More To Be Shaped By: Searching for Black Nature Writing

Erin Sharkey on Decolonizing the Wild Experience

So much nature writing is about freedom and access to the vast spaces that provide crisp air and opportunities for fresh perspectives. But this collection’s origins lie in a revelation that came to me while teaching nature writing in a prison setting, where participants didn’t have access to such liberative experiences. I began teaching in prisons in 2016, after years of activism in response to the violences of the “injustice” system.

I’d always preferred teaching in nontraditional classrooms and found that the best education happens between students across differences, whether in race, age, or socioeconomic experience. This is exactly the kind of teaching that happens in prison classrooms. And beneath this motivation, I felt an unanswered desire to understand my long-absent father, who was incarcerated for a time when I was a child.

I taught classes from memoir to lyric essay in prisons before answering a call for a new class offering and proposing a fifteen-week nature writing class for Minnesota’s largest facility, a former mental hospital in the southern part of the state. I began teaching in the waning days of summer.

During the class, we marked the way nature transcended the walls of the institution. On the first day, a blaze-orange fox ran across our path to the education building. Over the length of the course, an old-growth aspen grew unbounded, peeling its curling bark, shedding its browning leaves, holding the first Snowflakes on heavy branches.

The writers moved through their days on a schedule imposed by a crackling voice over a loudspeaker, but they also watched birds gliding freely past the windows; industrious yellow jackets throwing their bodies against the glass; and a flock of mallards who navigated puddles in the yard, ignoring the guards watching from their towers. The course spanned the entire fall, from September, when the light stretches long into the evenings, to December, when the students craned their necks to mark the waxing moon as they made their way back to their units.

I learned that nature is not a place where you can escape the oppressive rules of race.

Students remembered summer trips out West, cliff jumping in Oregon, dust storms while serving in the military, working the farm as boys, and favorite winding riverside drives. Nature was a meeting place for writers with very different backgrounds: they were Black and white, Hmong and Anishinaabe. Some grew up in the city, some in the country, some on the reservation; some were from Minnesota, and some were from faraway places.

Over those weeks, the 15 students remembered nature’s power to teach us about ourselves, to help us connect with others, to mark time and its passing, to (re)gain perspective. And I learned from them that nature can shape our lives, even in unnatural conditions like those experienced by the incarcerated. Even in those confines, nature was present and worth observing.

*

I grew up in the Twin Cities, between St. Paul and Minneapolis, the city of lakes. I shook sand out of my shoes nearly every evening of the summer, evidence of days spent on the city’s beaches. A golden tan bloomed on my brown skin, my nose and forehead freckled. I marked years this way. Summers were like this: kids from our southside United Methodist church crammed into a retired Bluebird bus, learning about the Bible and praising Jesus in nature under high pines and on the shores of the state’s ten thousand lakes.

The fall: a blaze of red and orange, tornado drills. The spring: lilacs and lilies of the valley. Floods. The winter: dozens of varieties of snow, knowledge that the coldest days are the ones with the clearest, widest skies. All of this was natural.

Each summer of my childhood, my family loaded up our maroon minivan and embarked on a road trip. The varied landscapes of North America flew by my window in a blur. For weeks at a time, we made our home in a clearing, slept in our big, gray, five-person Columbia tent, and set up our kitchen and dining room on a long picnic table and around a firepit in plain view of our new temporary neighbors.

This public expression of our familial cadence, out in the open, welcomed questions about our racial makeup—two white parents, my mom and my stepdad; my towheaded little brother; the baby, adopted from Guatemala; and me, a big-boned, mixed-race, Black girl. Across the nation, I met other kids, exploring the woods and lazy streams, in national parks and wildernesses. They were white and curious. The inescapable questions—“Are you Black? Why aren’t you with your real parents?”

I learned that nature is not a place where you can escape the oppressive rules of race. I learned that I had access to natural spaces because of my parents’ privilege and resources, their jobs as a teacher and a bureaucrat, their time off in the summer, their own experiences with travel as children. And because of their race, which granted them comfort in the wilderness, in spaces like those campgrounds, in rural areas of this country.

*

In my prison nature writing class, we started with the basics.

Born in the eighteenth century, nature writing grew out of an effort to describe and categorize the attributes of birds, animals, and insects—a list that grew as more of the world was “discovered.” This discovery was violent because it was a tool of colonization, with “explorers” conquering new land and, with it, nature that was unfamiliar to them. Natural history museums also flourished during this time; they often featured human specimens, particularly Indigenous peoples, as well as plants and animals.

The grave-robbed remains of twenty-two Inuit endured in the archives of Chicago’s Field Museum until 2011, when they were returned to the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami in Labrador. The San Diego Museum of Man displayed human remains until 2012. The hierarchy of colonization is reproduced within natural history, in the sorting of some humans as subjects rather than scientists. The work of empire, conquering and cataloging, is the field in which nature writing emerges, making its appearance in response to conditions of the state: industrialization, capitalism, urbanization, democracy.

