More Than Just a Toy: What an Old Dollhouse Taught Me About Storytelling and Family

Elise Hooper: “In a world that feels increasingly troubling and out of control, the dollhouse is where my mother and I are at our best together.”

My great grandmother first received the dollhouse from a family friend, who built it for her in the late 1800s. The dollhouse was then passed down to my grandmother, then my mother, and then me. I was seven when I discovered it underneath the tree on Christmas morning. Even at seven, I understood the dollhouse was more than just a toy. What I didn’t yet understand was that this family artifact would later provide a critical lifeline to my mother.

For me, the dollhouse was never about playing with dolls. In our suburban Boston home, my mom set up a sewing area in a walk-in closet. Surrounded by hangers filled with my father’s dark suits and my mom’s floral sundresses, I sat at her Singer sewing machine, my toes barely reaching the presser foot.

My mom leaned over me, her hands on mine, gently guiding small bits of blue calico under the needle to create dollhouse bedding. She also taught me to knit, so I could produce even more tiny blankets. When my yarn knotted or I dropped stitches, she remained patient and corrected my mistakes, comforting me when frustration drove me to tears—which was often.

I understood the dollhouse was more than just a toy. What I didn’t yet understand was that this family artifact would later provide a critical lifeline to my mother.

When I decided the dollhouse needed art on the walls, my mom gathered old Yankee magazines and a jar full of buttons to show me how pictures could be cut out and glued to the middle of the button, so its plastic rim looked like a frame. She assembled a pleated plastic toothpaste cap, a marble, and a dime, and we glued the pieces together to resemble a miniature lamp. With a little paint and glue, my mom demonstrated that anything could be turned into dollhouse furniture. I learned to look at the world as a place of possibility.

I spent hours of my girlhood sitting in front of my dollhouse, murmuring made-up stories, and creating miniatures, but eventually field hockey practice, play rehearsals, and homework consumed my time outside of school. The dollhouse moved to the attic.

Over the next 40 years, I moved from Boston to San Francisco to Seattle. When my first daughter was born, my mom held my right hand in the delivery room. A year and a half later, my parents relocated across the country to live only five blocks away from us. One summer evening, after my second daughter tripped on our front stairs and cracked her chin open, it was my calm mother who drove us to the emergency room, murmuring assurances the entire time that everything would be fine. And for many years, it was.

With my mom living nearby and eager to spend time with her granddaughters, I had time to be creative. The storytelling skills I’d practiced with the dollhouse evolved into novel writing, and I developed a new career as an author. More years passed. After finishing the manuscript for my fourth book, a story about the hardships and heartbreak of war, I cleaned my desk of the detritus that always accompanies the final push of meeting a deadline—notecards, old photos, books, empty coffee mugs, and chocolate bar wrappings—and my gaze caught on my old dollhouse sitting on the floor of my office.

My two daughters had inherited it, but they had moved onto other pursuits as I did at their age, leaving me to use the dollhouse as a small bookshelf. I studied the antique, noting its chipped exterior paint and faded, peeling wallpaper. This was the fall of 2020: due to pandemic restrictions, I couldn’t travel to research a new story idea, so I sat at my desk, staring at the old dollhouse, remembering the hours I spent with it.

There’s a long, rich history of people turning to miniatures to find comfort and control during difficult and uncertain times. 2020 was no different. I wasn’t alone. With the assistance of modern technology—specifically 3D printers, laser cutters, and Instagram—people were making the most of their time stuck at home by creating beautiful modern dollhouses and miniatures and sharing their work on social media. As I combed through their posts, I was inspired. It was time to update my old dollhouse. I got to work. During the mindless hours of sanding and painting, I listened to audiobooks about the history of dollhouses. While I waited for glue and paint to dry, I’d turn to my laptop to do more research.

I learned that dollhouses were not invented for play. At first, they were status symbols. In 1504, Albrecht the V commissioned an elaborate dollhouse to show off his wealth and women soon followed his lead. In the wake of World War I, after England had lost an entire generation of young men in Belgium’s trenches, Queen Mary turned to the country’s finest artisans and commissioned a four-story grand dollhouse with running water, electricity, and even an elevator. Why? To buoy her nation’s sagging spirits. Impressively, her plan worked: in 1924 over a million people turned out to view Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House exhibit. Dollhouses weren’t produced as toys until mass manufacturing became standard after World War II.

Of all the interesting miniaturists I read about, I couldn’t stop thinking about one: Frances Glessner Lee (1878–1962). She was a Chicago heiress with a peculiar combination of interests—miniatures and forensic science. With ample resources at her disposal, Lee created the Nutshells of Unexplained Death, a collection of dioramas that each portrayed a miniaturized grisly crime scene intended to help train law enforcement agents to solve crimes. All the clues needed to answer the mystery of what happened in those crime scenes resided in the dioramas. But my next book wasn’t going to be about Frances Glessner Lee’s Nutshell Studies—though the concept of a dollhouse containing clues about its previous owner’s life captivated me. I wanted to create a world where dollhouses solve mysteries, a novel in which art saves the day.

Miniatures share a lot in common with writing a novel: they both require patience, focus, and an ability to observe nuance and detail.

The truth was I needed art to save the day. My mother was slipping away from me—it had taken me awhile to pick up on her symptoms, and my father claimed nothing was wrong. But it was. Alzheimer’s. As her memory grew worse, conversations with my mother grew difficult. Repetitious. Confusing. Frustrating. One day when I brought up the sadness I was feeling about my older daughter heading to college, my mother laughed nervously, but said nothing.

I’d later read that empathy can be lost by people with Alzheimer, but the facts didn’t help. I could no longer count on my mother to act like my mother. When we were together, we stuck to superficial, benign topics. I found myself recounting the basics of my day. The weather. The dog. The one topic that we could discuss with any genuine joy was my renovation of the dollhouse. She loved to recount its history, old memories safely out of range of her illness. My mother didn’t find it peculiar at all that her nearly 50-year-old daughter was restoring the old family dollhouse.

Once it had been cleaned up with fresh paint and wallpaper, I embarked on furnishing it, both by updating the old chairs, tables, and beds that had been passed down and by creating new ones. I took a woodworking class, and my confidence with tools grew. One weekend, during the summer of 2021, I built a tiny Art Nouveau bar cart, using a kit I’d bought off Etsy. As I held my completed creation in my palm and showed it to my mother, I realized that miniatures share a lot in common with writing a novel: they both require patience, focus, and an ability to observe nuance and detail. These two creative endeavors balance each other in a way that’s profoundly satisfying.

My mom has no recollection that I’d been restoring the old family dollhouse as part of my book research. In fact, she has no idea that I’d been writing a book. She just thinks the dollhouse is fun and beautiful. And it is. In a world that feels increasingly troubling and out of control, the dollhouse is where my mother and I are at our best together.

__________________________________

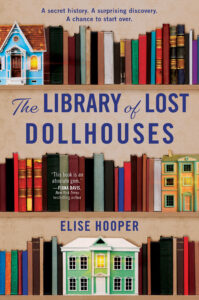

The Library of Lost Dollhouses by Elise Hooper is available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Elise Hooper

A native New Englander, Elise Hooper spent several years writing for television and online news outlets before getting a MA and teaching high-school literature and history. Her debut novel The Other Alcott was a nominee for the 2017 Washington Book Award. Three more novels—Learning to See, Fast Girls, and Angels of the Pacific—followed, all centered on the lives of extraordinary but overlooked historical women. Her next book, The Library of Lost Dollhouses is inspired by a dollhouse that’s been in her family for five generations. Elise lives in Seattle with her husband and two daughters.