More Than Just A Pretty Face: On the Multifaceted Marianne Faithfull

Elizabeth Winder Considers the Women Behind The Rolling Stones

Marianne Faithfull met the Rolling Stones at a Decca party for Adrienne Posta in March 1964—a time when she was, admittedly, “very pretentious about pop music.” Instead of poring over copies of Jackie and swooning over Cliff Richard like a normal seventeen-year-old, she worshipped Paul Valéry, Marcel Proust, and obscure cabaret artists of the Weimar Republic. That was Marianne—not just precocious but from another dimension, in her own rarified world.

Whatever her louche, esoteric world was, it certainly wasn’t this—an industry launch swarming with slick, sleazy managers and would-be pop chanteuses in baby-doll frocks, gobs of mascara, and trendy falls, desperate for a single or a contract with Decca. Braless under her boyfriend’s blue button-up, her blonde hair loosely tangled, she clung to the arm of her new man, John Dunbar, a gallery and bookshop owner who sold rare books and art to Paul McCartney.

All four Beatles were there, and so were the rambunctious Stones, pranking around like “spotty schoolboys.” They were nothing to her Cambridge-educated, bespectacled John, whose tailored pants and artfully disheveled waves put Keith’s ill-fitting leather jackets to shame. Mick was in the midst of a flaming row with Chrissie, who was sobbing her way toward a modish meltdown, tear-drenched lash strips dangling halfway off her lids.

Nearly everyone at the party was drunk—at least half were there for the free booze alone. They barreled around shoving each other, slurring too loudly and hovering too close, their faces sweat-slick and pinked from cheap beer. Desperate for a little space of her own, Marianne wove her way through the crowd and perched atop a space heater. “My God,” she thought. “What awful people.”

One man, however, did intrigue her. Andrew Oldham, the Stones’ flamboyant manager with his silky ties, campy drawl, and neon-green eyeliner. The feeling was mutual. He marched right over with his characteristic pomp and announced, “I’m interested in you—you have a contemporary face. You are today.”

Marianne didn’t know what to make of him, “beaky and birdlike,” lurching toward her one second, then whirling around to address her boyfriend, as if she couldn’t hear or speak.

“Who is she? Can she act? What’s ’er name?”

In a sea of uniformity and fluff, Marianne was an intellectual misfit.

“I can make you a star,” he blabbered, his pancake makeup beginning to melt, “and that’s just for starters, baby.” The fawning was flattering, but this seemed more like the ravings of a self-satisfied drunk. Marianne dismissed his blather, and John drove her back to her mother’s house in Reading. One week later the telegram arrived—and an attached Decca contract. Thanks to Marianne’s youth, a work permit had to be signed by her mother—Baroness Eva Erisso. Eva eventually signed the permit, on the condition that Marianne would be chaperoned on tour.

Andrew’s version was crude: “I saw an angel with big tits and I signed her.” But his boasting vulgarity belied real possibilities. Like all modern iconoclasts, Marianne broke the molds of her current zeitgeist. She was of her time yet far beyond it. Though still a teenager, she was as far removed from the gum-snapping youth-quakers as Lady Guinevere herself. There was something misty and regal about her, like she’d been wandering the forests of Brocéliande. Andrew knew how well she’d translate onstage—standing stock-still the way the nuns taught her. So he locked Mick and Keith in his kitchen overnight, with instructions to write Marianne a song—a song with doves and high convent walls, laden with chaste longing.

Fiction wasn’t far from fact. Marianne had spent the last several years behind convent walls. Her time at the convent was much like Emma Bovary’s Ursuline education or Anne Boleyn’s years in France. The nuns taught her everything—singing, piano, classical dance. Her talented music teacher coaxed out a husky mezzo-soprano wise beyond her years. She joined an amateur theater group and dreamed of playing Ophelia, Cordelia, and Desdemona at the Royal Court.

