Meeting a Crying Need: How the Women of the Jane Revolutionized the Abortion Conversation

Laura Kaplan on the Hidden History of Pre-Roe Abortion

During the four years before the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision legalized abortion, thousands of women called Jane. Jane was the contact name for a group in Chicago officially known as The Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation. Every week desperate women of every class, race and ethnicity telephoned Jane. They were women whose husbands or boyfriends forbade them to use contraceptives; women who had conceived on every method of contraception; women who had not used contraceptives.

They were older women who thought they were no longer fertile; young girls who did not understand their reproductive physiology. They were women who could not care for a child and women who did not want a child. Some women agonized over the decision, while others had no doubts. Each one was making the best decision about motherhood that she could make at the time.

Organized in 1969, Jane initially counseled women and referred them to the underground for abortions. Other groups offering the same kind of crucial help took shape at this time throughout the country. But Jane evolved in a unique way. At first the women in Jane concentrated on screening abortionists, attempting to determine which ones were competent and reliable. But they quickly realized that as long as women were dependent on illegal practitioners, they would be virtually helpless.

Jane determined to take control of the abortion process so that the women who turned to Jane could have control as well. Eventually, the group found a doctor who was willing to work closely with them. When they discovered that he was not, as he had claimed to be, a physician, the women in Jane took a bold step: “If he can do it, then we can do it, too.” Soon Jane members learned from him the technical skills necessary to perform abortions.

Whenever individuals gain access to the tools and skills to affect the conditions of their own lives, they define empowerment.

As members of the women’s liberation movement, the women in Jane viewed reproductive control as fundamental to women’s freedom. The power to act had to be in the hands of each woman. Her decision about an abortion needed to be underscored as an active choice about her life. And, since Jane wanted every woman to understand that in seeking an abortion she was taking control of her life, she had to feel in control of her abortion. Group members realized that the only way she could control her abortion was if they, Jane, controlled the entire process. The group concluded that women who cared about abortion should be the ones performing abortions.

None of the women who started Jane ever expected to perform abortions. What they intended was to meet what one member called “a crying need.” That need gradually led them to radical actions. Their work was not based on a medical model, but on how they themselves wanted to be treated. When a woman came to Jane for an abortion, the experience she had was markedly different from what she encountered in standard medical settings. She was included. She was in control. Rather than being a passive recipient, a patient, she was expected to participate. Jane said, “We don’t do this to you, but with you.”

By letting each woman know beforehand what to expect during the abortion and the recovery stage, and then talking with her step by step through the abortion itself, group members attempted to give each woman a sense of her own personal power in a situation in which most women felt powerless. Jane tried to create an environment in which women could take back their bodies, and by doing so, take back their lives. When I joined Jane, the group had managed to give women not only psychological control, but also freedom from the financial extortion that illegal abortionists subjected them to. Jane charged only the amount necessary to cover medical supplies and administrative expenses. And no woman was turned away because of her inability to pay.

Whenever individuals gain access to the tools and skills to affect the conditions of their own lives, they define empowerment. Our actions, which we saw as potentially transforming for other women, changed us, too. By taking responsibility, we became responsible. Most of us grew stronger, more self-assured, confident in our own abilities. In picking up the tools of our own liberation, in our case medical instruments, we broke a powerful taboo.

That act was terrifying, but it was also exhilarating. We ourselves felt exactly the same powerfulness that we wanted other women to feel. We came to understand that society’s problems stemmed from imbalances in power, the power of one person over another, teacher over student, doctor over patient. The weight of the authority and the expert was inherent in the position, no matter who held it. Jane, through the group’s practice, challenged institutionalized authority and tried to redress these imbalances of power.

But the politics of power, which we recognized so clearly in the larger society, were ironically mirrored in our own internal dynamics. While Jane succeeded in giving control to the women in need of abortions, the group was not as successful in sharing control among its own members. A hierarchy of knowledge developed—knowledge of medical technique, of crucial problems and critical decisions. Those who withheld the knowledge frequently justified their actions by citing the need for secrecy to protect the group from exposure.

This was a valid argument in an era in which simply providing information about abortion was a criminal act. But necessary caution was not the only explanation. We discovered how difficult it was to resist reproducing those ordering structures which shape our society, even as we challenged many of their manifestations. Sometimes it seemed that our determination to empower the individual could find consistent expression only in our interactions with the women who turned to us for help. To them, we gave as much information as we could uncover about the workings of their bodies and what they could do to foster their own health.

Jane developed at a time when blind obedience to medical authority was the rule. There were no patient advocates or hospital ombudsmen, no such person as a health consumer. Few women understood their reproductive physiology or had any idea where to get the information they needed. The special knowledge doctors had was deliberately made inaccessible, couched in language incomprehensible to the lay person. We did not have a right to it.

