The car cuts through the landscape at high speed. The road is nearly perfectly straight, but even so, I keep glancing at the Israeli map unfurled across the seat next to me, fearing that I may get lost in the folds of a scene which fills me with a great feeling of alienation, seeing all the changes that have befallen it. It’s been a long time since I’ve passed through here, and wherever I look, all the changes constantly reassert the absence of anything Palestinian: the names of cities and villages on road signs, billboards written in Hebrew, new buildings, even vast fields abutting the horizon on my left and right. After a disappearance, that’s when the fly returns to hover over the painting. Little details drift along the length of the road, furtively hinting at a presence. Clothes hung out to dry behind a gas station, the driver of a slow vehicle I overtake, a thorn acacia tree standing alone in the fields, an old mastic tree. A few shepherds with their livestock on a distant hill. I look back at the Israeli map for a moment, to check that I should take the Kibbutz Galuyot exit to the right, and a moment later it’s announced by several giant signs, just as new high-rise buildings emerge from the horizon. From there, I’ll turn left onto Salama Road, where I’ll continue toward Yafa, or “Yafo,” as the signs directing me there declare, until the horizon materializes as a blue line. The sea! There it is, in real life, after years of absence, years in which it was nothing more than pale blue on a map. And now the sea, not the signs, begins to lead me toward the city, and as I drive on this bleak road, passing factories and auto repair shops, I cannot resist glancing at its trembling blueness every few seconds, until I almost cause an accident. During a brief glance at its rippling surface under the midday sun, I realize suddenly, but too late, that I’m driving through a red light, into a four-way intersection where each road has three lanes, and that all the cars are jolting to a stop to let me go through. Damn! What did I just do! After I pass through the intersection, I pull over on the side of the road to catch my breath, and a numbness extends into every part of me, making me feel heavy. I’m so clumsy; this is exactly the kind of border I cannot trespass. I can’t seem to calm down. But I can’t stay here either; my car is still obstructing traffic. I turn back onto the road, and my hands are trembling, they feel weightless now, while my feet barely manage to press the accelerator, the clutch, or the brake, and I make it to the end of the road, turn left, continue for a few meters, not much more, and arrive at my first destination, the Israel Defense Forces History Museum. When I arrive, I find that the parking lot is almost empty, which eases my anxiety, but also makes the task of deciding where to park the car a somewhat difficult endeavor. I’m not sure whether it’s better to park in the shade, or as close to the entrance as possible, or in a visible spot to prevent the car from being broken into or stolen, or somewhere no one else wants to park, where it’s less likely to be scratched, even a bit. When I finally park, after a not-so-insubstantial moment of hesitation, I put all the maps in my bag, as well as the shirt I’d taken off in the heat, and the two packs of chewing gum from the seat beside me, but not before opening one, taking two pieces of chewing gum, and tossing them into my mouth. Aside from coffee, I haven’t had anything to eat or drink since this morning, so at the very least I’ll absorb some sugar.