Marianne planned to be known, but a pop princess career was the last thing on her mind. She’d be an artist of some kind—she’d go to Cambridge, or the Royal Academy of Music to continue classical singing. She idolized the young Vanessa Redgrave, who once came to talk to Marianne’s theater group. Perhaps Marianne would also play Rosalind, or Imogen in Cymbeline, or even sing Tosca in Covent Garden. Awake long in the night in her convent room, she bent over her workbook, filling page after page of potential stage names, pen names, fantasy names. In time she would realize her real name was her own.

Mick and Keith’s assignment was cool and clear pop. Though they barely knew her, the song evoked Marianne herself—wistful, sweet, and vaguely tubercular. It was gorgeous, haunting. “That a song of such grace and sensitivity was recorded by two twenty-one- year-olds was astonishing.”

“They mixed it then and there, and that was it.” It was recorded in thirty minutes. Marianne recalls being strangely let down after the session, eerily aware that she was nothing but a pretty product to them, a gorgeous means to advance their own creative paths. It’s not that they were rude, but there was something crass about the way they ignored her, like boorish schoolboys turned into equally boorish rockers. “Nobody paid attention to me. It was like I didn’t exist, they were so excited… After the session Mick and Keith gave me a lift in their car to the station. Mick tried to get me to sit on his lap… What a cheeky little yob, I thought to myself… I wasn’t a person to them; I was a commodity that they had created. That’s what Andrew liked doing, and he was very good at it. I was a hunk of matter to be used and discarded.”

The recording session stood out like a bad omen. But the song, “As Tears Go By,” with its melancholy sweetness and French jukebox flair, was a sleeper hit, shooting up the charts that autumn and launching Marianne’s singing career. Before long she’d left the convent, abandoned her O levels for record contracts and Ready Steady Go! She fit easily into the songbird cliché—a popular representation of early womanhood characterized by heavy makeup and songs of subtle desperation. It was the first song Jagger and Richards wrote together.

But Marianne, as Andrew anticipated, put her own unique spin on the look. Lulu wore Mary Janes and knee socks—as did half the dolly birds who flocked the Carnaby Street shops—but on Marianne you actually believed it. It was like she’d been wearing them all day, daydreaming in a classroom, elbows propped on a book. Not a hasty costume change backstage at Top of the Pops.

Petula Clark wore nightgown dresses too, but only Marianne could make them look authentic, standing at the microphone like some grave Flemish angel. She wore bell-shaped frocks like everyone else, but in sensual textures with unexpected trimmings, a layered confection of sheer lace. On Marianne, the flute-shaped flutter sleeves suggested something else—a christening gown, a baby’s bonnet, or a sixteenth-century courtesan.

Like most British pop acts in the mid-1960s, it was Marianne’s contractual duty to join national bus tours. They were a charming mix of Merseybeats, Europop, and American doo-wop, hitting various locations throughout the UK. She first toured with the Hollies and Freddie and the Dreamers, as a means to her own flat, her own grin money, her own bank account.

But was this really freedom, cramming herself on a bus, eating cheap food, and enduring smarmy come-ons? In a sea of uniformity and fluff, Marianne was an intellectual misfit, lugging around copies of Tolstoy and the complete works of Shakespeare. She threw up backstage before each performance. One hotel room after the other, no sleep, no food, “flirting with drugs with a copy of Jane Austen on my knee.”

She dealt with the trials of touring by treating the whole thing as a sociological study. The Kinks were moody and gothic, with resentful family dynamics. Roy Orbison was “large and strange and mournful looking, like a prodigal mole in Tony Lama cowboy boots.”

Little did Andrew know, Marianne would be the one corrupting the Stones.

Though young and naive in some ways, Marianne knew from the start this image was forced on her by corporate men. From the very beginning, starting with Decca’s press release for her first hit single: “Marianne Faithfull is the little seventeen-year-old blonde…who still attends a convent in Reading… daughter of the Baroness Erisso… She is lissome and lovely with long blonde hair, a shy smile and a liking for people who are long-haired and socially conscious.”

