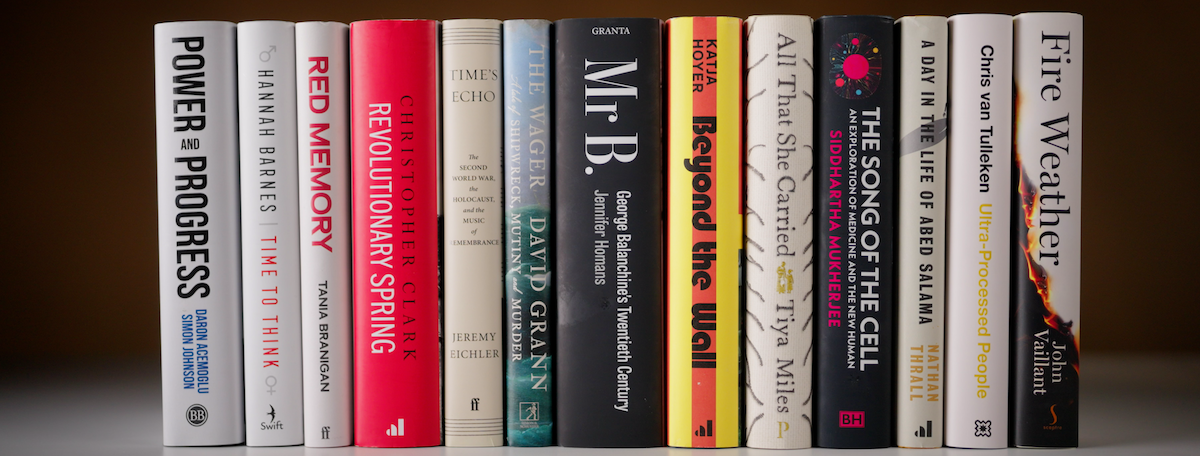

Meet the 13 Writers on the 2023 Baillie Gifford Prize Longlist

Interviews with Some of Today’s Finest Writers of Nonfiction

Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson

How did you conduct your research?

We read a lot of history, looking at past big shifts in technology. We combined these stories with insights from our decades of academic research to make sense of it all—and to build a coherent narrative.

How do you envision this book and your proposed strategies being used in the future when developing new technologies to ensure shared prosperity?

We are encouraged that people are starting to rethink what we should expect from technology, what “automation” means, and how to ensure we create more good jobs. We hope that the idea of using generative AI to make all workers more productive—rather than replacing and sidelining workers—gives readers a new perspective on what future can be created.

What case study from the past do you think best demonstrates how the path of technology can be brought under control?

We like the advent of railways in the 1830s and 1840s. This was a symbolic moment of change in the Industrial Revolution, with the focus shifting from automation and heavy-handed surveillance to an effort to increase the productivity of all workers. The benefits were felt throughout the economy, and wages started to rise across the board.

Time’s Echo: The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance by Jeremy Eichler

How did you conduct your research?

I conducted extensive archival research, which was a journey all its own that took me to five countries and to many places intimately connected to the history at the heart of the book. I ultimately chose to write about several of these research trips in Time’s Echo itself, with the hope of bringing readers with me to these sites and conveying something of the feel of these landscapes, the experience of being there. I thought often of a comment from the scholar and artist Svetlana Boym, who wrote that excavating the past requires “a dual archaeology of memory and of place.”

This book of course also stands on the shoulders of the work of many specialists from different fields. It could not have been written without the benefit of these rich bodies of secondary literature produced by biographers, historians, and other scholars from a number of disciplines.

Once I had completed my research, the next question was what to do with it. A book on these topics could be approached in the manner of a traditional academic study, but I did not want to write only for readers with specialized knowledge of these subjects, or only for people who already knew they cared about classical music or about the history of this period. Time’s Echo does offer perspectives and new research that I hope will feel intriguingly fresh for those groups of readers, but it ultimately becomes a much broader project. It is a book not just about the music of memory but about the memory of music—that is, an exploration of what art can help us recover and remember. I do hope this approach will resonate with a much wider audience. At this deeper level, the book is an invitation to grapple with the legacies of history, to find new ways of living with the ghosts of the past, and to renew or reimagine the presence of art in our lives today.

