Megan Mayhew Bergman: Girl Scout Heart, Henry Miller Mind

On Ugliness, Underdogs, and the value of hard work

Almost Famous Women is Megan Mayhew-Bergman’s second collection. The stories are fiction, but the characters at their centers are real people, plucked from the fine print in history books. That common factor ties the stories together but never feels like a gimmick. In tugging on history’s loose threads, Bergman simply gathered what she needed to weave colorful, intricately textured stories. It’s an accomplishment that may bring Bergman a greater share of the very commodity she questions here: fame.

Was the title of this collection always going to be Almost Famous Women?

Megan Mayhew Bergman: For a while it was The Imagined Lives of Almost Famous Women—but my editor, agent, and I had a long discussion about how “Imagined Lives” was redundant, if the book was clearly labeled as fiction. As someone who loves economical writing, I was immediately onboard with shortening the title. Always trust the reader!

Writing historical fiction must have an added level of difficulty, because you’ve not only got to create these characters and plot their stories, but also have to keep track of so many details from life in the past. Your stories are set in so many different times and places. How did you ensure accuracy of historical information—was it a ton of research?

MMB: I had been reading about these women for a decade, and was really living with them inside of my imagination for years. (Oh, writers and their crazy talk). The great part about writing this book, for me, is that I love research. I’m a nerd at heart. I lost many writing days to research—what type of lipstick was historically accurate? What did the Guerlain perfume bottle look like in the early 40s?

I did, however, give myself permission to play, or write, outside the lines. For many of these women, so little was recorded about their lives, that I had to use my skills as a fiction writer to fill in the gaps. I was also intensely interested in their psychological landscapes—mainly as it pertained to risk taking and living “authentic” lives. If I were to attempt to describe my psychological landscape from last week, it would be a work of fiction, so I gave myself permission to write bravely, freely, and with good intentions. And by good intentions, I mean trying to use art to raise the truth, and not romanticizing my subjects.

Honestly, I was tired of seeing women of this era portrayed as overly pretty or sheathed in glittering dresses at a cocktail party. While I didn’t want to craft cautionary tales, I did want to spin narratives that were fascinating in all their ugliness. I didn’t obsess about the likability of my female protagonists—I wanted to render them in a way that honored the hard decisions they made.

I’m curious about the roots of these stories, where you first encountered these women and what made you decide to create characters out of them. Let’s start with Allegra Byron. Where did you hear about her?

MMB: I came across Allegra in a biography about Lord Byron, but it was Dolly Wilde’s mention of Allegra that made her stick in my imagination. Dolly always felt a kinship with Allegra—both of them in the shadow of famous male relatives, and both relegated to a convent during their childhood. Dolly and Allegra were both spirited and intelligent, but damaged in some way by their time in the convents and the weight of family names.

And the Hilton Sisters?

MMB: I was reading a website about Roadside Americana, and learned about the Hilton Sisters, who were conjoined twins in show business who were basically exploited and then discarded outside of a grocery store in Charlotte, North Carolina. Knowing what I know about the South, I thought: what was it like to endure the indignity of being a spectacle, to live with two minds and one body? I often use empathy as a way into a story.

OK, one more—what about Joe Carstairs?

MMB: Kate Summerscale’s biography on Joe is a must read—The Queen of Whale Cay. Joe’s strong sense of self and drive for power fascinated me. While I couldn’t empathize directly with that, I could imagine what it might have been like to be sucked into her orbit. My story about Joe is told from the view of a girlfriend whom Joe plucked from the mermaid acts in southern Florida.

There’s so much fertile ground for storytelling in the negative space of history and literature. Have you always been drawn to the backstories that aren’t being told, the characters on the periphery?

MMB: I love an underdog. This comes from my father, I think, who grew up poor and who always pulls for chronically undervalued—the sports team on a losing streak, the alcoholic janitor at his old office. My heart and mind have been trained this way—honor the complexity of the human condition, and don’t write off people who aren’t standing in the limelight. The seeking of limelight, or fame, intrigues me—which has a little to do with the theme of my book, and the Ezra Pound quote I used to kick it off, a line from The White Stag: “‘Tis fame we’re a-hunting, bid the world’s hounds come to horn!” Fame is a messy, brutal business.

I became aware of some criticism of the book along the lines of, “These women don’t deserve to be famous.” This line of thinking presumes that I believe “famous” to be a positive state of being, worthy of sacrifice. I don’t, necessarily.

It was important to me to write Almost Famous Women and not Almost Famous White Women or Almost Famous Straight Women. It’s a diverse collection, primarily because I believe women of color and women with alternative sexual preferences took the greatest risks to live as they wished.

You’re becoming more of a “famous woman” yourself. How does the increased attention on you and your work feel these days?

MMB: I had the great fortune of coming from a line of people who knew hard work. The privilege of that lineage is that you grow up a little hungry.

Even though I’ve had some success as a writer, I still chase a feeling of satisfaction. I’ve had to make myself aware of my hungry feelings so I can keep them in check; it’s easy to constantly recalibrate what defines personal success. If you keep moving the mark, which as a dreamer I tend to do, you keep falling short. Or perhaps the optimist reframes this as—you keep trying.

