Measuring the Decline of America's First Company Town, One Crack at a Time

Lawrence Lenhart Offers a Very Personal Case Study in Rust Belt Decline

This essay originally appeared in Conjunctions: 68.

![]()

Winnipeg, Winnipeg: snowy, sleepwalking Winnipeg. My home for my entire life. I need to get out of here. I must leave it now. What if I film my way out of here? It’s time for extreme measures.

–Guy Maddin, My Winnipeg

In Pennsylvania’s Lower Turtle Creek Valley—where there are no longer turtles in the crick (for decades, I’ve checked), no turtle soup on its cafés’ menus either—a borough surrenders its castle. On a Saturday morning, the last contents of the turreted sandstone castle are dragged onto the lawn: three chairs from the old high-school auditorium, a big drum that belonged to the Polish Falcons, and an antique Westinghouse roaster stand (“calibrated to match the temperatures in your cookbook with super-super exactness”). I drive around the Castle once, twice, a few times more. The tally ticks upward. I’m in indefinite orbit.

For years, there has been a protracted campaign to resuscitate the glory of the old castle on the hillock, which for 95 years served as the Westinghouse Air Brake Company General Office Building. Now, just weeks after a rash of vandalism and weeks before the public option, the vacancy seems to dignify the Castle. That’s what I’m circling, witnessing, authenticating—its reset dignity. The Castle’s clock tower, which once signaled work shifts at the nearby Air Brake factory, has become a vestigial architecture. I discontinue my circuit of bygone industry, trying not to read the “Commerce Street” signage as ironic, and drive toward the decrepit downtown, where I park outside the Dollar General.

In Species of Spaces (1974), Georges Perec calls the neighborhood “a familiar space [which] gives rise to an itinerary . . . a pretext for a few limp handshakes.” Wilmerding, PA’s grip has often been firmer than my own. Occasionally crushing, white-knuckled. How many times I’ve been introduced to a “machine hand” who once worked with my grandfather at the Air Brake.

Two young girls enter the Dollar General, singles fanned out. I notice they’re barefooted. Their toes flex against the tile as they do candybar arithmetic. “I think we can get five of this size,” one says. I buy a package of pens and leave.

![]()

I begin at a four-way intersection on the other side of the creek, the westernmost point of Airbrake Avenue (just outside of Wilmerding in Turtle Creek)—a pen clipped to my notepad and tape measure clipped to the waistband of my Levi’s. I’ve decided to measure the avenue’s sidewalk cracks, the ones my father once leapt to spare his mother’s back. Even though she’s gone, her back now parallel and subterranean with her husband’s at St. Michael’s Cemetery, I keep my ear to the ground and listen for her sound as I crouch, measure, and record every breakage in the cement. This is borough forensics. I am closest to the surface across which Wilmerding’s feet glide, and I am picking through all the let-go litter. By the time I arrive at Valley Laundromat (and Donut Shop), a few scant paces from my point of embarkation, I’ve already genuflected six times to measure the sidewalk cracks (SC).

SC #1: 8¼ʺ

SC #2: ¾ʺ

SC #3: 1ʺ

SC #4: 3½ʺ

SC #5: 1ʺ

SC #6: 1ʺ

My methodology is wack. I ignore cracks smaller than 3/8ʺ, am prone to approximation, am not yet sure what to do about the crocodile cracking. Am I to measure each fracture of its concrete webbing? The first step in calculating pavement condition, according to Mahmood et al., is to “determine severity, and the extent of each distress type for a pavement section.” I see the houses to my left shoulder, their paint cracking too, and remember blight can be vertical. Blight is the pall that mistakes our cities for tombs, begging us to look away.

A man balances a laundry basket on his bare shoulder as he opens the trunk of his LeBaron, parked at Pinky’s Billiard Parlor. “It look like you on the chain gang,” he says to me as I kneel to measure a crack just a stride away from his back left tire. “First down?” he asks, extending his arm perpendicular to his body—down “field,” that is: down Airbrake Avenue. Inside Pinky’s, people are watching the second quarter of the Steelers-Niners game.