It was only in late 1970 that Our Bodies, Ourselves, the first in a wave of self-help health books, was published. Now many of us know that we can get the medical information we need in a library or bookstore, but this was unheard of twenty-five years ago. Still, finding health care that is not only adequate and affordable, but also respectful, is, for most of us, a continuing struggle.

To force a woman either to carry an unwanted pregnancy or to venture into a dangerous underground was considered morally indefensible. Women were dying because they were denied the ability to act on their own moral decisions.

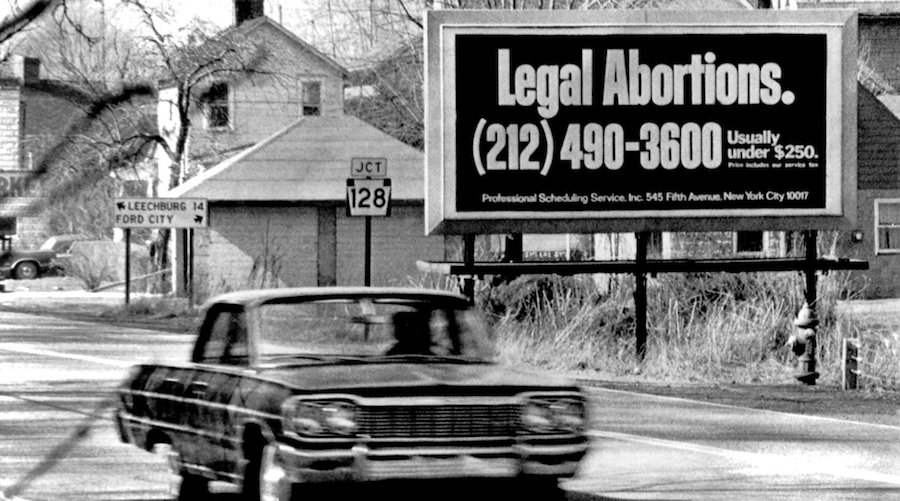

In the late 1960s others outside the women’s liberation movement were working to change abortion laws. There were legal scholars and organizations like the Association for the Study of Abortion in New York; population control groups like ZPG (Zero Population Growth), and NARAL (then, The National Association for Repeal of Abortion Laws) that supported legislative change and challenged the constitutionality of laws in the courts. They directed their efforts at the established channels of institutionalized authority, but their gains were only modest until the women’s liberation movement mobilized women across the country who accelerated the struggle with their anger.

Women’s liberation groups organized speak-outs at which women testified to their own illegal abortions. They marched and demonstrated and disrupted legislative hearings on abortion that excluded women. They demanded that women, the true experts on abortion, be heard and recognized. They brought abortion out of the closet, where it had been shrouded in secrecy and shame.

But the women’s liberation movement did more than place abortion in the realm of public discourse. It framed the issue, not in terms of privacy in sexual relations, and not in the neutral language of choice, but in terms of a woman’s freedom to determine her own destiny as she defined it, not as others defined it. Abortion was a touchstone. If she did not have the right to control her own body, which included freedom from forced sterilizations and unnecessary hysterectomies, gains in other arenas were meaningless. These issues were addressed not only in political terms, but also in moral terms. To force a woman either to carry an unwanted pregnancy or to venture into a dangerous underground was considered morally indefensible. Women were dying because they were denied the ability to act on their own moral decisions.

While the public struggle was underway, every day women who tried to find abortions put their lives at risk. Their suffering could not be ignored. Women’s groups and networks of the clergy organized to meet these women’s immediate needs. Based on a moral imperative, Howard Moody, a Baptist minister, founded the first clergy group, the New York Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion. He encouraged clergymen throughout the country to set up similar networks to help women get safe abortions. These clergy groups, with the moral standing of organized religion, played a public role, announcing their work in the newspapers, framing the issue in moral terms and advocating for legislative change.

Both the clergy and women’s liberation groups sought out competent abortionists, negotiated the price, raised money to pay for abortions and counseled thousands of distraught women. Not only did they help women but, by breaking the law, they also undermined it. They followed the tradition of the Underground Railroad which defied another immoral law, the Fugitive Slave Act, and helped to undermine the institution of chattel slavery. Like the scores of people who were part of the Underground Railroad, the stories of those who participated in these referral services are part of our hidden history.

________________________________

From The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service by Laura Kaplan. Reprinted by permission of Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Laura Kaplan.

Laura Kaplan

Laura Kaplan was a member of Jane and founding member of the Emma Goldman Women’s Health Center in Chicago. After moving to rural Wisconsin, she attended home births as a lay-midwife and established a shelter-based program for battered women. When she moved to the East Coast, she worked as an advocate for nursing home residents and was the managed care project director for Citizen Action of New York. She is on the board of the National Women’s Health Network and has been involved in a variety of community projects.