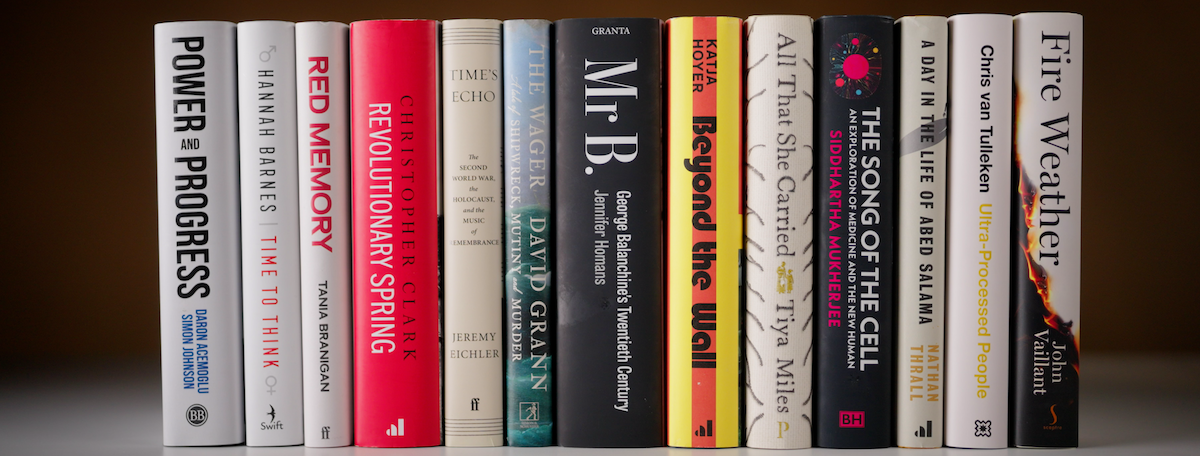

Meet the 13 Writers on the 2023 Baillie Gifford Prize Longlist

Interviews with Some of Today’s Finest Writers of Nonfiction

This year’s longlist for the Baillie Gifford Prize spans the globe and spans centuries, encompassing a diverse selection of some of the best nonfiction published in 2023. With the help of archives and interviews, the books on this year’s longlist examine topics ranging from the Chinese Cultural Revolution to the impact of ultra-processed foods on human health. Below, the longlisted authors answer some of our questions and tell us a bit about their books and the research and writing processes that went into them.

*

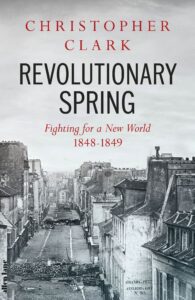

Revolutionary Spring: Europe Aflame and the Fight for a New World, 1848-1849 by Christopher Clark

How did you conduct your research?

I read and read and read and read in books, newspapers, pamphlets, memoirs, and letters, until I could hear the voices of the people of 1848 as I went to sleep. The slowing of everything during the COVID pandemic enabled me to read more deeply and thoughtfully than would otherwise have been possible. The hardest part of the research was devising a narrative structure that would do justice to such a sprawling subject. I filled many A3 pages with swirls of scrawl before I found something that seemed to work.

What do you think is the most enduring moment from the tumultuous events of 1848 on Europe, and how it shaped the Europe we know today?

For those who took part in it the memories of the spring of 1848 lasted as long as life itself. The euphoria, the falling away of fear, the sense of history in motion, the experience of immersion in a collective self—decades later people could remember these moments as if they had only just happened. The parliaments and constitutions of 1848 are less deeply etched in European memory, but they were among the most durable legacies of the upheaval. Looking outside Europe, the formal abolition of slavery in the French Empire, an achievement of the Provisional Government established in Paris February 1848, created a new point of departure for the enslaved people of the French colonies, even if social and racial equality would take generations to accomplish.

In your exploration of the events of 1848 in Europe, which historical figures stood out as particularly significant or emblematic of the sweeping changes and challenges faced by societies during this period of upheaval?