I get out of the car and walk calmly toward the museum entrance, then I cross the threshold into the lobby, heading straight for the ticket desk, when I discover a soldier standing there. He looks up at me with a smile. I walk over to him. He doesn’t ask to see my nice colleague’s identity card, so I leave it in my bag. I hand him the money for a ticket. And he takes it, gives me the ticket, and tells me I must leave my bag in a locker. That’s all. His military uniform must be part of the exhibition. I remove my wallet, and a little notebook and pen so that I can take notes, since photography is prohibited inside, as he also informs me. But I don’t have a camera with me anyway. I walk out of the lobby and into an open-air courtyard, which visitors must pass through to enter the sixteen exhibition rooms, as indicated in the brochure which the soldier gave me along with my ticket. When I step into the courtyard, I’m instantly met by a sharp, blinding light reflected toward me by the white gravel covering the ground, which also makes a terrible ear-piercing sound as I walk across it. To be quite honest, I have no more tolerance for gravel than for dust. So I keep walking across the gravel, carefully, trying to keep the sound from growing, and through eyes half-closed against the glare I see silhouettes of several old military vehicles positioned around the courtyard, until eventually I realize that this is the sixteenth and final stop in the exhibition, according to the brochure, meant to be visited after all the rooms inside. I feel a wave of nervousness when I realize that I’ve wandered in the opposite direction to the route suggested by the museum, which might ruin the whole experience for me, so I immediately head to the first exhibition room. And as soon as my feet cross the threshold, leaving the sticky heat that weighed heavily on the courtyard behind me, shivers rise through my body, in response to the cold air being expelled toward me by the air conditioning. I use my hands, which are still holding my wallet and notebook, to cover my arms, trying to warm them up, since I left my long-sleeve shirt with my bag in the locker. But it’s in vain. Shivers grip my body again as I wander through the room, which is completely empty of people, aside from a soldier on guard. I try hard to control my shivering, so as not to attract his attention while wandering leisurely in the room among the displays. In one, I find a map of the south and several telegrams sent between soldiers stationed there in the late forties, filled with heroic and encouraging phrases. But the shivering doesn’t stop. I take a deep breath, then turn to look at the guard, who I find staring in my direction. I turn away nonchalantly and keep walking, on toward the second room. There, my shivering gradually fades when I stop in front of a collection of photographs and propaganda films, a few of which, the labels indicate, were produced in the thirties and forties by pioneers of Zionist cinema. The films show Jewish European immigrants in Palestine, focusing on scenes of them engaged in agricultural work, and of cooperative life in the settlements. One film in particular gives me pause. It starts with a shot of a barren expanse, then abruptly a group of settlers in shorts and short-sleeve shirts enter the frame. They start constructing a tall tower and wooden huts, working until these are complete, and the film ends with the settlers gathered in front of the finished buildings, with joined hands, dancing in a circle. In order to watch it again, I rewind it to the beginning. The settlers break the circle, then go back to the huts they’ve just finished building, dismantle them, carry the pieces off in carts, and exit the frame. I fast-forward the tape. Then I rewind it. Again and again, I build settlements and dismantle them, until I realize that I shouldn’t waste any more time here; I have to visit several other rooms and inspect their displays, and there is still a long trip ahead. I continue my tour until I reach the sixth room, where I end up spending more time than in the previous rooms. This display features wax soldiers wearing various kinds of military attire and accessories. According to the labels, most of the items were used during the forties. I notice that military uniforms from that period differ from military uniforms today. Contemporary ones are a dark olive-green, while the old ones were gray and came in two styles, long pants or shorts, each held up by a wide fabric webbing with a leather gun holster, small pouches for magazines, and a place to hang a water bottle. There are different kinds of webbing sets, too, some worn around the waist, others across the chest. The wax soldiers also wear kit bags on their backs and have caps on their heads, some large and others small. As for their boots, these very much resemble the ones worn by soldiers today. In the middle of the room are huge glass cases, inside which are displayed various types of equipment and mess kits used at the time, including small rectangular tin bowls connected to a chain with a spoon, fork, and knife. There are other types of equipment too, such as shaving kits and bars of soap and so on. Next to all this is a little scale model of the tents used for soldiers’ quarters, mess halls, and command meetings. I continue to the next rooms, which contain displays that don’t deserve much attention, that is, until I reach the thirteenth room. The thirteenth room contains various models of small firearms that were used until the fifties. I circle them apprehensively, contemplating the different sizes and shapes, and the size of the bullets displayed alongside the guns in the glass cases, reading the accompanying explanations attentively, before pausing in front of a Tommy gun. The label explains that this is an example of a US-made submachine gun, developed in 1918 by John T. Thompson, thus the name “Tommy,” and widely used during the Second World War by the Allied Powers, especially by noncommissioned officers and patrol commanders, and then in the War of 1948, and subsequently in the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and many others. This weapon excelled, the label adds, at hitting a target even at great distance, while also being effective in close combat. I make a sketch of it in my notebook. I’ve become bad at drawing. In the old days I used to be able to draw and reproduce shapes very precisely. Now, however, my lines are sharp, agitated, and unsteady, which distorts the weapon I’ve sketched so that it no longer really resembles the weapon used in the crime on the morning of August 13, 1949. Suddenly, a loud roar rises through the room, and I jump and start shivering again. I leave room thirteen and step into the courtyard before the air conditioner’s chill extends over the entire room. In the courtyard, I stumble upon the military vehicles used during that period, which I’d seen when I first entered, and am met by a thick wave of heat and blinding white light for a second time. Against this, the dark green shirt of the soldier on guard, whom I saw in the first room and who is now also wandering around the courtyard, soothes my eyes. But not my mental state. At the first sign of fear, I leave the courtyard, head to the lobby, retrieve my bag from the locker and walk to my little white car, which is still alone in the parking lot. Actually, there’s no need for me to spend any more time in this city. Official museums like this really have no valuable information to offer me, not even small details that could help me retell the girl’s story. I open my little notebook to study my distorted sketch of the Tommy gun, which looks more like a rotten piece of wood than a lethal weapon. I put the notebook in my bag, then pick up the Israeli map to determine my route to my next destination. I must get on Highway 4, which leads south, then, after Askalan and before Gaza, I’ll turn left onto Road 34, then right at Sderot onto Road 232, and I’ll continue on that until I reach my next destination. I toss the map onto the seat next to me, take the chewing gum from my mouth, drop it in the car ashtray, and depart.

