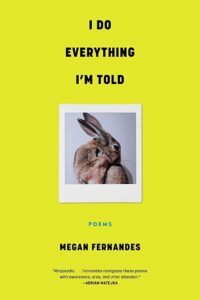

Megan Fernandes on the Literary Uses of a Room

"Rooms are springboards for time and time is for the poets."

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

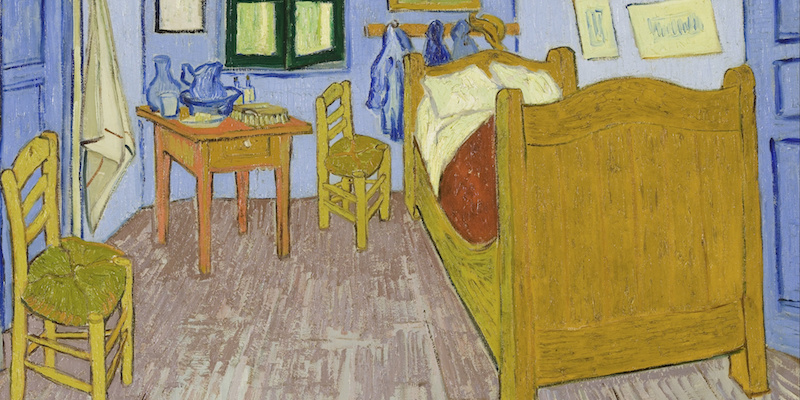

I dream in rooms. I wake up and assess how many staircases, ladders, kitchens, bathtubs, and mattresses have appeared. I look up their meaning, invite my own interpretation. I am easily enchanted by walking into a hotel lobby, taking in the furniture and side tables and light fixtures and sounds. It doesn’t even have to be a nice hotel — any gruff steward of a gritty yet full of “character” place will charm me.

I’m compelled by a dimly blinking neon motel vacancy sign. I love stories that take place in an opulent dining room, and I watch how the emotional lives of the dinner guests can spatialize into an atmosphere. I know that what happens in a basement can’t happen in an attic. I know that what is confessed in a bedroom is not nearly as desperate as what might be said in a hallway, on the way out, forever, that narrow passage of departure. I know why people gather in the kitchen at parties under the terrible fluorescence. It’s because the kitchen is church, the place of sensory ritual.

As a poet, this might seem like a novelistic affectation. But then again, rooms are springboards for time and time is for the poets. They provide jumping off and landing spaces for flashbacks and digressions. It’s fine if we are suddenly in Spain as long as we know we are tethered in a room, tucked cozily with our speaker, offering us the scene. A scene is itself a kind of room and a room is a useful constraint.

Rooms are springboards for time and time is for the poets. They provide jumping off and landing spaces for flashbacks and digressions.

In my new book, I Do Everything I’m Told, rooms become altars. In one poem called “I’m Smarter Than This Feeling, But Am I?” the speaker invents a beloved walking through the door while I smoke a cigarette on the balcony at a party and the stage is set. Everything else that occurs does so in slow motion because the points of distance have been established: the door and the balcony, the cigarette smoke and party guests between the speaker and the beloved.

In another poem, “Reunion,” we begin in plane and then Venetian cathedral and then end in a kitchen, washing plum tomatoes, watching the water rushing out of the faucet. The water outside in the canals of Venice becomes the water in the sink. The inside of the church with swollen madonnas come into view at the end of the poem just within sight of the kitchen window. The rooms and elements act as a kind of parenthesis. They create the claustrophobia and longing and lay out the possibilities of different fates.

In Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, the character Cora hides in a small attic for several months in North Carolina to avoid getting caught and potentially publicly executed for being a runaway. The reader squeezes into the tiny space with her, follows her eyeline out to the public square where she witnesses the brutal execution of Black people who had been enslaved and attempting freedom. The attic becomes telescopic, a micro-scale of the violence and because of the room’s smallness, the reader feels an intimacy both with the vast interiority of Cora made even more vast because of the circumstances of her living quarters, but also with the terrifying proximity she has to the threat against her life just outside the room.

In The Virgin Suicides, death is infrastructural. The sisters choose different methods, but also different rooms in which to end their lives and this is meant to tell us something about them. One sister in an attempted suicide, chooses the tub in the bathroom. Another sister successfully kills herself in a car in the garage. And yet another hangs herself in a room full of balloons. It is this compartmentalization of the same devastating event under one roof, narrated from those mostly outside the house itself, that gives the reader of sense of simultaneous doom. There is doom in the kitchen. In the bathroom. In the bedroom. In the garage. One sister finally kills herself by throwing herself out the window, breaking the voyeurism of their demise, finally breaking the “room” itself.

Rooms are also the spaces of epiphanies. Bertha Young of Katherine Mansfield’s short story, Bliss, is one of the most “vital” bodies of modernist literature. She is literally a spasming, leaking, energetic force able to mediate the matter of her environment from furniture to pear trees. Bertha describes herself and others as “hysterical,” “absurd,” “zestful,” and “passionate.” She and her fellow characters are in different states of “jumping,” “running,” “seizing,” “crying,” “shivering,” “blazing,” and “quivering.” The nervous, staccato energy with which Bertha moves from room to room and person to person indicates not only a restlessness, but an acknowledgement of some spectral presence, some amorphous state called Bliss. Objects seem to react to Bertha’s blissful adrenaline, animated by her field of energy. Or rather, they seem to share the same ecological space, sensitive to energy and vitality.

In one passage, Bertha goes to rearrange cushions in the drawing room only to relish in the face that “the room came alive at once. As she was about to throw the last one she surprised herself by suddenly hugging it to her, passionately, passionately. But it did not put out the fire in her bosom. Oh, on the contrary!” (Mansfield). Bertha’s exaggerated state in Mansfield’s story is networked to the furniture and objects around her, but it is not just that this amorphous state of vitality has permeated the environment, but rather, it calls us to question Bliss, as a spatial, traveling, structureless, whispering, haunting, glowing, and arousing state.

Rooms contain and break, imprison and liberate. I often think about the fact that the last chapter of Ulysses is the only one that takes place entirely indoors. In a bedroom with Molly narrating in eight sentences her own version of events. I often think about the rumor that went around about Beloved being a child that was raised in a dark room in Toni Morrison’s Beloved. The glassware on the table matters in order to set a mood, to give us a sense of how our speakers and characters live, and what triangulates their world when other people arrive into the space and disrupt the worlding.

___________________________

I Do Everything I’m Told by Megan Fernandes is available now via Tin House.

Megan Fernandes

Megan Fernandes is the author of Good Boys, and a finalist for the Kundiman Poetry Prize and the Paterson Poetry Prize. Her poems have been published in The New Yorker, Kenyon Review, The American Poetry Review, Ploughshares, The Common, and the Academy of American Poets, among others. An associate professor of English and the writer-in-residence at Lafayette College, Fernandes lives in New York City.