Modern Parents Could Learn a Lot From Hunter-Gatherer Families

Michaeleen Doucleff on Childcare Throughout Human History

All humans are descended from hunter-gatherers in Africa. From Thaa here in Tanzania to Maria in the Yucatán, from my grandfather in Virginia to my husband’s ancestors in Macedonia, all humans share that history. We all evolved, over a few million years, from a troop of peculiar humanlike apes in Africa, who survived by picking berries, digging for wild tubers, scavenging meat leftover from bigger predators, and—eventually—hunting and fishing.

No one knows for sure how our ancestors raised their children. We have no records of how a Paleolithic mom got kids to clean up after a meal, or how a Stone Age dad coaxed his toddler to sleep at night. We haven’t uncovered cave paintings of bedtime routines or petroglyphs offering tips for toddler tantrums.

But we can make educated guesses about some aspects of prehistoric parenting—about how our little humans adapted to be disciplined, motivated, and loved. And we can make those guesses by learning about the extraordinarily diverse cultures that exist on every habitable continent on earth. We can identify which parenting practices persist across the vast majority of these cultures—practices that have stood the test of time or cropped up over and over again throughout human history. And we can pay particular attention to cultures that still hunt and forage for part of their livings, since they hold a unique position in human history.

Our species, Homo sapiens, has been on earth for (very) roughly 200,000 years. And we spent the vast majority of that time, about 95 percent or so, as hunter-gatherers. First, we foraged in Africa (including the region where Rosy and I are scrambling to keep up with Thaa as he hunts); and eventually, we spread to every habitable continent on earth. About 12,000 years ago, some of us began to cultivate crops and raise livestock for our livelihoods. Then, less than two centuries ago, some of us ratcheted up the farming and ranching to such extraordinary levels that we now require gas-powered tractors, power saws, and robots to produce our daily calories.

So if we want to understand our species’ past, we essentially have two tools at hand: bones left in the ground by ancient people and the study of modern-day hunter-gatherer communities. The latter, as I have mentioned, are not “living fossils” or “relics from the past.” They do not show us how humans lived thousands of years ago. Instead, they offer a look at how humans can thrive as hunter-gatherers. On top of that, they’re living in a way that’s much closer to our species’ past than, say, my life in San Francisco, and they’ve held on to many ancient parenting traditions and techniques that Western culture has lost. Put simply, many hunter-gatherer communities have an enormous amount to teach Western moms and dads.

*

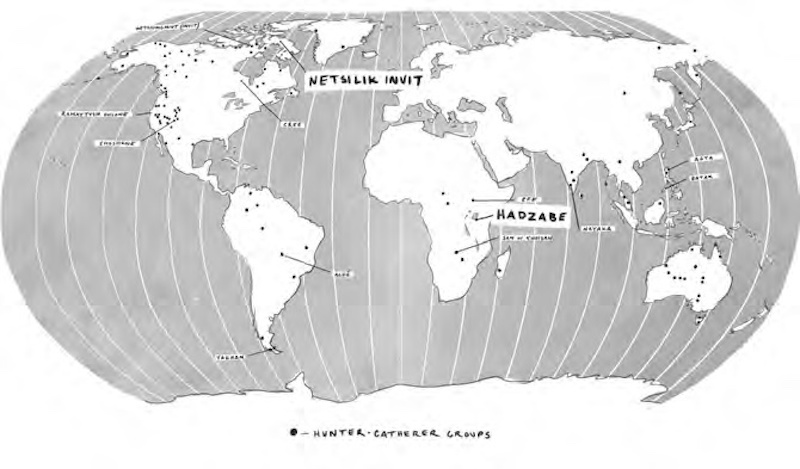

When journalists write about hunter-gatherers, like the Hadzabe, they often use words such as “rare” and “last.” But those adjectives give the wrong impression. First off, there are likely millions of hunter-gatherers currently living around the world. In 2000, anthropologists estimated that the population numbered around five million. These communities live across a huge swath of the Earth. They hunt monitor lizards across Western Australia. They track caribou across the Arctic tundra. And in India, where nearly a million hunter-gatherers live, they collect highly valued medicinal plants and wild honey.

In 1995, archaeologist Robert Kelly compiled a summary of Western knowledge of foraging societies worldwide. The resulting book, called The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers, describes scores of cultures worldwide, including more than a dozen in what we now call the United States. Not that long ago, hunter-gatherers managed large areas of North America, from the Shoshone and Kiowa people in the Rocky Mountains to the Cree in the Midwest.

In fact, right now, as I write these words, I sit on a peninsula that, some 200 years ago, belonged to a group of highly skilled hunter-gatherers called the Ramaytush Ohlone. They fished in the bay, foraged for acorns in oak forests, and collected mussels along the coast. These were the original people in San Francisco. Then Spanish missionaries arrived in the late 1700s, and almost every family died from disease or hunger.