There are other maps lying under the one I’ve tossed there, including ones that show Palestine as it was until 1948, but I don’t open them this time. I’m acquainted with enough people who are originally from this area to have a sense of how many villages and cities there used to be between Yafa and Askalan, before they were wiped from the earth’s face not long ago. Meanwhile, names of cities and settlements appear along the road, as do shapes of houses, fields, plants, streets, large signs, and people’s faces; all of this accompanies me on my journey while rejecting me too, provoking an inexplicable feeling of anxiety, until I catch sight of a checkpoint where police are inspecting the identity cards of passengers on a white bus just outside Rahat. There they are! And there is a policeman standing on the side of the road as well, ready to select a vehicle, stop it, and subject it to inspection. My heart beats faster at the base of my throat. I must turn my gaze away. I quickly glance at my bag, then plunge my right hand inside, searching for the packs of chewing gum, and when I find one I take out a piece, toss it into my mouth and begin chewing it, while letting my gaze hang on the ridgeline of the hills scattered on the left side of the road. I have to calm down. Although the car had been moving at ninety kilometers an hour, the closer it gets to the checkpoint, the more it slows down, nearly to a complete stop at the checkpoint itself; I swallow some saliva, still chewing the gum, and just as the car crosses the checkpoint it leaps back up to speed. I take a deep breath when the scene appears in the rearview mirror: the policemen busy examining the identity cards of passengers on the white bus, and another policeman standing nearby, considering the cars passing in front of him, still about to select one and stop it for inspection.

I continue sitting behind the wheel until exhaustion pounces on me again, and I lean my head back. There’s much less traffic now, and I have come far enough south that the sandy white hills dotted with small stones have been replaced by hills of yellow sand that look soft to the touch. Scraggy, pale green plants grow on some of the hills, reminiscent of the wilting rotten lettuce the amateur vegetable vendor tried to sell me for three times the price of normal lettuce in Ramallah’s closed vegetable market. I decide to stop the car by some fields to rest for a bit. I take the chewing gum from my mouth and deposit it in the ashtray, then close my eyes, hoping to nap in my seat for a few minutes. But I can’t manage to fall asleep; I feel as if anxiety is lashing at me, keeping me awake. Eventually, when I’ve lost all hope of resting, I pick up the maps from the seat next to me. First, I open the Israeli one and try to determine my position, relying on the number that appeared on the last sign I saw along the road. It seems I simply have to drive on a straight course, albeit a short one, and I’ll soon reach my next destination, which appears on the map as a small black dot, practically the only one in a vast sea of yellow. Next, I pick up the map showing the country until 1948, but I snap it shut as horror rushes over me. Palestinian villages, which on the Israeli map appear to have been swallowed by a yellow sea, appear on this one by the dozen, their names practically leaping off the page. I start the engine back up and set off toward my target.

