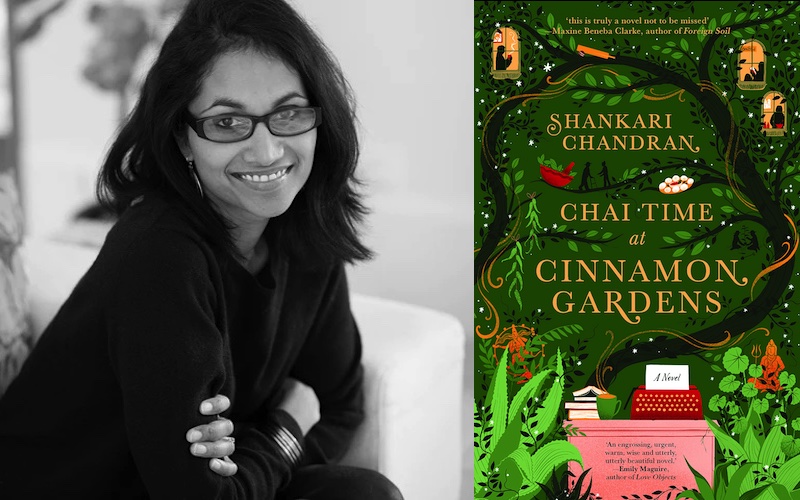

Miles Franklin Winner Shankari Chandran on Defining Australianness

In Conversation with Janet Manley

When she was querying her first manuscript, Shankari Chandran was told it was not Australian enough. Her third (published) book, Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens, came out in 2022, was set in contemporary Australia and 1980s Sri Lanka, and won this year’s Miles Franklin Literary Award, the top Australian gong—natch.

Cinnamon Gardens is centered on a Tamil-run nursing home in Western Sydney—a loaded geographical term, the city “center” being the Eastern suburbs, and the west where waves of immigrant communities have built their lives. Nursing homes are so often places of dispossession, where sense of self and history and even belongings disappear, but Cinnamon Gardens in the novel is a place that houses complex personal histories. It is run by Maya, who emigrated to Australia during the Sri Lankan Civil War. Maya is also a bestselling Australian author in the novel, but uses a nom de plume to appeal to a wider audience in a sharp piece of commentary on marketability. Her daughter Anjali helps run the home and watches the culture war play out among the youngest generation who, at one point in the novel, divide themselves on the school handball courts into dark and light-skinned. It’s a very ripe book for looking at Australianness, in other words, and how we talk about identity—national, cultural, ethnic, and on. It’s also quite witty amid the high stakes—when will people learn “chai tea” is tautological, one of the characters jokes.

Chandran was born in the UK to Sri Lankan Tamil parents, grew up in Australia and worked as a human rights attorney in London before returning to Australia to raise her family of four children. She hopped on Zoom to get into what Australian literature is (a conversation relevant also to the Pulitzer in the U.S. right now), how layers of identity work within a book, and what comes post post-colonial. This interview has been edited and condensed.

*

Literary Hub: There is a character, Maya, in the book who chooses to use a pen name to publish her work, and there are minor at least parallels with you trying to sell this manuscript and of course the history of women taking on male pen names and on. Could you talk about how you approached Maya and your experience in publishing?

Shankari Chandran: So my first novel Song of the Sun God was rejected when I put the manuscript out. I got an agent and she sent it out to the Australian publishing market, and the feedback was that it was not Australian enough to be published in Australia and that it wouldn’t sell books. Australian readers wouldn’t buy it, it wouldn’t connect with them. It was sort of that language. And that was a real repudiation of my identity and my place in Australia.

And I was enraged by it, but also more than anything really grief-stricken by it. So then with my next novel, The Barrier, I essentially went back to it and did control-all find-all replace-all. And I changed the central character whose name was Zakiya Ali to Noah Williams. And I made him a white character, a white protagonist, white male protagonist—in fact a white American protagonist. And that novel was picked up very quickly by an Australian publisher.