Hundreds come to mind, but I was particularly struck by the women who wrote as witnesses of the events of 1848. Women were present everywhere in that year—as fighters on the barricades, as newspaper editors and as protestors on the streets of the European cities, yet they were excluded from the new ministries and parliaments (except as spectators in the galleries), denied the right to vote and barred from membership of most political clubs and associations. Perhaps for that reason, their writing on the events of that year is unique in its detachment, its willingness to grant all protagonists a share of the writer’s sympathy and to replace polemic with the balanced analysis of complex conflicts. Marie d’Agoult, Cristina di Belgiojoso, Eugénie Niboyet and Margaret Fuller (among many others) all embody these virtues.

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder by David Grann

How did you conduct your research?

I spent more than half a decade doing research, combing through archives. Miraculously, there is a wealth of documents, including logbooks and journals, that survived the disastrous expedition.

To better understand what the castaways had endured, I also made a trip, in a small wood-heated boat, to the remote island off the Chilean coast of Patagonia, where they had been stranded. The island remains wild and desolate, and after visiting it I could finally comprehend why a British officer had described it as a place where “the soul of man dies in him.”

What do you think motivated the thirty men who landed on the coast of Brazil to paint themselves as the heroes?

We all tend to shape our stories, trying to emerge as the hero of them. But for these men the stakes were existential. They faced the prospect of a court-martial for the crimes they had allegedly committed on the island. If they failed to tell a convincing tale, they could be hanged.

What does The Wager reveal about the complexities of human behavior and justice in extreme circumstances?

It highlights just how fragile the human condition is. The island where the castaways were marooned was like a laboratory testing them under brutal elements; inevitably, it would reveal the men’s true nature—both the good and the bad.

Beyond the Wall: A History of East Germany by Katja Hoyer

How did you conduct your research?

I was in a truly enviable position for a historian: I had millions of sources available to me. My subject, East Germany, still sits comfortably within the realms of living memory. Alongside documents, letters, memoirs and diary entries, I could tap into the minds and memories of the people who lived this history. The many interviews I conducted with former citizens of East Germany added a colorful array of nuances and anecdotes to a story that has often been depicted in black and white.

How did the forming of East Germany change the fabric of the nation’s identity?

The division of Germany into two states between 1949 and 1990 has carved a deep mark into the nation’s identity. Those forty-one years were longer than the eras of the First World War, the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany combined. During those decades, Germans East and West of the Iron Curtain lived different lives while pointing a terrifying arsenal of weaponry at one another. Then in 1990, everything changed for East Germans while West Germans continued largely as before. These contrasting experiences continue to mark the political, economic and social landscape of Germany today.

Will we continue to see the impact of a divided Germany or is that all in the past now?

It was a mistake to assume that East Germans would naturally adopt the lifestyles, opinions and habits of their Western counterparts when their state disappeared virtually overnight on October 3, 1990. Neither were they immediately seen as equals or placed on a level playing field in terms of life chances and opportunities. Political fractures such as Germany’s reunification in 1990 make for convenient points on historical timelines, but they don’t reflect the realities lived by people whose life stories straddle them. The impact of Germany’s division will be with us for some time yet. Its rifts will take time and empathy to heal.

Mr. B: George Balanchine’s 20th Century by Jennifer Homans

How did you conduct your research?

Balanchine has been one of the greatest intellectual, emotional, and spiritual encounters of my life. The research was an intense decade-long journey that really began a lifetime ago when I was a teenager and first set foot in a dance studio, saw and performed Balanchine’s dances, and watched him work. How could I have known then that the project of knowing him would take me to archives and places and people in Russia, Georgia, and across Europe and America; into the history of war, art, music, literature, jazz and African American dance, all of which influenced him greatly; into philosophy, Orthodoxy, Sufism, exile, the Cold War, and so much more.

I was especially interested in the testimony of dancers and I interviewed over 200 people who had worked with or known Balanchine and the other supporting characters in the book. His dances did not exist without dancers, and their presence—physical, emotional, and intellectual—profoundly shaped his life—and my account of him.

But testimony and memory are not history, and I also did extensive archival research in Russia, Georgia, and in cities across Europe and America. Balanchine himself destroyed the evidence of his life as he went, and recovering him meant reading everything that was left, from letters, sketches and musical scores. to credit card receipts and passport applications. I also walked Balanchine’s path, and followed him to dance studios, theaters, and museums; hospitals, Orthodox churches, restaurants and hotels; places where he loved, and places where he wept.