Robert’s book aptly illustrates not only how “common” hunter-gatherer cultures are, but also how remarkably diverse they are now, were in the past, and will be in the future. Some hunter-gatherer groups rely largely on hunting or fishing; some on foraging. Some live in large, settled groups; others in small, nomadic camps. Many have moral systems based on equality for all people; others, not so much. Some cultures tend to have lots of babies with big families; some tend to be more like me and Matt—one or two and done. And essentially all hunter-gatherer cultures do more than hunt, gather, and fish for a living. “The reader should know that many of these ‘hunter-gatherers’ grow some of their own food, trade with agriculturalists for produce or participate in cash economies,” Robert writes. “Would the real hunter-gatherer please stand up!”

On top of that, none of these cultures are “undisturbed,” “pristine,” or “cut off” from the rest of the world. Every culture communicates and trades with other cultures, nearby and even far away. Every culture teaches and learns from other cultures. Every culture is interconnected and linked to others.

Many hunter-gatherer communities have an enormous amount to teach Western moms and dads.

The Hadzabe in northern Tanzania are no different. For thousands of years, the Hadzabe have lived in a vast savanna woodland, about the size of Rhode Island, surrounding a massive saltwater lake. Throughout that entire time, they have hunted wild animals, including large ones (giraffes, hippopotamuses, eland) and small ones (rabbits, wild cats, small antelope, squirrels, mice). They have snatched fresh meat away from feasting lions (“easy food”), collected honey from trees (the “gold in life”), dug for yam-shaped tubers, and snacked on the tart, crunchy fruit of baobab trees. They have lived in dome-shaped huts made of branches and grasses, which women can easily build in about two hours.

In other words, the Hadzabe have lived similar to the way their ancestors have lived for thousands of years, not because the people have been isolated or not exposed to other ways of living, but because the people believe their way of living is optimal for the harsh environment in which they live. And it’s true: Hadzabe have been quite successful for a long, long time. Why fix what’s not broken?

The Hadzabe have been so successful, in large part, because of their long-standing relationship with the land. Westerners would call it “sustainable.” Families work together with the plants and animals around them so that they all can coexist and thrive across millennia. It’s a relationship based on minimal interference and respect, instead of control and transformation, as Westerners tend to practice. The plant ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer calls this approach to life the “gift economy.” The land gives the Hadzabe families dik-diks, baboons, and tubers and in return for these gifts, the Hadzabe have a responsibility to the land—to take care of it and preserve it. The relationship is one of reciprocity. It’s bidirectional.

In her brilliant book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin writes:

“In the gift economy, gifts are not free. The essence of the gift is that it creates a set of relationships. The currency of a gift economy is, at its root, reciprocity In a gift economy property has a ‘bundle of responsibilities’ attached.”

Put another way, the giving flows in both directions, from land to people and back to the land. And so do the responsibilities. For every gift the land gives the people, the people are expected to give some of the gift back to the land.

During the short time I spend with the Hadzabe families, I can see the gift economy everywhere—in how they treat the animals they hunted, how they share every single plant they foraged, how they waste basically no food, and how they generate essentially no trash. I also see the gift economy in their relationship with their children. The parents don’t aim to transform the children into some ideal, as fast as possible, through control and domination. Rather, they focus on giving to each other. The parent continually gives the child gifts of love, companionship, and food, and in return, the parent expects a “bundle of responsibilities.” We coexist together, with minimal interference and mutual respect; and through reciprocity, we love and connect. In my clumsy Western way, I created a motto for this relationship style: You go about your business and I’ll go about mine, and we’ll always look for ways to help each other as much as possible.

This way of treating—and thinking about—children isn’t unique to the Hadzabe. You can find a similar style across many, many hunter-gatherer communities and other Indigenous cultures. And that commonality makes this parenting approach so extraordinary and so important: despite the vast diversity that exists among hunter-gatherer cultures, you can still trace a common way of raising and interacting with children—a way that has likely survived thousands, perhaps tens of thousands of years (or even more). This way, as we’ll learn, fits children’s needs—mentally and physically—like a hand fits a perfectly tailored glove. Or even better, like a Nejire kumi tsugi Japanese wood joint. It’s beautiful.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Hunt, Gather, Parent: What Ancient Cultures Can Teach Us About the Lost Art of Raising Happy, Helpful Little Humans, by Michaeleen Doucleff. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Michaeleen Doucleff.

Michaeleen Doucleff

Michaeleen Doucleff is a correspondent for NPR’s Science Desk. In 2015, she was part of the team that earned a George Foster Peabody award for its coverage of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Prior to joining NPR, Doucleff was an editor at the journal Cell, where she wrote about the science behind pop culture. She has a doctorate in chemistry from the University of California, Berkeley, and a master’s degree in viticulture and enology from the University of California, Davis. She lives with her husband, daughter, and German shepherd, Mango, in San Francisco.