“First down,” I confirm, recording SC #7: 3¼ʺ and its lengthy tributary, SC #8: 10ʺ. The pavement-distress density can be calculated by dividing distress length (or number of potholes) by section area. “That’s it,” he said. “That’s the way.” He fist pumps before freestyling his limbs through the armholes of a just-laundered Lawrence Timmons jersey.

I amble toward Better Feed, whose windows advertise wild birdseed, pet feed, nursery stock, hanging baskets, and bedding plants. In George Westinghouse’s biography, Henry G. Prout documents the aesthetics of old Wilmerding, the forgotten project of beautification. Many years ago, the Westinghouse Air Brake Company held contests for the best gardens and lawns, making “the little town . . . a focus of taste in a commonplace and even dreary region.” Among the original planned cities in America, Wilmerding was the first true company town. For the earliest decades of his life, my father lived in a “Westing” house contracted for workers of the Air Brake Company, workers like his father and his father’s father.

What happens, though, when the plans are aborted, the planners deceased or dispersed? Weeks ago, Mary Comunale petitioned the Wilmerding Borough Council: “I was here last month about the house next door to me, where grass and weeds are over six inches. Nothing has been done . . . We need some help.” Over the minutes, members discuss the catch basin in Lilac Alley (not working), the curbs in the business district (crumbling), and the water weeds outside of Wilmerding Beverage (need spraying). I imagine Mary Comunale, sitting on her porch, swinging beneath awning’s shade as the grass grows up to her eyes. I imagine her miniaturized by the wilderness, turning pest-like. If only she went inside for the scissors, slipped her thumb knuckle past the brim of the eye ring, snuck into the neighbor’s yard, and sheared.

![]()

When I was very young, my uncle explained that the men of my family—my father, his father, my father’s mother’s father, five “great” uncles, six once-removed cousins, and even the women during WWII—had collectively contributed over three million hours of labor to the Westinghouse Air Brake Company. “That’s a minimum,” he told me. Once released at shift’s end, their heels clobbered the cement sidewalks, homebound.

For weeks, I have been phoning Human Resources at Westinghouse Air Brake Technologies Corporation (the modern incarnation of the Air Brake), but nobody returns my calls. I leave messages, plead: “I just want to see the inside of the place. It’s very important to me.”

There’s an apocryphal story from the 1920s in which my great-grandfather, Nick, applied for a job at the Air Brake. The manager allegedly became uninterested, even dismissive when Nick shared his Italian surname (Lenbratto). Nick was crestfallen; before leaving the factory, though, he glimpsed the roster, looking for a name near to his own. His curiosity evolved into deceit. Within a week, Nick was an employee of the Westinghouse Air Brake Company; he had returned to the factory and fibbed about his surname to a different shift manager. This is how we became Lenharts.

“Hello, it’s Lawrence again. Lenhart. Will somebody please look into my previous requests?” Don’t you understand? The Air Brake named me. I am a rightful pilgrim. I imagine my voice mails being played ad nauseam in the modern break room, the undersized work-force (7.5 percent of what it once was) laughing at my vibrations; in a postnostalgic town, my pleas become mawkish prattle.

![]()

Long before George Westinghouse invented the air-compressed brake (before 1868), train cars freighted through the Lower Turtle Creek Valley along the Pennsylvania Railroad to or from Pittsburgh, stopping unsteadily, jolting as the engineer quit the engine and the brakemen turned handwheels, tautening chains that forced the brake shoes against the locomotive’s headlong wheels. Generally, the cars streamed through the valley toward the city. If the flag was raised at the request station, though, the train’s whistle squealed as it approached a small timber dock where coal carts from the Oak Hill Mine waited to be backed onto a railroad car. The stop was known as the Joanna Wilmerding Station (after the mine owner’s daughter). In time, it was shortened to Wilmerding, her name broadcast over the valley.