Beryl Markham has the greatest antidote to the dreamer’s mode of being, and I’ve taken her words to heart: Never hope more than you work. When it comes to my career, I often find myself torn between two notions: “Don’t take yourself so seriously” and “Take yourself seriously.”

I don’t read maps well or remember calculus, but I am a hard worker. That I can say about myself. But when you try hard at something, you make yourself vulnerable, because you’re expressing your hopes through that work. When you dare to take yourself seriously, you take a risk.

I’m five feet tall, blonde, dimpled, and sometimes speak with a Southern accent. I have a Girl Scout heart and a Henry Miller mind. Many people in my small town think I write children’s books. Sometimes I let people make the mistake that I’m as “cute” on the inside as I am on the outside, but I recall a piece of advice I was given by another woman: “No one will ever take you as seriously as you take yourself.”

As a fellow dimpled blonde Southerner with a dark(ish) heart, I relate.

MMB: I love finding other dark-hearted blonde Southerners. It’s a funny tribe.

Sometimes, before an event in Brooklyn, I’ll give myself a pep talk: Don’t giggle. Stop hugging everyone. Use a little French.

Increased attention is a blessing. It validates the hard work, but it’s also a form of pressure. I find that if I can get the self-regard piece in place—e.g. I feel good about the work I’m making, how I treat myself and the people around me—I can let the regard of others land as it may.

That sounds much more zen than it feels. Oh well. I’m a writer. I’m allowed to tell lies.

Finally, what’s your favorite thing about shopping in a real-life bookstore?

MMB: I live in rural Vermont, so I get starry-eyed about retail opportunities, I can’t lie. Whenever I’m in the city, or in Raleigh where I used to live, I like to drink fancy coffee and browse book stores. I love that sense of wonder-driven shopping. My favorite wonder-driven bookstore experiences are in old, used bookshops or at Northshire Books in Manchester, Vermont. A sense of discovery is the best. Recently I came away from an old shop in New York City with the 1960s Marilyn Monroe Eros book—it’s full of her last studio portraits and Robert Burns poetry.

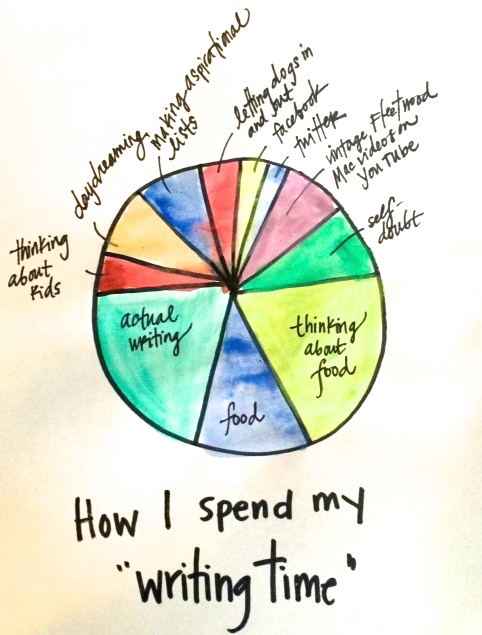

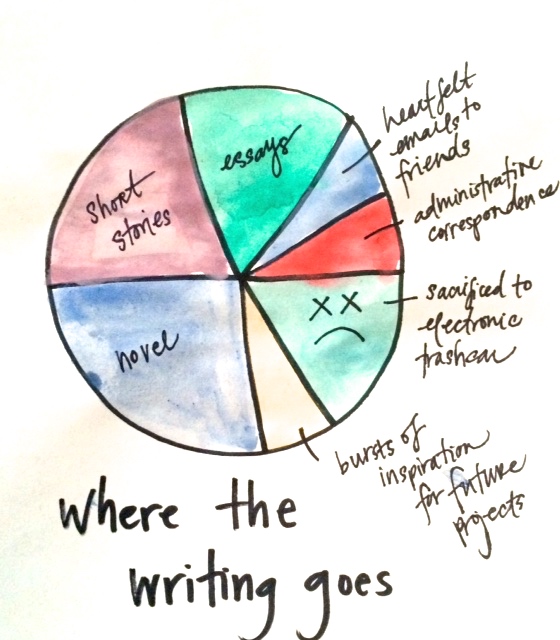

In response to a question about her writing—what gets used and what doesn’t, how time is used—Mayhew Bergman painted the following pie charts:

This interview also runs today on Musing, the online magazine of Nashville’s independent bookstore, Parnassus Books. Mary Laura Philpott is the editor of Musing, and the social media director at Parnassus.

Mary Laura Philpott

Mary Laura Philpott is the author of a forthcoming memoir-in-essays, I Miss You When I Blink (2019), as well as the illustrated humor collection, Penguins with People Problems. She also runs Musing, the online magazine of Parnassus Books, and co-hosts A Word on Words for Nashville Public Television. She’s on Twitter @marylauraph.