One of the trademarks of the genre is that it is rooted in first-person observation, so it is vital to investigate the identities of those observers. Let’s consider Henry David Thoreau, one of the central figures of the field. Before Thoreau set out to live deliberately, he had ample leisure time and resources to imagine the Walden Pond project.

He embarked on Independence Day of 1845 for the two-year, two-month, and two-day experiment; he had just been released from a brief stay in jail, having been arrested for failure to pay poll taxes in protest of slavery and the Mexican-American War. His debt was paid by a family member. The land his cottage was built on was owned by his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson. (Students in the nature writing class noted the similarity of Thoreau’s 10′ by 15′ cottage to the size of the cells they occupied.)

And the genre remains dominated by white, cisgender men with access to resources. Thoreau’s Walden was followed by Audubon’s trees and Darwin’s finches, which were then followed, over the following century, by Burroughs’s trout, Leopold’s gray owl, Abbey’s desert, and Pollan’s farm. Men who moved toward conservation. Their female counterparts considered nature and the body. Rachel Carson, Terry Tempest Williams, and Annie Dillard invited readers to consider the environmental impacts of development and the ways our spirituality can form in relationship to nature. Just as the ways we experience nature in this country are not isolated from our identities, nature writing is not neutral.

Black folks have been instrumental in the stewardship and care of the land, and though their labor has often been carried out under poor conditions.

Nature writing is rooted in the American experiment (think independence, innovation, Western expansion), but who is left out from the canon just above? A collection addressing the presence of Black people and their contributions is itself a distinctly American project. Despite efforts to the contrary, Black Americans’ relationship to nature has persisted from the Middle Passage, when our ancestors traveled the westerlies in the bellies of ships, and from our toil in the fields and the intimate domestic spaces of white families.

It has persisted beyond the state’s continued barriers against Black people building positive relationships to natural spaces. It has persisted beyond Jim Crow laws that legislated violence impeding free movement along the scenic highways of the South. And it has persisted beyond redlining, which relegated Black communities to areas of disinvestment, near toxic, smelly uses like waste storage and industrial manufacturing, that come with a myriad of environmental and health consequences, including asthma and lupus.

These circumstances do not mean that Black people don’t have a relationship to nature. On the contrary, Black folks have been instrumental in the stewardship and care of the land, and though their labor has often been carried out under poor conditions or in service to land not under their ownership, skill and innovation has been evident in their relationship with it. In her book Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors, Carolyn Finney writes that though her parents cared for “someone else’s land for fifty years,” though they “knew more about the land than the actual owners,” they would never own the land themselves.

I am grateful to the earlier books, writers, and editors that have begun the work of documenting these relationships. The list of such books is fortunately getting longer all the time, but two served as inspiration for this collection. The Colors of Nature, an anthology of essays about nature by people of color and edited by Lauret Savoy and Alison Hawthorne Deming, illustrates that nature is a complex concept to navigate for people of many different ethnicities and cultural identities, underscoring both the ubiquity of white supremacy and the ways nature and discussions of power and land underpin the design of this nation. And Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry, edited by Camille Dungy, is a gorgeous anthology that makes the case that Black poets push the boundaries of nature writing beyond the agrarian and the wild to the political, the historical, and the radical. This project would not be possible without such footsteps to follow.

*

In class, I asked students to not simply tell stories that were set in nature but to consider what those stories mean in the greater context of their lives or the larger world. This created a kind of network of meaning, connecting stories with wildly different subject matter and particulars by way of deep themes and significance.

Each essay featured here is linked to an archival object, whether by geographical connection or some relationship of subject matter. My own journey in archives started in 2016, at the tail end of my MFA journey, when I was invited for a few months to explore the Archie Givens, Sr. Collection of African American Literature at the University of Minnesota. I had never had such an opportunity before, to explore without a specific goal in mind, to let one object lead me to the next, to find my own way to meaning.

The Givens Collection lives in the Andersen Library, which has an outward face—a whisper-quiet reading room with oak tables occupied by people hunched over their own investigations—and a private face—a cold cavern, at the bottom of a long elevator ride, filled with a small city of floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and a special alley devoted to Black literature, music, art, and ephemera.

The viewer has an opportunity to connect objects across time, to find connections, to follow thin strains to something the collectors perhaps did not intend.

My curiosity took me from garden club attendance rolls and cookbooks to maps of rural Mississippi and the narratives of people formerly enslaved there—and to a little emerald-green brochure about sharecropping, titled “Farmers without Land.” Published by the Public Affairs Committee in 1937, the short volume discussed the failure of the land-use model, the environmental effects: soil depletion, boll weevils, and soil erosion, as well as poor living conditions and fewer community contracts.