When the state denied Wilmerding new signs for its centennial gala in 1990, boosters financed a small-scale Hollywood-style sign constructed on the borough’s hillside. This act of reactionary boosterism glamorized blue-collar W-I-L-M-E-R-D-I-N-G. After dinner each night—my tongue eroding the bits of Grandma’s pork chop sticking between my teeth—we’d drive home to North Versailles, and I’d practice the borough out loud. It became the first three-syllable word I knew how to spell.

![]()

It starts to feel asinine, collecting these measurements (SC #49 through SC #56 totaling 11’, 4½ʺ). One doesn’t have to look this hard to detect the blight—the discolored awnings with cracked numbers, leaning fences, for lease/for sale signs, shuttered storefronts, and shed letters off the Sub Alpine Society marquee. Still, though, I’m striving for something more quantitative. I need a number to calm my father’s speculative woe. Because it’s Sunday—the few in-business businesses closed (all the welders, mechanics, and contractors saddled on barstools or nestled on couches somewhere else in Allegheny County, watching the Steelers besting the Niners (the coal rush versus the gold rush))—the streets are mostly deserted.

Eventually, I do see one child pushing a doll carriage on the sidewalk. Closer, I realize she’s a teenager. She grips an actual stroller, its canopy closed. She swerves into the street as a courtesy. The shabby stroller swoops off the curb, scraping over a square of hot patch. The baby moans, and I apologize, though I’m not sure why.

Scores of us were born in this borough, and some of us (not me) raised by it. Hear the polyrhythmic sobbing of every generation buzzing from the carriage as if through a boom box. I feel guilty for hijacking this swath of sidewalk. I am no Wilmerdinger. Is that even the right demonym? I’ve likely been misusing it for years.

If I add up these cracks, I’ll have summed up the parameters of neglect. I’ll know exactly how our family’s flight contributed to the blight surrounding me. Sometimes by taking one dramatic step “toward,” I give myself permission to run states away. If first we packed our boxes and left for the suburbs, I’m now returning for the morsels in the cabinets, the cigarette burns on the rug, the moss in the grouting. With the last crumb and char and clump dropped in my pocket, there will be no reason to come back. I am finding new ways, more final ways, to vacate this borough. If I could just, as Georges Perec has claimed to do, manage to “inhabit my sheet of paper . . . invest it . . . travel across it,” then I will never have to go back to Wilmerding again. It will all be here in the lignin, a static portrait that gets no worse (no better). Hurry, before it’s full-on terra nullius. Before it redeems its lottery ticket.

![]()

First, the Elvis impersonator came to the Castle on select weekends.

And for every child . . . stands a castle tall and proud . . . the warm wind crawls through the castle walls.

Next, a registered paranormal investigator was hired to certify that the Castle was haunted (thus began the dubious business of Wilmerding ghost tours). Finally, to pay the bills, the offices were leased to a funeral directors’ association. These harbingers of borrowed time—the impersonator, the investigator, and the director, all coconspirators in the art of the uncanny—were predictive of the Castle’s mortal future.

In its next incarnation, the Castle may be bought and converted into a boutique hotel by the Priory Hospitality Group (PHG). In an article in The Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, former Wilmerding mayor Geraldine Homitz praised PHG President and CEO John Graf: “With everything that people have . . . tried here, nobody else has the imagination to do what he’s doing.” In an article in The Wall Street Journal, Graf “acknowledged that Wilmerding’s charms are faded but said the Castle, if renovated, ‘creates its own destination.’” Offering billiards, croquet, and lawn bowling, the Castle could be a venue for a “romantic weekend” in Wilmerding.

I’ve known romantic to be the verbiage of gentrification. Romantic: not just a word, but a lifestyle too. Think settlement movement.

Now, the bellhop’s tears keep flowin’

and the desk clerk’s dressed in black.

I am wary of the nostalgia industry; its guise of restoration is a blueprint for social stratification.

Well, they’ve been so long on Lonely Street . . .

they’ll never, ever look back . . .

What utility is there in a boutique Wilmerding? What futility?

Just take a walk down Lonely Street to the Heartbreak Hotel.

