Megan Kamalei Kakimoto On The Many Ways To Tell a Hawaiian Story

"The only way to dismantle the perception of a monolithic Hawaiian experience is to uplift a multitude of Hawaiian stories"

The Night Marchers came before Aiko, the writer. In fact, the Night Marchers came well before my ancestors and will likely be around well after my own generation passes. I fear them as much as I revere them. For years, I could not write about them.

Known commonly as the spirits of ancient Hawaiian warriors, there are aspects of the Night Marchers most native Hawaiians will agree upon: they’re called huakaʻi pō or ʻoiʻo in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi; they frequent Hawaiʻi’s most sacred grounds; they are formidable protectors of sacred peoples who show no mercy in their craft. Equally, there exists a proliferation of guidance among people in Hawaiʻi on what to do if one finds themselves in the Night Marchers’ path:

Listen for the smell of lit torches and the thunderous ripple of the conch shell, a warning call.

Avoid sacred places especially on pō Kāne, the 27th night of the lunar moon.

If Night Marchers approach, strip naked and lie facedown.

DO NOT look them in the eyes.

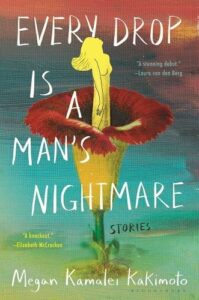

In Hawaiʻi, the legend of the Night Marchers is as ubiquitous as fresh poke or a trade wind breeze. You can’t spend any meaningful time in the islands without at least encountering their mention, and as a native Hawaiian, you certainly couldn’t pass through your childhood without abiding the warnings from your parents and your kūpuna to be wary of the Night Marchers. So when the collection that would become Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare announced itself to me, I knew instinctively it would not be complete without a story centering huakaʻi pō, the core of arguably Hawaiʻi’s most famous superstition. I also knew the risk lying dormant in this massive responsibility; that, though invisible to non-native Hawaiians, the story of the Night Marchers was a grenade I held in my hands.

What not-native readers could never understand: the weight of the inheritance that is ancient Hawaiian moʻolelo. The stories and narratives, the legends and myths that form the fabric of our cultural blanket. Like most Indigenous cultures, ours is one of oral storytelling, which affords a multiplicity of voices and versions of the same tale. The way I learned of the Night Marchers from my late grams is different from the way my parents talk about them, which in turn is different from how they were discussed in my school years at Kamehameha. Often when I was committing a blunder such as whistling at night, my parents would warn me: I was being foolish, calling forth the Night Marchers’ presence. The Night Marchers, then, were as much a fixture of ʻōiwi culture as they were the threat peering out from a cautionary tale. And while the variations of moʻolelo might offer for some writers a sense of permission granting, for me, a natural pessimist, the abundance of ways to tell this story petrified me.

Still, I had a nagging suspicion that no story collection centering the local superstitions of Hawaiʻi would feel complete without a tale of the Night Marchers. Even as I resisted committing them to paper, on several occasions I would pop my head out to draft a wobbly, watered-down interpretation of the classic tale and how the Night Marchers inserted themselves into the lives of mortals. Draft after draft, with every story falling short—too earnest, too ambiguous for the non-local reader, too flat, too forced.

Despite my awareness that the idea of a monolithic “Hawaiian” experience is nonsense, I was seeking nonetheless to create one on the page.Worse than flat and forced was the sense of wrongness that permeated every draft. The feeling that writing a superstition so deeply rooted in Hawaiian culture for what would be predominantly a white audience was a mistake, it was a story too sacred to touch. That the Night Marchers, like so many other tales inextricable from our heritage, was a kapu subject—something forbidden, off-limits, so consecrated as to be barred.

It took several more failed drafts and variations on a Night Marcher story to reorient my thinking to that of opening a door rather than slamming one shut. I do not believe that every aspect of Hawaiian narratives must be accessible to all readers, but I do think we are capacious enough a culture to afford a glimpse into where we come from and where we are going.

Like so many other groups that have been marginalized and peripheried in service of the white experience, we Hawaiians are rarely afforded the opportunity to tell our own stories. It’s 2023, and I regularly encounter people who do not know the difference between a person who lives in Hawaiʻi and a kanaka maoli, a person of native Hawaiian ethnicity (both are often incorrectly called Hawaiian). I try my best to be sympathetic to the ignorance, though inwardly I am enraged. Scan any bookshelf in a bookstore, do the smallest amount of author research, and you will find there are dozens of stories of Indigenous Hawaiian lives written by non-Indigenous writers. My choice to write this collection was also a move toward reclamation, to offer one kanaka maoli perspective among those of non kānaka.

So I started the story again, this time with the intention of laying bare all the anxieties and barriers that held back my fiction. As a meta entry point, I was introduced to the character Aiko, with whom I shared both a heritage, a literary passion, an ʻaumākua, and an overwhelming sense of dread surrounding the writing of the Night Marchers. Aiko’s tūtū had given her a fair warning—do not write about anything kapu. Do not write about the Night Marchers. And Aiko did it anyway to what could be interpreted as her own detriment. The story investigates what it means to write responsibly about something sacred; it was the only way I could access the sacredness of the Night Marchers.

Yet even as the story made its way through edits, self-doubt clung to me like the humidity of my homeland, and the burden of responsibility to do right by the Night Marchers story weighed on me. It wasn’t only the Night Marchers but also the story of Pelehonuamea and Kamapuaʻa, the story of Nānāhoa on Molokai, the stories our kūpuna so graciously passed down to my generation for safe keeping. I had believed, naively, that the only way to keep a story safe is to keep it guarded, lest I risk making room for failure to creep onto the page. If I couldn’t guarantee I could get the story “right,” perhaps I should not be writing it?

What I realized while struggling to write about the Night Marchers was that despite my awareness that the idea of a monolithic “Hawaiian” experience is nonsense, I was seeking nonetheless to create one on the page. All my fears and insecurities surrounding the writing of ancestral moʻolelo focused on getting things “right”—our people, or places, our stories, our traumas, our triumphs. This bent toward accuracy was a western concept, and did not account for the capaciousness of our stories. There is no one way to tell the vibrant, expansive tales of kānāka ʻōiwi. The only way to dismantle the perception of a monolithic Hawaiian experience is to uplift a multitude of Hawaiian stories crafted by a multitude of Hawaiian writers.

In the story, Aiko is a Hawaiian writer. Like me, she followed an impulse to tell the stories of her ancestors, but her intentions were sour, and she did not heed the words of her tūtū to write responsibly of such sacred tales. At the blow of the conch shell, the pound of the pahu drum, the smell of kindled torches, the whisper of ʻoli, Aiko did not bow for huakaʻi pō, she did not lie prone in their path or avert her eyes. I’d like to think I have learned from her mistakes.

__________________________________

Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare: Stories by Megan Kamalei Kakimoto is available from Bloomsbury Publishing.