And then I wrote another manuscript that was a political thriller in the tradition of John le Carré. And I say this not because I have tickets on myself, but because I have a total mind crush on John le Carré, may he rest in peace, and thought he was the master of thrillers and of political thrillers in particular where the stakes are global. And I’d written this novel set in Sri Lanka at the end of the civil war that really explored the role of the superpowers and foreign governments and their geopolitical agendas and the way that they play god with little countries and people’s lives. And that manuscript did not get picked up because my sales had not been great for my second manuscript.

And so I figured my literary career in Australia was over, that I’d never be published again, and that was really liberating for me. I felt like I could write my next novel completely honestly, without any reference to publishers, to a market and indeed to readers.

Could I pull off the great white novel or even just a commercially successful white novel?

I then sat down to write a novel set in a nursing home, which was something I had wanted to do for a number of years because my grandmother lived her last years of her life in this beautiful nursing home that is in fact run by members of my extended family. And a lot of Sri Lankan Tamils and migrants are residents in this nursing home. Every fortnight I would take my children, we would visit my grandmother and she would talk to us about the past and tell us stories of her childhood and her life and her migration. And in doing so would telling us the stories of Sri Lanka and our culture and our heritage and our religion and our cooking and our community.

When we were going for walks around the nursing home, she would show me different residents and we’d stop at their rooms and she’d say, this is so-and-so and she would remember them and their stories from their childhood, their shared childhood and their shared youth far more clearly than she might remember what they had done yesterday together. They played bingo yesterday together. She won’t remember that, but she’ll remember that 30 years ago that that auntie had not invited her to a wedding, or her curry was better than her curry. And I thought, gosh, this is an extraordinary place of storytelling and an extraordinary place of community and the transfer of intergenerational knowledge. Let me try to write something about that. And I thought about writing a quirky novel set in a nursing home in the tradition of Joanna Nell, whose writing sort of is in that milieu.

I really wanted to and was ready to write about race in Australia, and that is a very difficult thing if you are not white. And in fact, even if you are white in Australia, you need to tread very carefully because my observation of Australia is that we are very sensitive about race and even the mildest assertion that there is racism in Australia and that we give anybody else anything other than less than a “fair go” is met with great defensiveness. And then the defensiveness turns to anger quite quickly, and so I’ve never wanted to stick my head above the parapet.

My own publishing experience of being told that I was not Australian enough and that my work was not Australian enough and therefore that I am not Australian enough, found its way into Maya and her experience of publishing. And Maya did that thing that I have joked about with my writers of color friends, which is should we just assume a nom de plume and write a novel about white people for white people? Because technically my craft by now is good enough. So could I pull off the great white novel or even just a commercially successful white novel?

So Maya Gay and Sarah Burns, her alter ego, gave me a way to really play with that and to have some fun with that. And what’s been interesting for me is that readers in Australia and in particular the publishing industry have winced but gone, it’s funny. It’s true.

LH: When you were creating these characters, how did you look at some of these scenarios in the book where you set up this mechanism for us to evaluate these assumptions about who is Australian and how?

SC: So the book starts with the question of who is Australian? But for me, the bigger question is who actually gets to decide? Who gets to decide it to the inclusion of some and the exclusion of others? And why is it that it’s so, and this for me in a way, on a personal level, is the more important question. Why is it so hard for us to talk about that?

The writer’s answer is that I looked to two novels. One was Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire, which I think is just an exquisite exploration of radicalization and relationships, and the form of it is perfect. The way that she executes the form of that novel, not just the language, but the form, the structure is perfect—for five chapters, everybody has about 50 pages, and it moves the story forward and alludes to what’s going to happen next and gives you enough to keep you riveted, but doesn’t give you the answer.

And the other novel was Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarti, one of Australia’s most commercially successful authors. And there is something in the structure and her voice and the readability of it that I really admire.

I knew that Maya and Reuben would be the emotional anchor of the book and the axis around which all of the action would revolve. Reuben gives you the story of that displacement from the Sri Lankan Tamil perspective. And whilst much of that is also Maya’s story, hers is the question of what does that mean when you come to Australia and how do you create community?