![]()

It’s halftime on the avenue, the Steelers leading 21–3. Three boys play tackle football between hedgerows. Their field is less than ten yards long. They notice me, and the boy with the hard plastic ball yells, “Catch!” I catch the wobbling red football and hesitate before choosing my receiver. Two of the boys clamber in mutual defense. The third, runty looking, a shaved head and small left eye, presumes I won’t be passing it to him. When I do, this jilted playmate juggles the catch before dropping it.

“What are you measuring?” the runt asks, noticing the conspicuous tape measure on my hip.

“His dick,” his friend says before I can answer. I fix my face into a compulsory frown.

The runt throws the ball to me, an underhand shovel pass. He bee-lines on a route, arriving at a statue of the Virgin Mary. I fling the ball, and it’s another failed reception.

“Who lives here?” I ask.

They exchange looks. No one seems to know. The ball is thrown back to me. They are from Middle Avenue, also known as the Flats, but they come down to Airbrake Avenue to play football. They explain this to me as they juke indeterminately. For a moment, I forget I have the ball. It’s as if they have induced hysteria, the way they dash and jitter their fingers.

“They’ve got all the yards down here,” one boy says, unable to conceal his envy.

“What are you measuring?” the runt asks again. “Really.” “I’m measuring the cracks in the sidewalk,” I say.

“What for?”

“Because he’s a crack dealer,” the jokester jokes again.

Ignoring him, I explain to the runt, “I’m on official borough business.” It’s unclear if he knows I’m bluffing. “I’m conducting a manual survey of the pavement. Have a good day, guys.” I roll the ball from the sidewalk to their feet, and continue walking.

“On a Sunday?” the jokester yells at my back, sounding doubtful that anything “official” can happen on a Sunday. “Bull. He’s measuring his dick with that tape.”

![]()

With 32 patents to his name, perhaps Westinghouse’s most significant invention was the weekend. He was the first American industrialist to inaugurate the weekend: imagine blue-collar workers crossing the Air Brake’s viaduct midday on Saturday afternoons in 1869, freed from their labor to picnic with their families. Among them, my great-grandfather: released!

Two generations later, my father and his brother used to teeter on the rail of the viaduct, on the precipice of a new weekend. There, they waited for their father. “First, you’d see these young guys sprint out of there like they were just freed from jail,” my father says. “Then, the next group, a little older, would walk out naturally. That’s the group Dad was in. But if you stuck around, about five minutes later, you’d see the guys with a limp. And finally, the last ones: they moved like they had just barely made it out of there alive. That explained the whole life cycle to me.”

The valley managed to maintain its attitudes toward workers’ rights long after Westinghouse passed; nearly a century after the Air Brake’s first weekend, The Vogues (of Turtle Creek) insisted through the blue-eyed soul of “Five O’Clock World”: “. . . when the whistle blows, no one owns a piece of my time.”

![]()

If the Castle has a resident ghost, let it be my paternal great-grandfather, Nick, the Italian who swapped his name for a wage.

If there’s a second ghost, let it be my father’s maternal great-grandfather, Patrick, little Irish pistol who pushed the scrap cart around the factory, scavenging the metal chippings from the floor into a bucket, wearing a skullcap with no beak, collecting union dues, but running numbers too, indebting men whose wives would soon come to collect checks to buy groceries at the A&P, checks that always weighed less than they should.

And if there’s a third, making up a spectral triumvirate, let it be George himself, preparing now to topple wickets on the lawn because the people of this town play football, not croquet.

![]()

Turtle Creek empties into the Monongahela River, eddying toward Braddock, four miles west of Wilmerding. In a recent commercial depiction of Braddock, a silver train passes a campfire as a blue-eyed dog and his scruffy owner invoke urban pioneerism.

Levi’s Braddock is thinly veiled poverty porn: see the decommissioned bridge and plywood windows, the abandoned car engorged by knotty vine, busted auditorium seats, and scaffolding. In Monthly Review, Jim Straub and Bret Liebendorfer write, “As far as scenic ruins go, the Pittsburgh metropolitan area sets a high standard. The natural beauty of the Monongahela Valley and the built legacy of deindustrialization make gorgeous scenery of blue-collar defeat.”

