unfairly because of his color and his religious and political beliefs. It wasn’t that Ali moved toward the mainstream but that the mainstream moved toward Ali.

Years later, the writer Stanley Crouch would compare Ali to a bear. When he was a newly minted Muslim calling white people devils, Crouch said, Ali was a real bear, deadly dangerous and impossible to control. But as Ali found popularity, the boxer began to behave more like a circus bear, one that flashes its teeth and claws but only threatens harm.

*

In the spring of 1970, Belinda and Muhammad moved to Philadelphia, mostly so Ali could entertain business and entertainment opportunities in New York. In August, Belinda gave birth to twins, Jamillah and Rasheda.

His life in the early months of 1970 lacked structure. He no longer rose early each morning to exercise. His calendar contained few appointments. Ever since Elijah Muhammad had expelled him from the Nation of Islam, Ali had stopped attending Muslim rallies or prayer meetings, although he continued to pray at home several times a day.

Some of Ali’s friends wondered if he would leave the Nation of Islam rather than wait for Elijah Muhammad to grant forgiveness. The Nation of Islam was growing weaker. Huey Newton and the Black Panther Party captivated young black men more than Elijah Muhammad, who turned 73 in 1970 and had begun to lose key members from his inner circle. Accusations of corruption dogged the organization. Karl Evanzz, in his biography of Elijah Muhammad, said that expelling Ali may have been the best thing the Messenger ever did for the boxer. Just as the Nation of Islam was beginning to self-destruct, Ali gained distance from the organization, yet another example of the great luck and timing that had marked his life to date.

When the civil rights activist Jesse Jackson spent time with Ali in the early 1970s, he was struck by the casual nature of Ali’s relationship to the Nation of Islam. Jackson remembered one day when he and Ali visited Jackson’s mother. She had baked cracklin’ bread, named for the fried pork skin that gives the bread its crunch, and Ali dove into it with vigor. Between bites, Ali asked what was in the bread, but Jackson wasn’t fooled. “He knew what was in it!” And did he continue eating it after he was told that the bread contained an ingredient forbidden to Muslims? “He ate a pan full,” Jackson said,

laughing.

In hours of conversation during his years of exile, Jackson never heard Ali express misgivings about the Nation of Islam. At the same time, he never saw Ali with a prayer rug. Why did the boxer remain loyal to the Elijah Muhammad, even as the Messenger’s power waned?

Jackson had a theory: “I think there was always anxiety about what happened to Malcolm.”

Ali was not an active member of the Nation of Islam. He was not a boxer. He was a convicted draft dodger, but even that remained unresolved, as his lawyers continued working on his appeal. It was difficult if not impossible to say when anything would be decided. Yet, even in private discussions with friends, he never expressed doubt about his decision to refuse the draft.

*

Joe Frazier was heavyweight champion now. Although smaller than Ali, at five-foot-eleven, Frazier was a skull-shattering puncher. After beating Ali’s former sparring partner Jimmy Ellis, Frazier possessed a record of 25 wins and no losses. To prove he was still the best, Ali would eventually have to beat Frazier. There was talk of an Ali-Frazier fight in Mexico, then Canada, but Ali couldn’t get a passport. “I have officially retired from boxing,” Ali said after the Canadian fight with Frazier was rejected. “I am busy with my autobiography and they want to make it into a movie. I don’t have a title yet, but I am thinking of— ‘If I Had a Passport I’d Be a Billionaire.’ ”

He continued, “I am a freedom fighter now.”

__________________________________

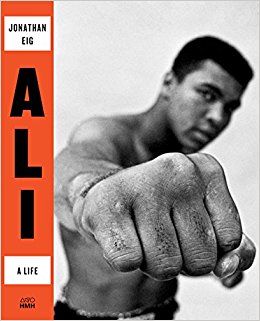

From Ali: A Life, by Jonathan Eig, courtesy Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Copyright 2017, Jonathan Eig.

Jonathan Eig

Jonathan Eig is a former staff writer for The Wall Street Journal, where he remains a contributing writer. Eig has also written for The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, and Slate.com, among others. His first book, Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig, won the Casey Award for best baseball book of the year.