I read what he read: Cervantes, Goethe, Shakespeare, Ovid; Pushkin, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Chekhov, Gogol, Bulgakin; Mysticism, Neoplatonism, Spinoza, Sufism; I studied art that he drew on, from Russian Icons, to Renaissance painting, and the surrealists. I listened: to Bach, Mozart and Tchaikovsky; Stravinsky, Ives, Hindemith, Xenakis. And of course, I watched, and danced, his dances.

How far do you think the twentieth century shaped Balanchine’s being and relationship to his work?

Profoundly. I subtitled the book “George Balanchine’s 20th Century” because he absorbed into his dances the century he lived through. He experienced WW1, the Russian Revolution, WW2 and the Cold War; he was in Berlin and Paris in the 1920s, and landed in NY in 1933 in the middle of the Depression. He lived through hunger and dispossession; statelessness and exile; epidemics and illness (he should have died of TB). He worked on Broadway, in Hollywood, and staged opera, theatre and the circus, and in 1948, he cofounded the New York City Ballet where, with his dancers, he made some of the strangest and most glorious dances to grace the modern stage.

I also subtitled the book “George Balanchine’s 20th Century” because his dances were his 20th Century—the one he created in art.

It took me 600 pages to answer this question, which is truly at the heart of the Mr. B.

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake by Tiya Miles

How did you conduct your research?

All That She Carried is the first book on Ashley’s Sack, a unique artifact of the African American experience that illuminates key themes in this history, such as enslavement, loss, family, motherhood, love, perseverance, artistry, and migration. While other scholars have conducted research on the sack or used it as an illustration of Black family separation or of radical visual self-representations, no one had before produced a full-length study of the artifact or its keepers. Researching the sack presented me with numerous and at times seemingly insurmountable challenges because the embroidered sack is the only known record of Rose and Ashley’s story. However, this documentary deficit proved to be an unexpected benefit because it necessitated the construction of a different kind of history, which I have come to think of as history in a poetic mode. This mode does not reject scholarly methods of historical investigation. Rather, it enlarges them by looking for a range of atypical sources and by offering interpretations that reach for deeper understandings of the experiential and emotional facets of historical life. The lack of traditional sources pushed me to think creatively about the relationship of early Black history to the archives, innovative archival practices, and experimental ways of narrating histories of Black women and other marginalized groups. Because the documentary record for this family is scanty prior to 1900, genealogical and biographical links in the book are speculative. In the book, I expose the inability to recover full and precise information about this family and many families that suffered enslavement, and I dwell on this difficulty as a meaningful part of the story.

How is the theme of memory illuminated in the book?

In the book, I consider how objects—especially objects explicitly linked to stories—have a special capacity to contain and revive memory in human experience. The delicate embroidery on the sack represents a family memory of sorrow and resilience that might have been lost if not for the carrying capacity of that bag. While doing this work, I was conscious of how my book about the sack is itself an object that helps to preserve public memory about a collective past. I was taken by this sense of doubling, or echoing, in the project.

A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy by Nathan Thrall

How did you conduct your research?

The seed of this book was planted on the day of the school bus crash, which took place not far from my home in Jerusalem. The kindergartners and teachers on the bus live just two miles from my apartment, but behind an imposing, 8-meter-tall concrete wall that encircles their community. Cut off from the heart of the city in which they grew up and crammed into a dense urban ghetto, they are forced to drive on narrow, dilapidated streets with no lanes, sidewalks, or police presence, and to wait in long lines at a military checkpoint to get to their schools, jobs, and hospitals—all of this in plain view of the elegant campus of Israel’s most prestigious university. The consequences of segregating and neglecting these people came into sharp relief when tragedy struck on the other side of the wall. Like many residents of Jerusalem, I drove by that walled-off enclave every week, hardly noticing it. But after the accident I couldn’t stop thinking of the children and the families who share this city with me, and what a different world they have been forced to live in. It wasn’t until years later, when I had the time to devote myself to writing a book, that I began in-depth research on the collision, sifting through police reports, court documents, and audio and video recordings. My research expanded from there, as I spoke to more and more Palestinian families whose lives were destroyed by the event, and to Israeli Jews whose own paths intersected with it. It was important to me that the book tell the personal stories of both Palestinians and Jews; finding the right characters took considerable digging. But the truth is that many of the most important discoveries came by chance. A close family friend turned out to be a distant relative of one of the parents, Abed Salama. As soon as I met Abed and heard his story, I knew he would be at the center of this book. Over the next four years, he and I spent so much time together that I came to feel like an honorary member of his family. Abed and a number of other characters shared their rawest emotions with me, in some cases revealing thoughts, feelings, and memories that they had kept from their own spouses. I knew I had a tremendous responsibility to do right by the trust they bestowed on me.