In the commercial, a young narrator suggests, “Maybe the world breaks on purpose so we can have work to do.” By framing deindustrialization as an entirely natural process, like a controlled burn in wildfire ecology, the implicit message is that blight is an acceptable form of ruination. The active voice (“world breaks”) forces the consumer to retract her pointed finger (“was broken”). Maybe it’s Levi Strauss & Co.’s way of making sense of the devastating economic upheaval it caused its stalwart workers following the successive closure of all its American factories.

“People think there aren’t frontiers anymore,” the girl narrator says. “They can’t see how frontiers are all around us.” The commercial ends with the camera accelerating down a quotidian street similar to Airbrake Avenue. Then, the camera takes flight—the skyward lens is Icarian—and an imperative is stamped on the screen: “GO FORTH.”

![]()

If I was to make a commercial for the bygone borough, my Wilmerding, I might focus on the variant cracks—alligator cracking, block cracking, edge cracking, longitudinal cracking, transverse cracking, slippage cracking, bleeding, bumps and sags, corrugations, depressions, joint reflections, patching, potholes, rutting, swelling, weathering, and raveling—and I’d soundtrack it to pithy poetry, maybe Leonard Cohen singing “Anthem”:

Forget your perfect offering.

There is a crack in everything.

That’s how the light gets in.

![]()

In a 1904 article in The Wilmerding News, a visitor to the borough pointed out that “every foot of street will have been paved [with fire brick] in the near future. All streets are sewered . . . and lighted by arc lamps.” The visitor also mentioned Wilmerding had been improved by its “fine paved sidewalks.” Nearly a century later, a door-to-door contractor walked the avenue, offering exclusive prices for concrete slabs. Wilmerding needed new sidewalks again, and the residents were expected to pay out-of-pocket. While some residents refused to pay for the maintenance of a public path, my grandparents—wanting to protect their home’s curb appeal—added their names to the list. After the concrete was poured, my grandmother offered the $400 to the contractor. He refused her payment. In a karmic twist, the borough footed the bill only for those who were initially agreeable, those who bought in to the project of beautification.

Just a few years after these new sidewalks had dried, I pedaled my tricycle from its parking spot next to the Chevy Caprice in my grandfather’s garage. I’d sail the rectangular sidewalk while my grandparents sat on the porch swing. Each time I reappeared—it took a minute or so per circuit—they’d call out a number, tallying my laps. Sometimes, when the neighbors were outside, they’d shout the number too. In Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation over Public Space, Jane Jacobs calls sidewalks ‘‘‘the main public places of the city’ and ‘its most vital organs’ . . . sites of socialization and pleasure . . . [which keep] neighborhoods safe and controlled.”

I measure 31 sidewalk cracks, SCs #90 through #121 (21ʹ, 4ʺ), on this main section, the old block where my grandparents lived and died. I used to mow my grandparents’ lawn. As the yards were small, I would sometimes push the mower over the neighbors’ grass as well—it was just easier that way—but my grandmother insisted I discontinue this practice. “Everybody has to keep up their own,” she explained. The sidewalk, though, public and parochial: to whom does it belong?

To the east of my late grandparents’ house, two octogenarian sisters live next door to one another. When a sidewalk crack appeared between their houses this past year, straddling their property line, the two argued over who was responsible for its repair. I stand on the property line now, the wary impasse. Sociologist Lyn H. Lofland has called sidewalks “simultaneously public and parochial—open to all and yet a space over which a group feels ownership.” I peek for longer than I should, squinting at the crack in question, offering silent unsolicited arbitration.

![]()

After my grandparents’ block, the measuring feels more perfunctory. At the beer distributor, Wilmerding Beverage (once a soda manufacturer that made the signature pop, Mission Orange), I see the water weeds that were mentioned in the council minutes. I yank a few so that I can properly measure the cracks from which they are sprouting—six alligator cracks, SC #158 through #163 (7¼ʺ).

