Miriam Darlington on Why We Need the Wildness of the Great Gray Owl

“She had the most sensitive ears known to humankind. The owl didn’t miss a word.“

My son Benji saw the owl first. She was perched like a silky totem pole, talons grasping the gloved hand of her keeper. At first, too busy with getting a place in the queue for artisan bread, I walked straight past the owl man as he stood quietly holding his charge. How was it that they were barely visible? They blurred into the humdrum busyness of the townscape, as if there was something self-effacing—a kind of grayness, an owl-camouflage that both possessed. I learned then that the mind does not easily register things that we are not expecting to see.

The owl relies on the cryptic facets of its colors, markings, and posture to shield it from the gaze of others. But something about the plumage flared on the edge of my vision and perhaps my deep-seated fascination with owls made me turn, and when I saw her I lost all interest in buying fresh bread.

Benji was already right there. Together we stared. The Great Gray Owl, Strix nebulosa. Grail of the boreal forest.

Keenly aware, she gripped that leather glove tight as her head swiveled from side to side and her eyes settled on each and every distraction. I drifted closer, not wanting to startle her, but longing to be within reach of those smoky, brindled feathers. Could I touch?—Yes, it was important to get her used to people, he said. She was only a few months old.

Once we were conscious of being surrounded by wild things—they shaped who we were. Without their presence we feel, as poet John Burnside perfectly described, a sense of homesickness.

Her softness took my breath away. Deadly beauty. She turned her face towards me and I noticed its astounding circumference. There is a narrow area that falls between pleasing and preposterous, I thought, and this owl’s circular face and bright yellow eyes fitted into it with perfect grace. The massive facial disc, the owl man, Pete, explained to me, produces a funnel for sound that is the most effective in the animal kingdom; she had the most sensitive ears known to humankind. The owl didn’t miss a word.

Pete told us that he had known about the batch of three large, cream-colored eggs (which had been laid in this country by a captive owl) and once they hatched he had chosen this owlet at two weeks old and raised her. She had needed constant supervision and care, and was now, as with all young birds on seeing their first carer, “imprinted” upon him. They were inseparable. I watched as he repeatedly leant his cheek on her feathers, closed his eyes, and spoke to her with such tenderness that I felt as though I was intruding on a private conversation.

“I want an owl,” Benji said, his hand on my shoulder. “Can I have an owl?”

He must have known what I’d say. This is a wild creature. Shouldn’t it stay in the wild? We wrestled with ourselves, with our consciences, with our hearts.

When she was fully mature, Pete was planning to show his Great Gray Owl at the local rare-breeds sanctuary. My mind filled with a strange concoction of feelings. She’s a captive, I thought. A pet. She’ll be an exhibit, a misfit, unable to do what she has evolved to do, dependent on her enemies. She could be bred, Pete added, noticing my expression, and her chicks could be taken and released into the wild. Again he laid his face against her feathers and closed his eyes.

Could they be released? The laws around captive breeding are very strict on these matters, surely? The magnificent foreigner turned her head and looked past me with her lemon-colored eyes.

“The yellow eyes,” Pete said, “mean that she hunts in the daylight.”

Of course, in her native Lapland, during the summer months, there is no night-time. And in the winter, she must rely on her ears for the months of darkness. In spite of all the qualms, I was captivated.

Then, something startled her. For a split second she tottered on her tethers and I felt the breeze from her spreading wings. I must have closed my eyes, and when I opened them again, in front of me a striped gray haze of staggering silence and softness was rising; a giant butterfly, a god of the tundra. As her wings filled the air, I heard nothing but the whisper of snow falling in thickets of spruce and pine.

So what can a writer do, faced with a world whose wildness appears to be unravelling?

This owl’s origins were in the far north, in the boreal forest. To somebody out shopping for food at the market on a Saturday morning, from the cozy shires of England where at worst it is just wet in the winter, the very word “boreal” released an aromatic dream of resiny spruce forests, the whiff of wildcat, the pocked tracks of wolverine ghosting through the snowy tundra.

But this owl was on a leash. She bated again, tethered by jesses. Her wings worked, but she would never fly free. She righted herself, folded her wings, and settled, neatly doing what she was trained to do.

The joy of an encounter like this is always woven with an uncomfortable undercurrent. Owls, like so many species, no longer exist purely as astonishing, innocent, wild beings. They are emissaries from an imperilled ecosystem, rare representatives of natural freedom and abundance. Once we were conscious of being surrounded by wild things—they shaped who we were. Without their presence we feel, as poet John Burnside perfectly described, a sense of homesickness. Surely, to be fully human, we still need their wild company, even at a distance?

So what can a writer do, faced with a world whose wildness appears to be unravelling? The first thing perhaps is to get to know the wild, experience it, and pay attention to it. By giving our attention in this way we might avoid the blandification that happens, especially to so many “cute”-faced animals. As we “cutify” the natural world it is at risk of becoming tame and ornamental. Once we have encountered the wild face to face, been brushed by the downdraft of its phantom swoop or been awoken by that spine-shivering nocturnal cry, it becomes real, embedded in our minds, a subtle but vital part of our being.

Perhaps with this kind of attention, we can come to fully care: a word that derives from the Old English cearu, which means “to guard or watch,” “to trouble oneself.” Facing up to our scars and losses, taking the trouble and the time to explore the ecological details of some of the most fragile species and to record them accurately on the page, is the least we can do.

___________________________

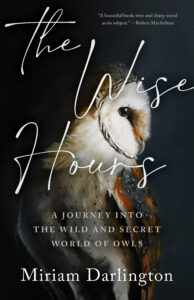

Excerpted from The Wise Hours: A Journey Into the Wild and Secret World of Owls by Miriam Darlington. Published with permission from Tin House. Copyright(c) 2018 by Miriam Darlington. First US Publication by Tin House, 2023.

Miriam Darlington

Miriam Darlington contributes frequently to The Times, The Guardian, and The Ecologist, and is also the author of Otter Country, forthcoming in the US from Tin House in 2024. She lives in Devon, England.