Mothers, Daughters, Lovers: On the Groundbreaking Art of Kathleen Collins

Danielle Jackson Finds Inspiration in Whatever Happened to Interracial Love

1.

In many ways, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? isn’t about interracial love at all. A collection of revelatory, lyrical yet plot-driven pieces of short fiction, it happens to include insights and observations about living in a society where race matters. That distinction is important. The author of the collection, New Jersey-born Kathleen Collins, was a feverishly hard working polymath who died at 46 in 1988. Nina Collins, Kathleen’s daughter, was then 19. She adopted her younger brother, got married, and had four children of her own. For nearly 20 years, Nina kept a trunk of her mother’s papers stored everywhere she lived, but left it unopened. It wasn’t until the failure of her marriage, during her thirties, that she felt an irresistible urge to confront her mother’s work.

When she did, Nina found letters and journals, an unfinished novel of more than 700 pages, several screenplays and stage plays, old family photographs, and many short stories. She assembled and lightly edited some of the most fully formed pieces into a collection and sold it to Harper Collins’ imprint Ecco. Nina named the collection after the 25-page, third person narrative that serves as the collection’s anchor.

Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? includes 15 stories in addition to the title one and was published in December 2016. Many of its protagonists are well-educated black women. They are the kind of women who pepper phrases borrowed from French into already erudite English. They can be prickly and dark, and are often irreverent about their blackness. While there is no blatant self-hate, racial angst abounds, made more complicated by an awareness of class, social status, respectability, and how they all co-mingle. As the unnamed protagonist says in “Stepping Back,”

I’m not trying to flatter myself, but I was the first colored woman he ever seriously considered loving. I know I was. The first one who had the kind of savoir faire he believed in so devoutly. The first one with class, style, poetry, taste, elegance, repartee, and haute cuisine. Because, you know, a colored woman with class is still an exceptional creature; and a colored woman with class, style, poetry, taste, elegance, repartee, and haute cuisine is an almost nonexistent species.

Some of the characters are activists from another era. In May of 1963, Ku Klux Klansman bombed Sixteenth Street Baptist church in Birmingham and four black girls under 15 died in the blast. That August was the March on Washington, and the following summer, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act.

1963 was a turning point, lodged on a precipice of great violence and chaos, but with an optimistic sense that tenets of the movement were starting to take hold. Kathleen Collins had worked on voter registration and speechwriting for SNCC while in college. She set the collection’s centerpiece story “Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?” in 1963, calling it the “year of the human being. The year of race-creed-color blindness.” Visceral details about the drama and bloodshed endured by white and black activists, the youthful rebellion of SNCC and shadows of movement icons like Bayard Rustin form the story’s backdrop. But in its foreground are the relationships between characters—a black woman graduate of a white college and the earnestly idealistic white activist she falls in love with to her middle class family’s dismay.

The couple’s friends are a similarly earnest bunch of multiracial artists and activists living on the Upper West Side. They want to create a world where love and friendship overcomes the strictures of race and capitalism. It feels hopeful as they try, yet also heartbreaking, because all along, it is obvious they will fail.

Collins had a way of going deep into her characters’ heads and hearts. In her stories, she tended towards packing several details of varying dimensionality—sensual scenic details, descriptions of her characters’ physicality, interior voiceovers that capture the chaos within—into a few short sentences. Her writing feels cinematic in detail and scope. It makes sense: she was also a groundbreaking filmmaker whose 1982 feature Losing Ground, about a black woman college professor and the unraveling of her marriage to an unreliable painter, is thought to be the first feature film directed by a black woman.

I discovered Kathleen Collins when Losing Ground screened publicly for the first time, in the fall of 2015. Critics at The New Yorker and the New York Times raved, making note of the main characters’ physical beauty, the lush scenes of saturated colors filmed in the Hudson River Valley, and the palpably tense marriage depicted. The critics were right; Losing Ground was a prodigious accomplishment. Collins’s script showed her ample comedic gifts, and she shot quirky angles that made the film feel moody and surreal. Years before the Cosby Show’s debut or Spike Lee’s first feature, She’s Gotta Have It, Collins was here, mining stories of the black middle class for inspiration.

“I worry about running out of time, that I will die if I do not try as hard as I do. But I also worry that it will kill me, all of the trying.”

