Emer

On March 20, at 6:37 p.m., Emer Gunnels sat on the Lexington Avenue IRT line subway deep below Manhattan hurtling toward the future, hopefully making a stop at Ninety-sixth Street as well. She tried to avert her gaze from any man. She didn’t consider herself beautiful, but she had something some men sometimes liked. Some thing. Some times. Some men. Like she was in on the big joke. A blue-green refraction in her eyes of some charismatic, universal, lighthearted melancholy, like she saw things at a distance, a gently ironic remove. She dabbled in yoga; she could sometimes be found on a Stairmaster or a stationary bike; she was a New Yorker.

Here in the simulated captivity of a subway car, it seemed that the male imperative to gaze unapologetically at the female was a creepy game of chicken. The manspreading, lip licking, eye fucking—exhausting. These were men who would never act this way up in the disinfecting light of the street, but down in the subway, confined, these same males reverted to a kind of primal, almost prison-like dominance-testing behavior. It’s like a big–game reserve underground, she thought. Every day down here was like a new Stanford experiment. Thanks be to Jobs for the iPhone, which seduced a good number of the underworld travelers into a zombified and harmless solipsistic reverie, though it also seemed to embolden others by adding a propulsive soundtrack to their passive ogling. It was as if they thought, like children, if they couldn’t hear you, then you couldn’t see them.

She laughed lightly at that thought, making inadvertent eye contact with a pin-striped homunculus across from her, who, taking this as a sign that Emer was into him, manspread his open lap over not one, not two, but almost three seats. This antisocial act of opening wide your legs to cover multiple seats, presumably to air out your impressive package, was a true urban media obsession for a couple months back in 2014 that had spawned its own word and six-day culture war.

She felt a cold bead of sweat liberate itself from her right armpit and track down her ribs to a latitude even with her belly button. The Manafort-looking manspreader in the pin-striped suit—could be a Wall Streeter, possibly a top one or ten percenter—arched his eyebrows and tilted his pelvis ever so slightly, subtly enough to maintain the wiggle room of plausible public deniability. He ran his tongue across his lips. Gross. And clichéd. Double whammy. She involuntarily winced and made a gagging motion, as one might wave a cross in front of Dracula.

“Here in the simulated captivity of a subway car, it seemed that the male imperative to gaze unapologetically at the female was a creepy game of chicken.”

It was rare that she was without a book—she favored nineteenth-century novelists: George Eliot, Jane Austen, Charles Dickens— but this was one of those times she lacked printed matter. She found that looking down at her smartphone or tablet as the train was moving made her dizzy and nauseated, and while she realized that some vomit might clear valuable space in this crowded car, she chose to pass the time by reading the signs and advertisements that lined the tops of the walls all around her. Ever since she could read, Emer had felt the compulsion to read and even reread—cereal boxes, toothpaste tubes, subway ads. She was a reader. It defined her. She fixed her gaze well above the lap of the manspreader and made out what she could.

The first ad that caught her eye was for the ambulance-chaser law firm of Washington, Liebowitz, and Gonzalez, offering lottery-type rewards for heartbreaking diagnoses—$5.3 million for lead poisoning, $6.3 million for rubella, $11.3 million for mesothelioma, and so on. The repetition of the .3 was slightly suspect. How could all the crappy tragedies that might befall you be worth a fortune point three hundred thousand? Emer did the dread math in her head that she was convinced we all do when faced with these types of Faustian lawsuit scenarios. 11.3 million for mesothelioma . . . uh, no, nope, pass, but 6.3 mill for a little rubella? Maybe, maybe. Beats working. What was rubella anyway?

Next to Washington, Liebowitz, and Gonzalez was a placard from a series the MTA had instituted called Trains of Thought, in which quotations from great literature and philosophy were randomly posted to entertain the masses in the midst of mass transit.

One morning as Gregor Samsa was waking from an anxious dream, he discovered that in his bed, he had been changed into a monstrous, verminous bug. –FRANZ KAFKA

“The Metamorphosis” was one of her favorite stories. She’d read somewhere that Kafka couldn’t get through a reading of his own work without collapsing into fits of laughter. A deadpan humor born of incomprehensible horror. The literary equivalent of her favorite comedian/actor—Buster Keaton. Kafka was a dark fantasist whose unadorned prose read like newspaper accounts from hell on earth. She wondered at the wisdom of bringing the specter of the cockroach, which was really the official anti-mascot of New York City, into the minds of subway riders trapped below-ground, a place arguably more hospitable to vermin than people. She had seen roaches the size of New Jersey and rats you could throw a saddle on play on the tracks like they owned the place, like a postapocalyptic Disney movie.

She did not like to kill anything and had been an on-and-off, semi-strict, nondogmatic, occasional vegetarian since college when she’d read Diet for a New America, but she made an exception for cockroaches, flies, and mosquitoes. (And really good sushi.) Some insects deserved to die. She thought briefly of the Zika virus and its sad crop of pin-skulled, brain-damaged infants. She had no children. She was forty-one years old.

“She readjusted her gaze to the next placard, which, she was warmed to see, featured a new Miss Subways competition. Miss Subways? Really?”

She quickly glanced down to see what el manspreader was doing, and shit goddammit, she met his eyes, and, having failed to hide a jittery and guilty flinch, she flailed around for something else to read. As she cast her eyes nervously about the car, she was surprised at the violent and vindictive fantasies of revenge that visited her. Her inner judge never had rehabilitation in mind—Hammurabian, very eye for an eye, and leaning heavily toward poetic justice. Vengeance would be taken from the man’s offending organs. A ball for an eyeball. An image flashed into her mind unbidden—of the offender’s junk stretched across the third rail as a train barreled down. She felt bad for visualizing that. A tad harsh, perhaps. Maybe the draconian Giuliani had recommended something like that. She shook her head, remembering the days of that lispy, hissy, death’s head of a mayor.

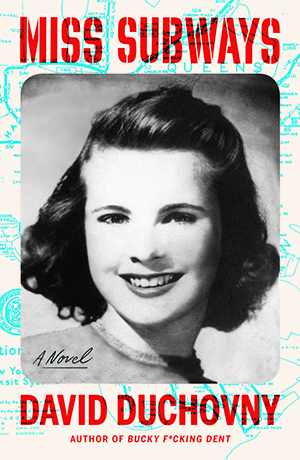

She readjusted her gaze to the next placard, which, she was warmed to see, featured a new Miss Subways competition. Miss Subways? Really? She happened to know all about that bygone “pageant.”

It was a real thing. She’d read about it in an Urban Studies program she’d taken a few years ago at Hunter College, where she’d decided to take a course every now and then, because, to paraphrase Dylan, if she wasn’t busy learning or being born, she was busy dying. The qualifications for entering the contest were both lax and touchingly parochial: she “had to be eligible, a NYC resident, and herself use the subway.” This was 1941, mind you. And yet as quaint as those strictures may seem, the contest itself was progressive, opening up to races and ethnicities that no other American pageant of the time would consider for decades. The clownish but deep former mayor Ed Koch had once said, “Even now, I can sit in the subway, and look up at the ads, and close my eyes, and there’s Miss Subways. She wasn’t the most beautiful girl in the world but she was ours.”

Thinking about a seemingly more innocent past, when the messiness of private life was no doubt the same, but the façade, how one spoke of the inside in public, was much simpler and the codes more easily figured, made her sleepy and warm. The lights flashed on and off like the staccato announcement of an epileptic seizure. “Dostoyevsky,” she muttered to herself, like an omen, another underground man. The subway itself was womb-like, dark, and humming—Emer, who could have trouble falling asleep in her bed at night, often dozed sitting straight up on her commute. Sleeping amid strangers on a crowded subway car in New York City—an act of trust to make any saint weep with joy. The train shuddered to an unscheduled stop between stations and the lights went out. Everyone groaned en masse. Perfect, Emer fretted, I’m already late. Con wants me there. He wants me there, but then he wants to ignore me. Like a child, a man-child. But that’s okay. This is his time, his time to shine, and she still had her secret wish, her secret plan within herself. A type of plan hatched in the infancy of civilization and the more primitive parts of a superstitious brain stem that lay underneath a rational modern forebrain, like water flowing under rock. A hope more than a plan, a wish she shared with no one for fear she’d be ridiculed as an old-fashioned gal.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Miss Subways by David Duchovny. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, May 1st 2018. Copyright © 2018 by David Duchovny. All rights reserved.