Missed Chances for Mindfulness: On Trying and Failing to Meditate

Zach Zimmerman Searches for Inner Peace in a World of Constant Distractions

Some days I feel like an orb of divine, transcendent light that has severed the cord of desire, no longer experiences suffering, and floats above problems like a cherub on a cloud. Other days, I plot the murder of the guy doing construction in the apartment above mine.

An eight-week online meditation course first got me in touch with the former. It was free, one of my favorite four-letter words, and during the lockdown I had nothing to do. It was time to do nothing.

“Let’s all take a moment to close our eyes and become aware of our breathing,” the instructor began. He was a kind and gentle man, like meditators often are, with a bald head, as the enlightened often have.

“It might have been some time since we checked in with ourselves. So just take this moment to become aware.”

Despite the airy nature of his language, the class had been developed at a medical school. Jon Kabat-Zinn’s pitch was that if people with chronic pain could experience pain without judgment, they might suffer less. Contrary to many of my life choices, I am open to suffering less.

Eight other meditators on my screen—some young, some old, some hippies, some businesspeople—closed their eyes. My heart rate sped up. I closed my eyes and welcomed the thoughts of the enlightened:

This is a waste of time. What’s the point? My butt hurts.

Over the course of two hours, we did some short guided meditations and light yoga. It was hard, but when the class finally ended, I felt refreshed and renewed. I was even looking forward to the next session a week later until I learned there would be homework: an hour of meditation a day, every day.

I begrudgingly laid on the floor of my apartment the next morning and listened to a recorded guided meditation.

“What does your toe have for you today?”

Frankly, my toe wasn’t giving me a lot of data.

“Now focus on your other toes and up your left foot,” the recording continued. “And up your left leg.”

Contrary to many of my life choices, I am open to suffering less.There was a sensation on my leg at least, which made me wonder if something was wrong.

“Thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations come and go,” the recording seemed to respond. “We are simply observing them without judgment.”

But my butt like really hurts. Am I dying? Also, what if a tweet of mine is going viral right now? I should check my phone.

I finished the session, stretched my butt, and checked my device for the waterfall of texts and likes. Nothing.

Every day for the next six, I laid on the floor of my tiny apartment and trained my brain to focus on parts of my body where nothing was happening. At our next group session, everyone shared stories of how hard it was to make time for the assignment. I was unemployed, so time wasn’t the problem; it was just spending time alone with myself that scared me.

This is a waste of time. What’s the point? You’re worthless.

“During our fifth week, we’ll be doing a full day of silent meditation,” the instructor let us know. “In a way, this is all practice for that.”

*

After my first year of college, when I learned not everyone is an evangelical, including myself, I decided to find out as much as I could about “all the other crazy things people believe.” A web search of “summer Buddhism,” funding from my school’s Office of Religious Life, and flights from Virginia to Texas to Tokyo to Taiwan took me out of the country for the first time.

Venerable Yifa, a 5-foot-tall nun with a shaved head, greeted me at the Taipei airport. She was laughing like she knew something I didn’t.

“Welcome, Zach! You will enjoy your time here, OK?” she assured me as she guided me toward a white van. For the next thirty days, I would live like a Buddhist monk.

The monastery was a sort of college campus: dorms, a cafeteria, classrooms, gardens, pathways, and a village of meditation halls. Forty other students and I stayed four to a room and were given off-white robes to wear. Days were filled with lectures on classic Buddhist texts, and nights with silent meditation. Less was more here, so nothing was everything: no laptops, no cell phones, no meat, no self.

We used chopsticks—a novelty to me at home, a necessity here—to take our meals in silence in a large dining hall. Our last bit of bok choy was used to mop up any final pieces of rice in our soup bowl. Nothing was wasted. Our minds and our bellies were full.

In the presence of religious authority, I rebelled. When we took brooms to an abandoned part of the facility for “sweeping meditation,” I questioned the enlightenment value of the activity. The swarm of mosquitoes we disturbed agreed. Some participants decided to shave their heads as a sign of detachment from desire and freedom from vanity. I opted to keep my locks.

The trip culminated in a weeklong silent meditation retreat. We entered the dimly lit rectangular meditation hall that would be our home away from home for seven silent days. Our seats were around its perimeter, and our eyes were looking downward as even eye contact broke the silence.

Seated meditation is particularly challenging for the tall. I’m mostly leg, so folding my tree trunks up in nice, neat, sturdy ways is a struggle. Enlightenment might be the remit of those already a bit closer to the ground. During the first day I stretched them as far as I could, but the dull pain brought negative thoughts.

What’s the point of this? Why am I even here? This is a waste of time.

“Focus on your object of meditation,” Yifa instructed.

Frustrated and bored, I decided to sing through Legally Blonde: The Musical. One and a half Legally Blondes before walking meditation, another Act One before lunch. On the fourth hour of silence on the fourth day, during my ninety-second recitation of Elle Woods’s journey of self-actualization, my mood plummeted. I felt separated from my home, friends, and family, from verbal connections, jokes, and conversation. The silence hurt, like someone ignoring your screams. Frustrated, I opened my eyes and saw my peers: forty little unmovable mountains on their mats. I wasn’t alone at all.

The week ended in a pilgrimage to the top of a small mountain. We took two steps, then bowed on our knees, rose, two steps, bowed, two steps, bowed. When we reached the top of the summit, a large golden Buddha shrine looked down. I felt awe, not at anything divine, but at the human discipline that built this figure, standing tall 100 feet above us all.

*

When it was time for my one-day digital silent meditation retreat, the instructor covered his clock. The more I had meditated during the course, the more familiar I became with my particular stream of cruelty.

Time wasn’t the problem; it was just spending time alone with myself that scared me.This is a waste of time. Go do something. You’re worthless.

I’d listened to these talk tracks for decades, but for the first time, I could feel how they were affecting my body. It took a year of silence for me to hear how the noise of my mind, the stream of negative self-talk and judgment I didn’t question, was adding to my suffering.

This is a waste of time is the waste of time.

I placed a hand on my heart, a move the instructor had taught us, and gave myself some love. For lunch, I had some Starbucks brand string cheese. The next day I opened my phone and in the stream of close-up selfies, jokes, status updates, and news—real and fake—I saw a familiar nun in a brown robe. Yifa was livestreaming her meditation.

“The first day, I did the online meditation with no preparation,

OK?” Yifa told me after I messaged her to catch up. “The second day, the camera was sideways. Ninety degrees upside down!” She laughed.

“How many people watched?”

“The first night had six hundred viewers on the Facebook live-stream. The second: twenty viewers.”

She laughed again.

“If my purpose is to become a guru with one million people, that life is lousy. I would try to please these people.”

Always a good teacher, she turned the conversation toward her student.

“Don’t just follow the outside. Zach, if you don’t have your own inside life, you will get lost, OK? Our life has up and down, success and failure, perfection and imperfection. C’est la vie.”

“Is that a Buddhist teaching?” I joked.

“It is French.”

My joke had not landed.

“Buddhism mentions dukkha—life is suffering. Not painful, but unsatisfied. When you are not satisfied with your life, you are suffering.”

I complained to my landlord about the construction above my apartment, and he offered to lower my rent. With the extra funds I joined a coworking space that boasted a quiet room. On my first day, I took a seat in a cubicle by a few other workers. It felt sacred, silent, like the meditation hall in Taiwan, where little mountains worked on their own and together to not drown in the waterfall.

Just as I got to work, a jackhammer operator got to work outside. The machinery shattered the silence.

I paused, took a deep breath (in and out), and put in headphones.

Murder would just add to the noise.

__________________________________

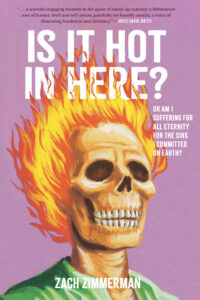

Excerpted from Is It Hot in Here? (Or Am I Suffering for All Eternity for the Sins I Committed on Earth)? by Zach Zimmerman. Copyright © 2023. Available from Chronicle Books.