Right away I wanted to know what a boll weevil was. Research told me: they were beetles, hungry for the bud of the cotton plant, who laid their eggs inside and turned the cloud-white bloom into a slimy green mess, decimating crops across the South. The brochure noted that the tenant farming model was also failing because Black growers were migrating to the North.

I learned that looking at archival items requires a particular kind of curiosity because the significance is found not only in individual objects but in their assembly. The viewer has an opportunity to connect objects across time, to find connections, to follow thin strains to something the collectors perhaps did not intend. This is especially true when looking at the collections of items significant to Black history, because they have been shadowed and suppressed by the white supremacy and racism of institutions that collect and store collections. It wasn’t until 2016, with the Smithsonian Institution’s opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, that a federal institution was founded to celebrate the contributions of Black Americans.

The museum had been in development since the days following the end of the Civil War. At a public presentation in April 2016, at a symposium at the African American Museum in Philadelphia titled “Shifting Narratives: Rethinking the Past to Understand the Present,” the NMAAHC associate director for curatorial affairs, Dr. Rex M. Ellis, noted that a great deal of the work of assembling that collection was in working with families and church communities to acquire objects of significance that had never been on display because of distrust in institutions and concern for the respect due them.

Before I had even scratched the surface of the Givens’s physical collection, I learned of a new project at the University of Minnesota: Umbra Search African American History. Named for the darkest part of the moon’s shadow, Umbra aims to provide broad, searchable access to digitized materials in those collections of Black memory. The search tool aggregates over 650,000 items (a relatively small amount) from small collections, archives of all kinds, and institutions across the country.

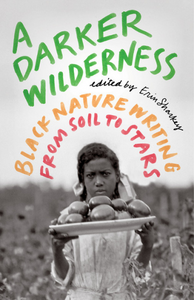

Some of the archival items featured in this anthology were located in Umbra. I stumbled upon the image featured on the cover of this collection using the search term “garden clubs.” I was drawn to the photograph by Bernice Wright’s gaze, direct and not seeking approval as she presents the fruits of her labor. The image description tells us only her name, that she was a member of a homemakers’ club, and that she holds a dish of tomatoes grown in her garden in Caroline County, Virginia. That we have even this information is lucky.

Although it is accessible because it has been digitized, the physical object is housed in a special collection at the University of Virginia and was donated in 1948 by the daughters of the photographer, Jackson Davis. According to his biography, he took over 6,000 photographs documenting the conditions of rural Negro schools in the South.

*

Maybe searching in such an archive is about looking for oneself. An archive can serve as collective memory, though it is important to remember that the archive is not a full or neutral record. Each archive tells a story about the archivist as well as what is archived. The racist structures in place in the institutions of memory can be discerned in the archive, as can the absence of Black archivists within those institutions.

One feature of an archive of Black memory is that it must, by necessity, include many items connected to unknown or unidentified makers and subjects. This project claims and reacquaints the unknown by connecting those makers and subjects to contemporary Black thinkers across time and, in turn, rewrites the record.

The essays in the new anthology, A Darker Wildness: Black Nature Writing From Soils to Stars, reflect a range of experiences with nature, some green and budding, some rusting and tired. Some pieces are positive, some negative, as varied as our various relationships with nature. The authors have reflected on the experience of living through the last half of the twentieth century and the dawning of the twenty-first while weaving those narratives with objects, some from family photo albums and some which date back many generations, to the earliest days of this nation. From a statue erected in a town square to ephemera like travel pamphlets, the items you’ll find range from public and civic to private and personal.

It is my hope that A Darker Wilderness will push the limits of readers’ definition of nature by reintroducing them to historical figures such as François Makandal, Benjamin Banneker, Audre Lorde, and Austin Dabney. By meandering the typography of this country, from Martha’s Vineyard to Detroit, Alabama to Buffalo, Harlem to Antigua, and Alabama to Good Hope, Georgia. By finding meaning from the forest to the ocean, the mountains to a small fishing hole in Kansas, the soil to the stars, the Grand Canyon to the micro-movements of a wasp.

__________________________________

Adapted from A Darker Wilderness and published with permission from Milkweek. Copyright © 2023 by Erin Sharkey.

Erin Sharkey

Erin Sharkey is the cofounder, with Junauda Petrus, of an experimental arts collective called Free Black Dirt and is the producer of Sweetness of Wild and Small Business Revolution. Sharkey has received fellowships and residencies from the Loft Mentor Series, VONA/Voices, the Givens Foundation, Coffee House Press, the Bell Museum of Natural History, and the Jerome Foundation. In 2021, Sharkey was awarded the Black Seed Fellowship from Black Visions and the Headwaters Foundation. She has an MFA in creative writing from Hamline University and teaches with the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop.