Misquoting Hippocrates to Promote Diet Culture?

How a Greek Figure Became the Face of Weight-Loss Campaigns

Diet books and plans come and go. Fats are in, carbs are out. Wellness is in, calorie counting is out. Fasting is in, keto is out. What remains consistent in these plans is their use of Hippocrates, the ancient Greek father of medicine, to promote dieting.

Among the books that used to be on my shelves, Hippocrates was quoted in The 17 Day Diet; The Adrenal Reset Diet: Strategically Cycle Carbs and Proteins to Lose Weight, Balance Hormones, and Move from Stressed to Thriving; Flat Food, Flat Stomach: The Law of Subtraction; Fat Loss Factor; and Eat Right 4 Your Type: The Individualized Diet Solution to Staying Healthy, Living Longer and Achieving Your Ideal Weight. Hippocrates also stars in Weight Watchers’ online calendar of Motivational Weight Loss Quotes. The Weight Watchers calendar is typical of the careless way in which Hippocrates is often used. The motivational quotation for May 8 is “Extreme remedies are very appropriate for extreme diseases” (Hippocrates), an incentive that is both vague and alarming and that appears to be contradicted by the motivational quotation for May 9: “Everything in excess is opposed by nature” (Hippocrates).

Hippocrates would not have endorsed modern diet culture: the restriction of calories in pursuit of a number on a scale and our obsession with being slim.

Most commonly Hippocrates is used to illustrate the simple idea that being fat is very unhealthy for you. For example, in the book Practical Paediatric Nutrition, we are told that obesity is “perhaps the most obvious situation which provides a health risk and which may be present, and preventable, in childhood. ‘Sudden death is more common in those who are naturally fat than in the lean’ (Hippocrates).” This is the most frequently quoted line from Hippocrates, and it is used to scaremonger: if you are fat you will die. It is a message that is consistent with our society’s prevailing attitudes toward fatness, that it is something to be feared. We are urged to “make war on” obesity as if fat bodies pose an equivalent threat to ISIS and to “tackle” obesity like one might a home invader. This, of course, makes a fat person feel at war with, and on guard against, her own self and encourages her, and others, to treat her body like an enemy of the state, which might not be the healthiest way to live either, but more of that later.

Hippocrates may seem like a surprising authority for modern health writers. Medicine has come a long way since the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. You don’t see modern doctors advocating his remedies in a hurry. His prescription for male pattern baldness was to apply to the head a mixture of opium, horseradish, pigeon shit, beetroot, and spices, and if that failed, castration was a possible surgical solution. Nor, thank goodness, are his cures for the “diseases of virgins” all the rage in today’s pediatric medicine, advocating as they do that girls should get married and have sex as soon as their menstrual periods start, to avoid going mad.

Diets, however, are often sold by appealing to the authority of the past: just as the paleo-diet craze seeks legitimation from the Paleolithic era, diets that quote Hippocrates seek legitimation from his legendary status as the first Western doctor. This itself is a bit of a fiction because Hippocrates cannot possibly have written all of the treatises that survive in the collection known as the Hippocratic Corpus. There are more than sixty of them, and they were written over a wide span of time—when we talk about “Hippocrates” we mean him or one of his associates.

Hippocrates would not have endorsed modern diet culture: the restriction of calories in pursuit of a number on a scale and our obsession with being slim. He did disapprove of gluttony: the excessive and extravagant consumption of food, drink, and other bodily pleasures, but gluttony was not typically associated with fatness in Hippocrates and other ancient writers. In ancient Greece, fat in general terms often had positive connotations of richness, prosperity, and thriving, while thin often suggested poverty and weakness. Some uncertainty is caused by the difficulties of translating from ancient Greek into English. The Greek adjective pachus, which is often translated as “fat,” can also mean “stout” and “stocky.” It could also suggest heft, both physically and socially, which our word fat does not. President Trump and former president Bill Clinton (before his weight loss) would likely have been called pachus.

In the Hippocratic Corpus, everyone’s body is considered constitutionally different and shaped by a variety of factors: geography, environment, bodily humors, diet, and exercise. Crucial for good health is getting these things in the right balance, but the Hippocratic writings never state that if you are fat it is important for your health that you lose weight. We are told that being fat could be detrimental to a woman’s fertility, but then so could living in cities that were exposed to hot winds. Hippocrates does give advice to people who are fat (or stocky) and who do want to lose weight: don’t eat while exercising, eat before you have cooled down after exercising, drink tepid, diluted wine before exercising, eat one meal a day, stop bathing, eat rich, seasoned food so that you will more easily be satisfied, and sleep on a hard bed. (I’m not sure about sleeping on a hard bed, but drinking wine before exercising makes me perk up when I contemplate a visit to 24 Hour Fitness.)

When it comes to the body, balance is key for Hippocrates. What of the diet books’ most frequently quoted line, “People who are naturally very fat are apt to die earlier than those who are thin”? This is one of Hippocrates’s aphorisms and is sandwiched between an observation that individuals who have been hanged by the neck and are unconscious but not quite dead will not recover if they are foaming at the mouth and the opinion that epilepsy in young people is most frequently alleviated by “changes of air, of country, and of ways of life.”