How does your book interweave the stories of Jewish and Palestinian characters with the journey of Abed and Milad, the book’s protagonists?

The book tells the story of Abed and his son Milad, but also of a teacher who sacrificed herself to rescue her students, a bystander who heroically entered the burning bus to pull out dozens of children, a settler paramedic who had witnessed unimaginable horrors in the past but was haunted and traumatized by the scale of this tragedy, and two desperate mothers who each hoped to claim the same severely injured boy as their son. By delving into the lives and backgrounds of the characters, the book ended up ranging far beyond the immediate present of the accident and forming a kind of intimate, multigenerational history of Palestine and Israel as refracted through these individuals’ families and memories. Once I decided that the book would essentially follow the chronology of the day, the structure began to fall into place. One of the great challenges was to interweave two different timelines: on one hand, the day of the crash and the order in which each protagonist intersected with it; on the other, the deep history of Israel-Palestine.

Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson

How did you conduct your research?

We read a lot of history, looking at past big shifts in technology. We combined these stories with insights from our decades of academic research to make sense of it all—and to build a coherent narrative.

How do you envision this book and your proposed strategies being used in the future when developing new technologies to ensure shared prosperity?

We are encouraged that people are starting to rethink what we should expect from technology, what “automation” means, and how to ensure we create more good jobs. We hope that the idea of using generative AI to make all workers more productive—rather than replacing and sidelining workers—gives readers a new perspective on what future can be created.

What case study from the past do you think best demonstrates how the path of technology can be brought under control?

We like the advent of railways in the 1830s and 1840s. This was a symbolic moment of change in the Industrial Revolution, with the focus shifting from automation and heavy-handed surveillance to an effort to increase the productivity of all workers. The benefits were felt throughout the economy, and wages started to rise across the board.

Time’s Echo: The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance by Jeremy Eichler

How did you conduct your research?

I conducted extensive archival research, which was a journey all its own that took me to five countries and to many places intimately connected to the history at the heart of the book. I ultimately chose to write about several of these research trips in Time’s Echo itself, with the hope of bringing readers with me to these sites and conveying something of the feel of these landscapes, the experience of being there. I thought often of a comment from the scholar and artist Svetlana Boym, who wrote that excavating the past requires “a dual archaeology of memory and of place.”

This book of course also stands on the shoulders of the work of many specialists from different fields. It could not have been written without the benefit of these rich bodies of secondary literature produced by biographers, historians, and other scholars from a number of disciplines.

Once I had completed my research, the next question was what to do with it. A book on these topics could be approached in the manner of a traditional academic study, but I did not want to write only for readers with specialized knowledge of these subjects, or only for people who already knew they cared about classical music or about the history of this period. Time’s Echo does offer perspectives and new research that I hope will feel intriguingly fresh for those groups of readers, but it ultimately becomes a much broader project. It is a book not just about the music of memory but about the memory of music—that is, an exploration of what art can help us recover and remember. I do hope this approach will resonate with a much wider audience. At this deeper level, the book is an invitation to grapple with the legacies of history, to find new ways of living with the ghosts of the past, and to renew or reimagine the presence of art in our lives today.

Is music particularly able to communicate the unspeakable?

Yes. But the meaning of that “yes” depends entirely on what is meant by the word unspeakable. In the nineteenth century, this idea—music’s special ability to communicate feelings, soul states, and inner truths that lie beyond the province of language—was a favorite trope of Romantic writers and other artists. And they were essentially right. We can be deeply moved by a piece of music that has no words, and keenly aware that it has expressed something powerful yet still untranslatable. A painting can do that too of course. But music does it differently.

In our own time, the question comes to mean something else entirely: can music describe the unfathomable barbarism of two world wars and the Holocaust. Of course not in any complete sense, but it can signal what language cannot, it can make moments in the distant past feel urgently alive again; it can burn through what the survivor Jean Améry once called “the cold storage of history.”