Kathleen Collins did not live to see her film’s release or the publication of her stories or the public’s embrace of any of it. Loving her work the way I do, it stings to think of that. I have long held a morbid curiosity about black women artists who died too young, but who, while they lived, were doggedly committed to their artistry despite many odds. Among them: singers Minnie Riperton, Billie Holiday, and Whitney Houston, playwright Lorraine Hansberry, and my paternal grandmother, Tecumseh Jackson, who died when my father was five and had been the only black drama teacher in their small Arkansas town. It seemed their earthly bodies could not sustain the fire of their gifts and the toil against external stressors that threatened to keep them silent. They left us with films and plays and poems and songs yet to be written and sang and directed. When I think of them, or enjoy their work, I must be honest and say I see my own fiery yet fitful desire to tell stories, to make art. I worry about running out of time, that I will die if I do not try as hard as I do. But I also worry that it will kill me, all of the trying.

A year after the first time I watched Losing Ground, and a few months after I’d started wading my way through Collins’ collection of stories, I went to a healer who used sound and reiki to treat my anger. I’d just started a new day job and felt torn about going back to a company knowing how much I needed to spend more of my time writing. And I had recently ended a relationship with a talented painter who couldn’t quite put his marriage to death. My father and I were having ongoing conversations about how I would never get over how he’d left me as a child. So much of the outside world felt unresolved and dangerous, too: a steady stream of headlines about murders of innocent black people—at church, in cars, while running away—added layers to my anger and made me feel dizzy and unsure, sometimes, if in the years since Kathleen’s stories, or my mother’s childhood, or my grandmother’s, even, it had ever gotten easier to be a black woman in America at all.

I grew too anxious to sleep, then too exhausted to write when the day was done. I had spells of vertigo that left me feeling faint and fatigued even after they were over. The healer and I screamed together and welcomed in my ancestor guides and we drank rose water to heal my heart. When the exorcism was over, sadness came. Still, I slept better that night than I had in weeks.

2.

I met Nina Collins at her home on the Brooklyn waterfront during a hectic evening last summer. Nina runs a full house, with teenagers, a large sized fluffy and friendly black dog, and a tanned, jolly-looking Italian husband. Her oldest daughter was filming a web series in the house with a friend from college. “This will be a show about trifling niggas,” she told me, and explained to her mother the difference between nigga and nigger in a voice that said it must have been the 50th time they’d been through this. The chaotic hum of their Brooklyn home, where everybody seemed to have space to be exactly who they were, felt hopeful.

Nina learned of her mother’s breast cancer while she was a student at Barnard just two weeks before she died. Kathleen had been treating herself homeopathically from the time of her first diagnosis, and she’d kept her illness a secret from her two children for five years. Aside from being blindsided and stunned, Nina felt betrayed by this omission, and harbored anger that she did not start to confront until facing the rage-filled ending of her first marriage.

When Nina finally began looking through the work her mother left behind, she realized that the material was, as she says, “barely fictionalized.” She recognized nearly all the characters as family, friends, or former lovers of her mother. It was her parents’ fraught marriage that was portrayed in the twin stories “Interiors” and “Exteriors,” possibly in “Treatment for a Story,” “Lifelines,” and most certainly in the film Losing Ground. She also recognized the melancholy that lingers, coloring interactions between characters, haunting nearly every sentence.

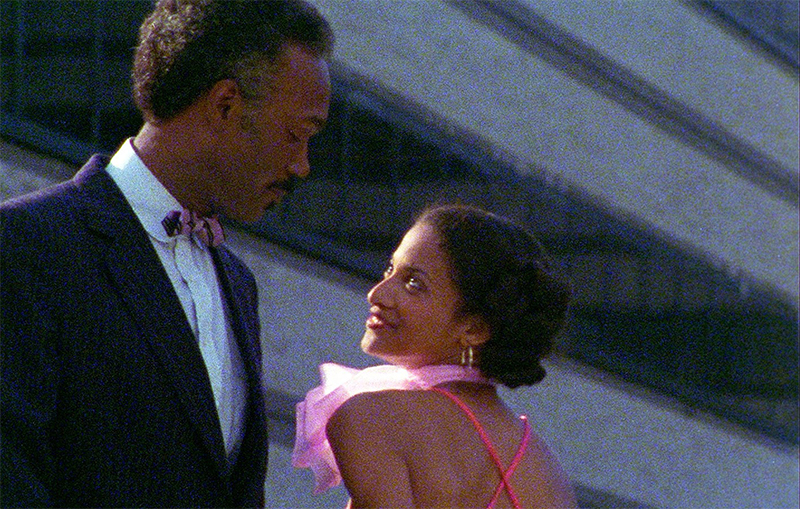

A still from Losing Ground, dir. Kathleen Collins (1982).