Convent school, implied virginity, aristocratic lineage, and blonde blonde blonde, the themes had been stacked against her from the very beginning, thrown down like a gauntlet. She longed to escape, like the sparrows and wrens in her mournful pop ballads. “There’s a part of me that always wants to fly off, to escape. That’s what drew me to ‘This Little Bird.’ The words are from Tennessee Williams’s Orpheus Descending. It’s that famous speech about the bird who sleeps on the wind and touches the ground only when it dies.”

The photo shoots, the makeup columns, the requisite inquiries about boyfriends and family, all those expectations of how a female pop star “should” behave abounded. On top of all this there was bossy Andrew, who would call before interviews with specific instructions, down to what to wear. (“Wear the white suit, but lose the boots. No hat, try a scarf. Ciao.”) This piqued Marianne’s contrarian nature, so she began to play little games with reporters.

“I don’t give a fig whether I’m a success as a singer. In the pop business, talent doesn’t count.”

“Andrew’s different. He’s sincere. Well, he says he is, so let’s pretend he is.”

Or: “I believe in living on several different planes at once. It’s terribly important, don’t you think?”

After an interview with Record Mirror on a bench in Kensington Gardens, she’d run breathlessly after the bewildered journalist, waving two volumes of Big Ben by A. P. Herbert. “You simply must try this,” she’d purr in lusty mezzo-soprano, her eyes widening behind bug-eyed horn rims, clutching a worn-out copy of Bitter Lemons to her chest.

“I gave them not only the acerbic, aphoristic Marianne but the dotty daughter of the Baronessa as well… This projected an eerie fusion of haughty aristocrat and folky bohemian childwoman. It was a tantalizing ready-made fantasy. Unfortunately, it wasn’t me.”

Andrew prepped journalists with frilly bite-sized images. Some were accurate—“Marianne digs Marlon Brando, Woodbine cigarettes, poetry, going to the ballet, and wearing long evening dresses.” But most interviews began with references to St Joseph’s school, tales of singing folk ditties for pocket change in local coffee bars, and most importantly, “Mummy,” the mysterious Baroness who hovered over her like a duenna. Her music was described as girly-folk, commercial in a good way.

Marianne herself was “shy, wistful, waif-like,” a “self-styled angel blonde.” Close-ups of her snuggled in bed with blankets and teddy bears, one shoulder glowing bare, but cheeks flushed like a child just roused from her nap. Their articles were littered throughout with nods to Andrew, or “Loogy” as they called him on the beat scene. And always, inevitably, the Rolling Stones.

“Would You Let Your Sister Date a Rolling Stone?” That was rapidly becoming the Stones trademark—schoolboy anti-charisma incited by Andrew. He delighted to feed the press copy like this: “They look like boys any self-respecting mum would lock in the bathroom. But the Rolling Stones—five tough, young London-based music makers with door-stop mouths, palled cheeks and unkempt hair—are not worried what mums think.” Andrew cultivated their image as marauding sexual nomads. Mick and Keith might not have known it yet, but Brian did. Underneath the pissing outside, gum-under-the-desk hooligan antics was something much darker—rebel male youth preying on bourgeois girls.

Marianne was the perfect foil for Andrew’s young ruffians, her Continental refinement and angelic features throwing their vulgarity into high relief. The Stones, of course, were cast as corrupting pirates. But little did Andrew know, Marianne would be the one corrupting the Stones.

__________________________________

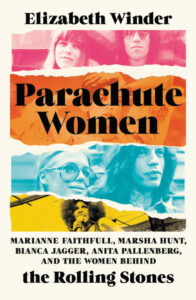

Excerpted from Parachute Women: Marianne Faithfull, Marsha Hunt, Bianca Jagger, Anita Pallenberg, and the Women Behind the Rolling Stones by Elizabeth Winder. Copyright © 2023. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Elizabeth Winder

Elizabeth Winder is the author of Marilyn in Manhattan: Her Year of Joy, and Pain, Parties, Work: Sylvia Plath in New York, Summer 1953. Her work has appeared in the Chicago Review, Antioch Review, American Letters, and other publications. She is a graduate of the College of William and Mary, and earned an MFA in creative writing from George Mason University.