Is music uniquely capable doing these things? I do think it possesses some special and deep affinities with memory itself—and I explore that terrain in Time’s Echo. But this should not become some kind of competition. Each art form has its own distinct way of gesturing toward, indicating, summoning the contours of the modern unspeakable. They peer from different angles into the same abyss.

Right now, for me at least, questions like these feel particularly timely and even urgent. Not only are echoes from this period sounding all around us, but we have entered the twilight of living memory. The generation that survived the years of the Second World War and the Holocaust is fading by the day, and it therefore seemed like an important moment to ask how art in general—and music in particular—can serve as another bridge to the past. I was inspired by one of Theodor Adorno’s less frequently quoted comments about art after Auschwitz: “Because the world has outlived its own demise, it needs art as its unconscious chronicle.”

Time to Think by Hannah Barnes

How did you conduct your research?

Some of the research had been done before I signed the deal with Swift Press to write Time to Think—while making several films and writing articles on this topic for BBC Newsnight and the wider corporation. But ultimately this ended up being a very small amount of the overall research conducted. I’m not sure I can list everything that went into the book, but I can give a taster. I went through all the documentary material I could find in the public domain: going though every set of board minutes for the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, every Freedom of Information request, and press cuttings going back to the service’s beginning in 1989, for example. I read all the major academic papers that form the evidential basis for gender affirmative medical care in young people and submitted several Freedom of Information requests of my own. I contacted more than 60 clinicians who had worked directly with young people attending the Tavistock’s Gender Identity Development Service—hoping to gain a breadth and depth of accounts based on direct experience. I did the same with young people who had attended the service. I followed key legal cases live and spoke with as many people as I could with experience of both GIDS and the wider Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust. In the course of this, many were kind enough to share internal documents with me, as I gained their trust.

How different did you find writing a book from writing for a news program?

I was not at all prepared for what writing a book would entail! In some ways it was similar: taking huge amounts of information, sorting it and transforming it into a clear narrative; writing to a deadline; checking and rechecking facts and sources. But, overall, it was very different to writing for a news program, or factual documentary. For starters, it is an exceptionally lonely experience. In broadcasting you are almost always part of a team, even if it is a small one. You can bounce ideas off each other or simply let off steam. Writing a book is very much a lone project, even though I received enormous amounts of support from friends and family. Secondly, the timescale involved. Although I have generally worked on long form journalism, any given film of radio documentary might take weeks or even a couple of months, but not months on end. There was something different about the intensity too. With a Newsnight film for example, we tend to work very long hours in the days running up to transmission, but thankfully that spell is relatively brief. While writing, I experienced that level of intensity for months. All while looking after a newborn baby! I am used to working to deadlines—and I met mine for submitting the manuscript—but it took enormous discipline to divide a longer amount of time into milestones that had to be met so that I could deliver the book. And then there’s the depth of research. All my broadcast work is rigorously researched. It is double sourced at a minimum, checked, and re-checked. But the quantity of research required to fill 375 pages, and be seen as credible on such a controversial topic was very different. I wanted to be utterly transparent about where all the information had come from; that’s why there are 60 pages of references.

Red Memory: The Afterlives of China’s Cultural Revolution by Tania Branigan

How did you conduct your research?

I travelled across the country to visit museums and other sites but most of all, to meet survivors and spend hour after hour listening. What unites all the people in Red Memory is that they chose to remember when everyone else preferred to forget. I wanted to understand not just what happened to them, but how they saw it all; to be led, firstly, by what they chose to tell me, and how they told it, before delving deeper and asking them more. In most cases I met them multiple times, over months and years, and often, their stories overlapped. That allowed me to build up a much richer and more comprehensive picture of the era and what it means to people today—whether their overwhelming feeling is guilt, trauma or even nostalgia. Then there are all the people who aren’t mentioned directly in the book but whose experience informed it in so many ways. Those I met included Mao’s personal photographer, who captured both iconic images of the Great Helmsman and his private family moments—but then, like so many, was hounded in the Cultural Revolution. Several of them have died since we spoke; I was privileged to capture a part of history that is slipping away very fast.

Of course, I also benefited immensely from the wealth of research that’s been done by scholars and other researchers, both outside China and within. My reading stretched from personal memoirs and fiction through to in-depth studies of everything from Mao badges to mass killings. I hope that readers of Red Memory will turn to some of those books too.