A still from Losing Ground, dir. Kathleen Collins (1982).

Nina told me it was often tense growing up. Her mother was preoccupied with the chaos of her marriage to their father, and she worked nonstop on her films and plays and stories, despairing all the while because it was hard to make money. She remembers well the incessant keystrokes of her mother’s typewriter. Nina learned from her mother how to be an artist and, also, how to carry one’s race lightly while still loving it. We talked about the web series “Brown Girls,” and shared the sentiment that it, and much contemporary creative work by or about women of color, strived so hard to be political and purposeful that characters sometimes came out stilted, and humanness, whimsy and interiority got left behind. Kathleen Collins was nothing if not fiercely protective of her inner life. “There is a certain narcissism that she had, that she probably had to have, to accomplish what she did,” Nina said.

Nina has been writing a memoir for nearly a decade that will be about how she became herself, a woman who has faced, head on, the betrayals that made her sad and angry to emerge with a vibrant family life and career she can have at her own pace. “Where my mother ends, and where I begin,” Nina said. While she has been delighted by the public’s belated embrace of Kathleen’s work (she will release another collection of her mother’s writing next year), it hurts that she cannot share it with her mother, and she is eager to move forward with her own projects.

The discovery of Kathleen Collins’ work is a boon for American letters, but it forces questions: What other creative work have we overlooked because it’s stored away in trunks and attics? Who else has been unable to make work that would be transcendent if they could just get it out? I left Nina’s house that night, got a Lyft back to my own Brooklyn apartment and played back the recording of our conversation. I had an early train to make it to work on time the next morning and couldn’t dive into the interview the way I wanted and it worried me. I would have to figure out my own problem of time another day.

3.

A few months after I left the painter, I began going out with a new man, F. I wasn’t exactly in a rush to find someone new, but I’m a Capricorn with the regrettable impulse to do, to expend energy on activity when quiet reflection may be more appropriate. F and I went on many dates in a short time that turned into nights at each other’s apartments. We had mutual friends and a shared, intense love of books. He was Jewish and tall. One evening he took me to see the seminal Killer of Sheep at a Charles Burnett revival. I hadn’t seen the film before, and while I found it beautiful, it was also brutal, with unrelenting images of black pain—stark black and white shots of life in the Watts section of Los Angeles post-rebellion, with aimless children running through ruins and an emotionless, worn down protagonist who cannot make love to his wife. We walked around the West Village after the movie and I felt the heaviness of the film’s despair weighing down on me.

F. talked about how beautiful the film had been. I mentioned, somewhat quietly, that I found it “sad.” I had no desire to belabor my point nor to linger in those feelings. We were having dinner, and we moved on to talk about his time in Cuba, when he got to meet the activist Assata Shakur. He said she was kind, tiny, and more “feminine” than one would expect, given the ferociousness of her story.

“Seeing each other is just something black girls grow up doing every day.”

On one of the early nights of summer, when it was breezy and not yet muggy but still warm, we walked down the streets of historically West Indian and Jewish Crown Heights holding hands, bypassing old bodega storefronts and new trendy but boring bars. A small black girl came up to me, skipping, braids flying behind her back. “I like your dress,” she said.

“Thank you. I like yours.” I told her as she skipped away.

F. was silent after the exchange, but I thought nothing of it. For me it was insignificant, a moment of whimsy. Seeing each other is just something black girls grow up doing every day.

A few days later, it was over with F. He sent me an email about how our cultural differences had made things difficult. “I didn’t know what to do about all the people fawning over you in the street, just from you being you,” he wrote. “It seems like you are black, southern royalty, a queen. And I am no king.”

I had loaned him my worn and highlighted copy of Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? because someone in his writing group recommended it to him. At first he’d thought it was a book of essays about how to navigate interracial relationships, and I tried to explain that it wasn’t that. I said it was “fiction about imperfect black women.” I never got the book back, and I was saddened that by losing him, I was losing it too. But F. had tried to read me like a book, and I suspect he wanted to relate to my blackness more than anything else.

That is hard to do with real, live human beings. Because they surprise you, and live in between categories, and color outside the lines, messily, with their lives.

Danielle Jackson

Danielle A. Jackson is a Memphis-born writer of essays and fiction living and working in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in Velamag, The Rumpus, Blackberry, and Mosaic.