Initially when I created Gareth, he was going to deliver and drive the worst of white Australian society, but also the worst of all of our bigotries. I did not want him to be a farcical villain. I wanted him to be a man or a human that we know. Everybody knows a Gareth, everybody stands on the side of a football pitch with Gareth. And Gareth makes casually racist jokes and we laugh. But also we are Gareth, right? I am racist. I’m capable of bigotry and racism. And the difference between me and Gareth, I hope, is that I am constantly trying to check it. I am trying to be aware of it, and I’m trying to move it from my unconsciousness into my consciousness so that I can remediate it and do better.

LH: I’m curious how you think about talking about cultural inheritance and these many pieces of identity that we pick up. The idea of white Australians being Australian is a very manufactured idea. There’s not the, Well, I’m two generations from Ireland, or whatever.

SC: Yes, and two generations from Ireland or seven generations from England. There isn’t that. And my issue with this thinking is that some people are more Australian than others. So even I fall into these conversational hacks. I’m happy to use the hack of “South Asian: because there are so many of us while simultaneously recognizing that my Bengali friends think that they’re better at poetry than me, and that my Punjabi friends cook potatoes better than we do, but that our dosa are crispier. So these are the ongoing kind of conversations that we would have within ourselves, which are largely humorous and enduring.

And at the same time, what I don’t particularly like, is if someone says to me, if they assume that I must be Indian, as opposed to asking, what is your ancestry? And then a worse assumption is to assume that I’m not Australian, as opposed to asking, what is your ancestry? I have a mixed accent and I obviously have a different color of skin to many people. I would still like to be assumed to be Australian. And the respectful question, the curious question, and I asked this question because I’m extremely curious about people, because I am Sri Lankan Tamil, I think we are particularly curious about people’s origins. And so I always want to know what is someone’s ancestry? You would’ve noticed that for every one question you’ve asked me, I’ve come back with questions of my own about you, just the way we are. We’re super nosy people.

Language is power and language reveals your value set. So the language that you use around those questions is really important. And so in terms of cultural inheritance, it’s an interesting thing that I used to feel burdened by. Am I Australian? Am I Sri Lankan Tamil? Am I Sri Lankan as opposed to Sri Lankan Tamil? Or am I Tamil or am I Australian Tamil? So they’re all actually very different permutations because also Tamil people don’t always recognize Sri Lanka anymore because that is a political state that has oppressed the Tamil people. And therefore I have many family members and friends who would not refer to themselves as Sri Lankan Tamil, but as Australian Tamil, including my husband—my husband would say that we are Australian Tamil.

LH: So you’ve kind of led me into something that I did want to ask, which was that the book very nicely references the kind of affectation of Australianness. And that ocka-ness is threaded in with Colombo Tamil, Singhalese, different dialects, it is a multilingual novel. I’m wondering how you thought about nationality as a construct in the conscious decision to go beyond this simplistic idea of Alf from Home and Away going “strewth!”

SC: Yeah. Oh my goodness, Alf. And the thing about Alf from Home and Away, and the “she’ll be right mate” sort of language is that it absolutely exists. It’s here, of course, and it’s warming. That completely puts you at ease in a way that Sri Lankan Tamil just does not have the language for, because we’re always slightly on edge, always struggling to get into medical school or imagining a civil war around the corner. So there is something incredibly beautiful and relationship building and connection building about that language and the values and the goodness and the integrity that it reflects. I have no quarrel with that whatsoever. I love it. I think what the novel is trying to say is that there is space for all of it, and that all of it in time, if not right now, today, is as Australian as the rest of it.

And I can’t help myself but be facetious when I hear these people maintain the affectation of a particular kind of strangeness whilst actually living a completely different reality. And so my point to them is, why not just embody or be honest about your reality and allow that to be normalized as the rest of us are trying to allow our kind of Australianness to also be normalized and by clinging to the other kind of Australian and only that kind of Australian, you make it harder for everybody, and it’s dishonest and it’s patronizing to all Australians regardless of color.