In Red Memory, you delve into the personal stories of individuals who lived through the Cultural Revolution and its enduring impact on Chinese society. What was the most compelling or surprising story from your research that sheds light on how this tumultuous period continues to shape China today?

In political terms it’s hard not to see today’s China—in particular Xi Jinping’s concentration of power and axing of term limits—in light of his personal experience of the era, when his family was persecuted and he spent seven years laboring in bitter rural poverty. In psychological terms, the ongoing toll is encapsulated by the apparently mild-mannered young man who suddenly published a graphic account of killing one of his tutors. It was only after his family began seeing a psychotherapist that he learned that his father had watched as his grandfather was murdered by Red Guards. It speaks volumes about the secrets that families still keep, and their cost. The past refuses to be left behind.

What shocked me most, however, were the growing parallels between the Cultural Revolution and what I saw as I was writing—both in China and in the west.

Ultra-Processed People: The Science Behind Food That Isn’t Food by Chris Van Tulleken

How did you conduct your research?

This book has been gestating for six years and involved investigating the food industry around the globe. I’ve seen first-hand how the UPF industry, comprising some of the most powerful corporations on earth, has commodified the ill health of our planet’s most disadvantaged whilst working as a doctor and academic in Brazil, South Asia and Central Africa. However, some of the most interesting research was speaking to food industry insiders who explained the extent to which money is the only incentive within the food system. It revealed how these companies will be unable to change unless their activities are regulated by governments.

Based on your research, how dangerous could ultra-processed food become for our society?

Poor diet has overtaken tobacco as the leading cause of early death on planet Earth. It causes not just weight gain and obesity but also cancer, inflammatory disease, malnutrition, metabolic illness, mental health problems and dementia and it drastically shortens life expectancy. It is the new tobacco, and we should consider the corporations that make it as the new tobacco industry.

Do you believe it is possible for us to ever have a true, holistic grasp of what we are really eating and how it affects us?

Yes. For hundreds of millennia, humans going back to pre-history have had a very sophisticated understanding of what comprises a healthy diet. That knowledge has been destroyed by the marketing and proliferation of an ultra-processed diet, comprising substances and made using processes that create products that no one can fully understand. If you want to understand food, speak to a good chef or a parent who cooks real food for their kids.

Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World by John Vaillant

How did you conduct your research?

Through every means of perception available to me: On-the-ground, in-person research and interviews; retracing the steps, work, and words of key characters, living and dead; extensive reading, watching, looking, listening, and smelling; following closely (via Twitter) the fields of science, business, petroleum, insurance, activism, and fire behavior; and, frankly, through dreaming, which gave me the narrative structure and psychic clarity to take on this daunting subject.

How is understanding the histories of the oil industry and climate science crucial to the future of addressing environmental issues?

We have arrived at this moment on a braided bridge of ambition, invention, good intention, and greed. The history of the oil industry offers a vivid, unvarnished lens through which to understand these complementary drivers. Climate science, meanwhile, offers a corrective: that is what you think you’re doing; this is what you’re actually doing. In this way, science serves as a reality check, but also as an objective guide to shaping, and possibly healing, the future.

The Song of the Cell: An Exploration of Medicine and the New Human by Siddhartha Mukherjee

How did you conduct your research?

The book was written over the course of a few years, but it is deeply connected to the foundation laid out during my medical school years—studying to be a cell biologist, an immunologist and an oncologist. The most challenging aspect was organizing the structure of the book to vividly convey its message to the audience.

Based on your research, how far could the study of cells take humanity?

Life without contemplating cells is inconceivable for any scientist. In the realm of medicine, we’re transitioning from the era of genetic research to the era of cellular exploration—a nascent science with a myriad of therapeutic potentials. However, alongside these possibilities arise ethical and philosophical inquiries, as we delve into the profound alteration of human bodies. It’s a consideration that demands reflection both as medical professionals and as societies.

How does the book mix biology with character study?

The history of cell biology is full of strong characters, and finding them was not hard. There is also a thread of personal history, involving my own work in the lab and my encounters with patients. The stories all touch directly on the underlying science, which allows the book to weave around its subject in a way that I hope feels right.