When it comes to the body, balance is key for Hippocrates.

There is no narrative context that expands upon and clarifies the saying. What’s more, even the meaning of that brief line isn’t quite clear. The Greek can mean that people who are naturally very fat will take less time to die, when they die, than people who are thin—not that they will die at a younger age or prematurely. We might think this is a good thing. The Aphorisms also contain other advice that is relevant to, but completely ignored by, modern diet gurus. Aphorism 1.5 advises against restrictive diets for healthy people (breaking such a diet was a risk to one’s health), and aphorism 2.16 warns: “When in a state of hunger, one ought not to work hard.’” Hippocrates’s outlook was considerably more complicated and varied than modern diet books that use him admit. When we select only quotations that may present fatness in a negative light, we distort the bigger picture in the Hippocratic Corpus and recruit Hippocrates as a spokesman against obesity, which he was not.

Why does it matter if diet peddlers misappropriate Hippocrates? I am not a purist or pedant when it comes to how we today understand and use antiquity. Misquoting ancient texts can be productive and creative. The distortion of Hippocrates bothers me because his writings are being conscripted by the diet industry to promote misery and sickness. I have been teaching in universities in England and in the United States for over twenty years. In my experience one of the biggest challenges to female students’ well-being, as great as exam stress and financial debts, is disordered eating.

When I had first started teaching at the University of Reading in England, one of my students, an intelligent, vibrant, lovely young woman, died from a heart attack brought on by chronic bulimia. Many other students with bulimia and anorexia have been unable to attend lectures regularly and their grades have suffered. Countless students (and colleagues) have confided that they are dissatisfied with their bodies. One of my female colleagues intermittently fasts, another rarely consumes anything when she’s at work except for a fermented milk drink, and another will not eat dairy, grains, gluten, or sugar.

Of course, men are affected by diet culture too. Even the Norse god Thor, in the movie Avengers: Endgame, cannot escape being shamed for having put on weight. However, he has not been reduced to marketing diet products as Wonder Woman has, with ThinkThin bars flashing from her bracelets; the message: dieting is empowerment. As Roxane Gay puts it, “the desire for weight loss is considered a default feature of womanhood”; in contrast, the desire for weight loss is not a default feature of manhood. The unhappiness caused by “normal” dieting and the mental real estate taken up by obsessing about food, is a staggering waste of our time, energy, and talent.

So why have I spent most of my life, since late childhood, on and off diets? It wasn’t for health reasons, even though I sometimes said it was, because I’m in pretty good health. Nor was it to feel more attractive (when I have been slim, I haven’t felt more attractive, but I have felt more accepted). I think it’s been for two reasons. The first is that thinness connotes success in our culture, while fatness suggests failure: moral and intellectual laziness and lack of self-control. Academic life is fiercely competitive: I wanted to be and look successful. The second is that, whereas the research part of my job can be done in private with no one watching me (the philosopher Jacques Derrida famously wrote in his pajamas), lecturing is a different matter. The spotlight is, quite literally, on me, along with the judging eyes of students. Undergraduates can be merciless in their scrutiny and their scorn.

The unhappiness caused by “normal” dieting and the mental real estate taken up by obsessing about food, is a staggering waste of our time, energy, and talent.

Academia, no less than the rest of society, is a world where stigma and shame around how you look is routine. The system of teaching evaluation questionnaires, the student feedback that plays a role in tenure and promotion evaluations, has recently come under attack for its gender and racial biases: studies have shown that students use different, and less positive, language for female professors and professors of color. Reading student questionnaires that comment on teachers’ looks can, for the fat professor, feel like being trolled. Appraising a professor’s appearance as well as their teaching was for many years encouraged and normalized by the popular website Rate My Professor, where students post public evaluations of their teachers, including, until 2018, “hotness” ratings: how many chili peppers did you get? Faculty also sit in judgment, though few are as overt in their contempt as the psychology professor at the University of New Mexico who, a few years ago, sent this tweet: “Dear obese PhD applicants: if you didn’t have the willpower to stop eating carbs, you won’t have the willpower to do a dissertation #truth.”

__________________________________

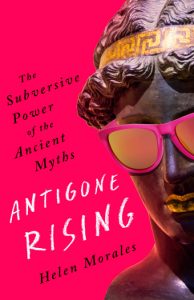

From Antigone Rising: The Subversive Power of the Ancient Myths by Helen Morales. Copyright © 2020. Available from Bold Type Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Helen Morales

Helen Morales holds the Argyropoulos Chair in Hellenic Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is the author of Classical Mythology: A Very Short Introduction and Pilgrimage to Dollywood: A Country Music Road Trip Through Tennessee, which inspired an honors history course about Dolly Parton at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. Morales has been a guest on BBC Radio 4 Women’s Hour, and her work has been cited in the New York Times and The New Yorker. Morales taught previously at the University of Cambridge, where she was a Fellow of Newnham College, and has been a Fellow at the Center for Hellenic Studies in DC. She is on the editorial board of Eidolon, the popular online journal dedicated to antiquity and feminism. She lives with her family in Santa Barbara.