Moments of Recognition: On Locating Queerness in Bureaucratic Records

Michael Waters Explores the Subjectivity of State Categorization of Queer Identities and Relationships

In 1932, Cary Grant and Randolph Scott began living together in an apartment in Los Angeles. Both were aspiring actors looking to save on rent. They found a house in Beverly Hills, and then, eventually, a beachside bungalow in Santa Monica. The two men had a tender relationship: together, they cooked meals like crab meat chow mein. One famous photo shows Scott gently touching Grant’s shoulders while both sit on the edge of a diving board. As the years passed, and as each man’s fame ballooned, rumors abounded about the exact nature of their relationship. Decades later, even historians have been split on exactly how romantic the pair were.

So you can only imagine what a challenge it must have been for the enumerator who showed up at their doorstep in 1940 to distill that relationship for the US Census. Ultimately, the Census enumerator decided to go with a descriptor that accounted for a variety of possibilities. That year’s Census listed Scott as the head of household and Grant as his “partner.”

Each moment of recognition was only possible because of the specific choices of an individual bureaucrat.

Over the centuries, enumerators for the US Census have captured all kinds of unofficial relationships between members of a household, as Dan Bouk outlined in his book Democracy’s Data: The Hidden Stories in the U.S. Census and How to Read Them. You can find 105 examples of people classified as “concubine/mistress and children,” for example. But “partners” became a popular way for bureaucrats to describe people who shared a household but who existed outside of the heterosexual nuclear family unit. Bouk identified over 200,000 examples of “partners” in Census ledgers.

Were “partners” necessarily queer? Not by any means. “Is it a dodge if I say that every partner shows us a queer couple, but only if we take a very broad definition of ‘queer,’” Bouk told me recently. “These are all folks who didn’t fit into the form. They were not in heterosexual households, not living with their spouses, not forming patriarchal nuclear families.” “Partners” included likely same-sex couples, yes, but also households of immigrant laundry workers. Still, according to Bouk, you do see higher rates of “partner” classifications in areas known for their gay populations, such as Greenwich Village.

Today, the “partners” category is one of many haphazard bureaucratic designations that let us trace queerness back through time. Especially in the early 20th century, before an organized anti-queer movement had crystallized, queer people were able to weave their way through bureaucratic systems that weren’t designed for them. You can see traces of queerness in the US Census, in name-change petitions, and even in marriage records. Paradoxically, the absence of legislation around how to classify queer people offered new paths toward visibility. You just had to know where to look.

Bureaucratic classifications of queerness have always been highly subjective. Take the history of trans and intersex people petitioning for name changes, for example. Up until the Cold War, no state had a law formally clarifying whether names could be amended after a gender transition, so local judges decided whether to approve these petitions at their whim. Often, a trans person would not be allowed to change their birth certificate. But sometimes, they were.

In 1941, Barbara Ann Richards told a Los Angeles judge that she wanted to amend her birth certificate because she had “metamorphosized” into a woman. “I began to observe that my skin had become smoother, that the shape of my face was different, my waist was smaller, my hips heavier, my throat smaller,” she informed the court. It was a fanciful story, but it was probably the only way Richards, who probably fits a contemporary definition of trans, could be taken seriously. In the end, the judge approved her name-change petition.

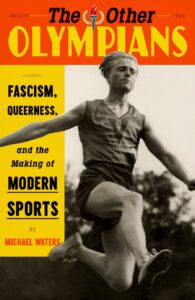

Cases like Richards’ are more common than we realize. According to one letter originally shared with me by the scholar Paisley Currah, New York officials reported in 1965 that they had uncovered “some twenty cases” of municipalities outside of New York amending birth certificates in response to requests by trans people. In my new book, The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports, I tracked the life of Mark Weston, a shotputter from Plymouth, England, who underwent surgeries in April and May of 1936 and began living as a man. After his transition, British authorities quickly changed Weston’s name and sex marker. Just a few months later, in July, Weston was able to legally marry a woman, his longtime friend Alberta Bray.

There is something very slippery about the way bureaucracies decide to give, and take away, these gestures of recognition to queer people.

What connects these stories is that each moment of recognition was only possible because of the specific choices of an individual bureaucrat. With no clear policy to guide them, each bureaucrat seemed to wrestle with queerness in their own way. This push-and-pull played out even on official forms. The US Census Bureau recently published an intriguing paper that tracked people who had likely transitioned back to 1936. The paper identified a common tactic that trans people used to make themselves known: Many checked both the “M” and “F” sex boxes on U.S. Census forms. These forms weren’t really designed to capture the nuances of their identity, of course, but they made it fit their wishes anyway.

Queerness has always interacted with bureaucracy in these surprising sorts of ways. In 1976, when two women, Yolanda Daniel and Jo Ann Martinez, marched into a courthouse in Merced County, California, and asked for a marriage license, local officials were at a loss for what to do. They couldn’t find a legal statute preventing same-sex marriage; California law technically defined marriage as between “two persons.” No one had considered the possibility that those two persons would not be one man and one woman. Dumbfounded, the county clerk issued them a marriage license. The two women were legally wed in the state of California for two weeks—until the county counsel returned from a poorly timed vacation, and decided to revoke the marriage license.

I have been writing about the queer past for close to a decade now, and I have always been fascinated by the relationship between queerness and bureaucracy. How do we make sense of the fact that Barbara Ann Richards was able to change her birth certificate in 1941, when today, a state like Tennessee still does not allow it? Or that a California lesbian couple was able to get a marriage license, however briefly, in 1976, when, thirty-two years later, California voters affirmed the decisions to ban same-sex marriage? There is something very slippery about the way bureaucracies decide to give, and take away, these gestures of recognition to queer people.

Sure, mapping out wonky bureaucratic categories like “partners” today lets us see that queer communities have always existed in some form. But more importantly, I think, it also underscores the subjectivity of the categories themselves. How to classify queer people has so often come down to the individual interpretation of an enumerator, a bureaucrat, or a judge. To paraphrase Currah from his groundbreaking book Sex Is As Sex Does: Governing Transgender Identity, these official definitions—of marriage, of sex markers, of partnership—mean little other than what a particular bureaucrat, in a particular moment of time, says they mean. Legal recognition for queer people has always been a tenuous prospect.

__________________________________

The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports by Michael Waters is available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Michael Waters

Michael Waters has written for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New York Times, WIRED, Slate, Vox, and elsewhere. He was the 2021-22 New York Public Library Martin Duberman Visiting Scholar in LGBTQ studies and lives in Brooklyn.