I see it from afar, in the heart of the yellow hills, and the narrow asphalt road stretches between me and my destination, where a row of flowers and slender dwarf palm trees leads toward several red brick houses. Nirim settlement. When I reach the barrier gate at the main entrance, I stop the car and remain inside, waiting for someone to come out and inspect me, but nothing of the sort happens. After a while, I drive closer to the metal gate and security booth, but I don’t see anyone inside, so I get out of the car and head to the gate. The sun is very strong. I hold onto the bars of the gate, which are hot from the sun, then pull them back and open it myself. I get back in the car, drive through the gate, then get out, close it behind me, get back in the car, and drive slowly through the settlement. Before very long I arrive at what appears to be the old section; the place looks completely abandoned. To my right is a huge stable, and next to it a water tank on top of an old wooden tower, and to my left is a street, past which are several huts which look very similar to ones I saw in the film at the military museum in Yafa. This must be where the crime occurred. Maybe this hut is the one the platoon commander used as his quarters, and that older-looking one is where the girl was held and then raped by the rest of the soldiers. I get out of the car and approach the two huts. I stand in front of them for some time, contemplating them, then walk around them. After a while, I head toward a large storage building. But when I get closer, I realize that it’s locked. Again I circle the huts, then the storage depot across the street, and suddenly fear descends on me. Or maybe it’s been inside me this entire time and simply strikes whenever it wants, like now, for instance, so I hurry back to the car and try to calm myself. I have to calm down. I start the engine and drive back toward the settlement entrance. But instead of going through it, I turn left onto a side street a few meters before the entrance. I can’t leave so easily, not after everything I’ve endured to get here. I keep driving, without heading anywhere in particular. On the left side of the street there are big new houses, expanses of pale green grass unfurling in front of them, while on the right there is a barbed-wire fence, and behind it sandy hills that rise silently to the sky. I keep driving around the settlement, which seems empty of any life, past closed door after closed door, until finally, behind an insect screen, I see a half-opened glass door. I stop the car in the middle of the street and jump out, shouting hello in English. But no one responds so I shout again, louder this time: Hello. After a moment, a young man who looks about eighteen years old peers out. I ask where the settlement’s archives or museum are. He directs me to the main entrance and describes a little white building; that’s where the museum and archive are, he tells me. I return to the car, where a feeling of fear submerges me again. But despite it, I keep driving until I reach the settlement’s entrance. I pull over on the side of the road, stop the car, get out, and slam the door behind me, letting the sound merge with the birdsong that fills the air. I approach a little old white building which looks like the one the young man described. I knock on the door and wait in front of it for a while. No one answers. I call out hello in English, then call out again, louder. After a long pause, a reply comes from behind me. I turn toward the sound and find a man in his early seventies standing in front of me. I say hello for the third time, then ask if he knows whether there is anyone inside. He says the archive is closed, then asks what I want exactly. I tell him, stammering slightly, that I wanted to learn about the history of Nirim, and take a close look at a few documents, for some research I’m doing about the area, and that I’ve come a very long way specifically for this purpose. After a brief moment of silence, he replies that he is the person in charge of the museum and the archive, and that he’ll open them just for me, even though officially they close at one p.m. I thank him enthusiastically, and as soon as he opens the door, my heart beats so loudly that it might scare off the birds. We go inside, sweat dripping from our faces. He introduces himself, gestures for me to sit at a big table in the middle of a nearly empty room, then approaches a white cabinet on the wall to the right of the front door. Quite hot, isn’t it? he asks, opening little drawers in the cabinet, and taking out a few envelopes. Yes, unbearable, I reply, and he adds that he actually doesn’t mind the heat. It reminds him of the weather in Australia, to a certain extent. He emigrated from Australia in the fifties, and has lived in Nirim since he arrived. And my name? I reply with the first non-Arab name that comes to mind. And my research? It’s a study of the geography and social topography of the area, during the period between the late forties and early fifties. He returns to the table where I’m sitting, carrying several envelopes he’s taken from the drawers, sits down near me, and begins removing dozens of photographs and spreading them over the table’s extremely white surface. As he does, he explains that he’s not a specialized researcher like I am. He’s just fond of photography and history is all, that’s why he founded this simple museum, in an attempt to preserve Nirim’s history and archives. I ask him to tell me about the settlement’s history as I start flipping through the photographs. And he begins speaking in a voice so calm and clear, so untouched by stuttering, stammering, or rambling, that it feels as if he is smoothly unraveling a delicate thread, one which cannot easily be cut. “Nirim’s cornerstone was laid on the night of Yom Kippur in 1946. It was one of the eleven settlements established by members of Hashomer Hatzair and young Europeans who had arrived in the country at the end of the Second World War. They began constructing settlements in the Negev. At the time, the aim of their operation was to expand the territory of Jewish settlements in the south.

__________________________________

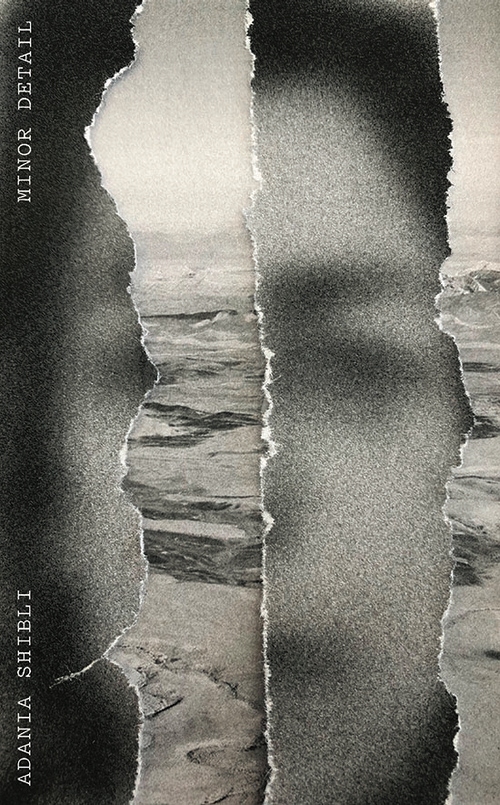

Excerpted from Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, New Directions Publishing.