LH: I’ve been gone for so long that people are just disappointed with my accent and it’s very enlightening to feel like you have lost a signifier and kind of a qualifier for a certain type of identity. So how do you, as someone who is in now in a cross-national marriage with someone who identifies as British Tamil and who herself identifies as Tamil Australian and now has kids think about home, homesickness, and belonging?

SC: So much of my writing is about home, the creation of home, the losing of home, of home being taken away by force, migration from home, and then the creation of a new home. And for the older generation of my family, they still will refer to back home and they mean Sri Lanka. And for many of them that are the really older ones, they mean Ceylon because it’s just so embedded in their language, but also in their mindset. So they will talk about “back home we used to,” or “when is she going back home” or “she’s visiting back home.” And I always used to think about that language, when is it, how long does one need to be in a country before one starts to think of it as home?

My daughter for her HSC here did visual arts and chose to do portraits of four generations of women, and to superimpose the portrait on an old map of the place, that person referred to as home. So my grandmother—my daughter’s great-grandmother—referred to home as Ceylon. So my daughter Laura drew my grandmother’s portrait on a map of Ceylon. For my mother it was Sri Lanka, for my daughter, it was Sydney, and for me at the time, it was London.

I think that that came from a feeling of not fitting in Australia, moved to London and felt myself exhale for the first time around cultural acceptance. Because in London, British Tamil culture was really visible and it was valued and people respected our art forms. We were journalists and lawyers and politicians and news readers. George Alagiah has recently passed away. He was the anchor of the BBC for decades. I was like, oh my God, a hot Sri Lankan Tamil guy is fronting BBC, and he was a household respected and trusted name. It was the first time in my life in London where I thought I could be an artist and tell stories that would be valued because I had never seen my stories told in Australia.

LH: Yeah, isn’t that interesting? You had to leave to get that. Which brings us to the Miles Franklin Award: do you think it changes something?

SC: It reflects the change in Australian leadership and it will drive change in Australian leadership, and I’m honored to be a part of both of that. I think it’s absolutely extraordinary since I was a young person. I absolutely loved Miles Franklin’s book, My Brilliant Career. I looked at the writers that won the Miles Franklin I and have considered it to be the pinnacle of literary recognition in Australia for Australian writing, which is exactly what it is. I’ve looked at those writers and just thought how extraordinary to achieve that, to be part of that canon and to shape that canon with your stories.

I think it reflects the change that is happening in Australian literature, and that has been happening for many years now in terms of what the curators of culture and publishers are allowing through to be published. And that does not reflect a change in the Australian readership. I think the Australian readership is sophisticated and is wanting diverse stories and recognizes and respects them. I think the publishing industry has had to learn that these stories are worthy of being told that there is a market for them and that they make money, and that none of those things are mutually exclusive and can coexist simultaneously, not surprisingly. And that therefore they should publish our work.

LH: Which does bring us to Yellowface.

CS: Okay, so this is fascinating. Yellowface is number one in Australia at the moment, and Yellowface is extraordinarily funny, and it’s very uncomfortable to read. R.F. Kuang nails the psyche of the insecure, aspiring author so well, it’s like she’s inside all our heads, but then takes it further because the protagonist does something that most of us would never, ever do: She adopts a persona and she steals the manuscript of an Asian-American friend who dies. And then she allows herself to be considered ethnically ambiguous in a way. And then she continues to plagiarize the work and pass it off as her own.

It’s such an interesting story because that vehicle is her way in to then critique what it means to be a diverse writer, the publishing industry and its own fickleness and the entitlement of different kinds of writers and the way that we as writers feel forced to play the game in order to game a system that is set up against us. And so it’s fascinating. She takes a big swing, talk about taking a swing.

Janet Manley

Janet Manley is a contributing editor at Literary Hub, and a very serious mind indeed. Get her newsletter here.