Is music particularly able to communicate the unspeakable?

Yes. But the meaning of that “yes” depends entirely on what is meant by the word unspeakable. In the nineteenth century, this idea—music’s special ability to communicate feelings, soul states, and inner truths that lie beyond the province of language—was a favorite trope of Romantic writers and other artists. And they were essentially right. We can be deeply moved by a piece of music that has no words, and keenly aware that it has expressed something powerful yet still untranslatable. A painting can do that too of course. But music does it differently.

In our own time, the question comes to mean something else entirely: can music describe the unfathomable barbarism of two world wars and the Holocaust. Of course not in any complete sense, but it can signal what language cannot, it can make moments in the distant past feel urgently alive again; it can burn through what the survivor Jean Améry once called “the cold storage of history.”

Is music uniquely capable doing these things? I do think it possesses some special and deep affinities with memory itself—and I explore that terrain in Time’s Echo. But this should not become some kind of competition. Each art form has its own distinct way of gesturing toward, indicating, summoning the contours of the modern unspeakable. They peer from different angles into the same abyss.

Right now, for me at least, questions like these feel particularly timely and even urgent. Not only are echoes from this period sounding all around us, but we have entered the twilight of living memory. The generation that survived the years of the Second World War and the Holocaust is fading by the day, and it therefore seemed like an important moment to ask how art in general—and music in particular—can serve as another bridge to the past. I was inspired by one of Theodor Adorno’s less frequently quoted comments about art after Auschwitz: “Because the world has outlived its own demise, it needs art as its unconscious chronicle.”

Time to Think by Hannah Barnes

How did you conduct your research?

Some of the research had been done before I signed the deal with Swift Press to write Time to Think—while making several films and writing articles on this topic for BBC Newsnight and the wider corporation. But ultimately this ended up being a very small amount of the overall research conducted. I’m not sure I can list everything that went into the book, but I can give a taster. I went through all the documentary material I could find in the public domain: going though every set of board minutes for the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, every Freedom of Information request, and press cuttings going back to the service’s beginning in 1989, for example. I read all the major academic papers that form the evidential basis for gender affirmative medical care in young people and submitted several Freedom of Information requests of my own. I contacted more than 60 clinicians who had worked directly with young people attending the Tavistock’s Gender Identity Development Service—hoping to gain a breadth and depth of accounts based on direct experience. I did the same with young people who had attended the service. I followed key legal cases live and spoke with as many people as I could with experience of both GIDS and the wider Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust. In the course of this, many were kind enough to share internal documents with me, as I gained their trust.

How different did you find writing a book from writing for a news program?

I was not at all prepared for what writing a book would entail! In some ways it was similar: taking huge amounts of information, sorting it and transforming it into a clear narrative; writing to a deadline; checking and rechecking facts and sources. But, overall, it was very different to writing for a news program, or factual documentary. For starters, it is an exceptionally lonely experience. In broadcasting you are almost always part of a team, even if it is a small one. You can bounce ideas off each other or simply let off steam. Writing a book is very much a lone project, even though I received enormous amounts of support from friends and family. Secondly, the timescale involved. Although I have generally worked on long form journalism, any given film of radio documentary might take weeks or even a couple of months, but not months on end. There was something different about the intensity too. With a Newsnight film for example, we tend to work very long hours in the days running up to transmission, but thankfully that spell is relatively brief. While writing, I experienced that level of intensity for months. All while looking after a newborn baby! I am used to working to deadlines—and I met mine for submitting the manuscript—but it took enormous discipline to divide a longer amount of time into milestones that had to be met so that I could deliver the book. And then there’s the depth of research. All my broadcast work is rigorously researched. It is double sourced at a minimum, checked, and re-checked. But the quantity of research required to fill 375 pages, and be seen as credible on such a controversial topic was very different. I wanted to be utterly transparent about where all the information had come from; that’s why there are 60 pages of references.