When I check my phone, I see three missed calls from my parents. Originally from Wilmerding (1947), my father has moved farther and farther eastward—to the suburbs (1970s) and then to the newer suburbs (1990s). Before I left for his hometown this morning, he warned me that it’s “gotten pretty bad. All the windows are boarded. People have just given up.”

![]()

In 1904, it took 90 minutes to get from the Turtle Creek Valley to Pittsburgh on the trolley line. Now, one can reach the city limits in less than 20 minutes. Industrial boroughs like Wilmerding are necessarily dependent on the industrial centers nearest to them. From The Wilmerding News (1904): “Reduced orders for air brakes” or any specialty product will affect the company, and “naturally when business is slack, there is slack in the town, also.”

In President Barack Obama’s 2009 statement ahead of the G-20 Summit in Pittsburgh, he lauded the city for “[transforming] itself from the city of steel to a center for high-tech innovation—including green technology, education and training, and research and development . . . a beautiful backdrop and a powerful example.” However, the city’s transformation further abandons the outer boroughs whose works exclusively served the once hyperindustrial city. In this case, transformation looks a lot like desertion.

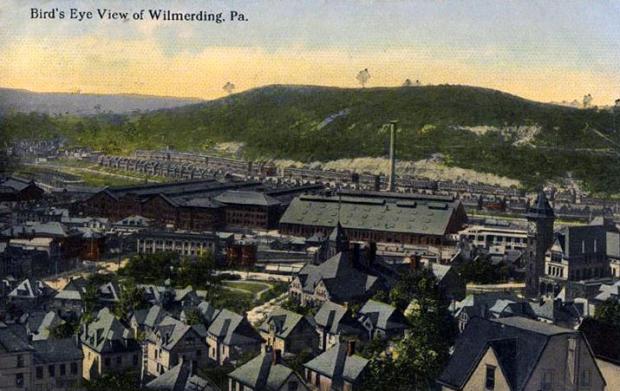

One of America’s first company towns (seen here in the early 1900s), Wilmerding was deindustrialized in the 1980s.

One of America’s first company towns (seen here in the early 1900s), Wilmerding was deindustrialized in the 1980s.

After the day’s long walk, 680 sidewalk cracks (collectively about a quarter of a mile in length), I park outside the house in the Flats where my father was raised, before his parents could afford the two-bedroom home on Airbrake Avenue. When I was young, I referred to it as the Westing house. It’s late evening as I lower the windows and recline the car seat. My dad used to petition his parents to be allowed to sleep on the porch in the summers. In his pajamas, he’d settle into those balmy nights, rubbing his toes together in sync with the stridulating crickets.

I listen for them now, but only hear subwoofer. On that porch, a red light bulb glows. I drift to sleep, ignoring calls from my parents. They’re worried that I haven’t come home yet. How to explain I am home? They’re the ones who have left.

At 1:04 am, I wake to laughter. I peek over the passenger window’s ledge to see a young black couple climbing the stairs to the porch. Their laughter is so genuine, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: I start chuckling myself. At what? I recall the ugly line in The Wilmerding News: “Wilmerding is fortunate in having few foreigners and negroes of a low type among its population.” I hear this century-old index still ready on the tips of tongues as the eminently affordable Wilmerding is repopulated. It’s hard to point the finger at the borough’s real problems because they’re in hiding: behold the absentee landlords of Greater Pittsburgh. No town breaks on purpose, just as no town gets fixed by accident.

As an adult, it seems unfair that I have to ask permission to sleep outside the old row house. It’s almost 2 am. when I finally call home. “If that castle hotel was open,” Dad says, “you could check yourself in.”

![]()

John Graf will buy the Castle eight months later for $100,000 at a sheriff’s sale. This is less than it cost to heat the Castle annually in its previous incarnation as a banquet hall. At 55,000 square feet, Graf’s investment will be $1.80 per square foot, or as far as commercial spaces go: only 8 percent of the national average. My father will call it the deal of the century. My godfather, “a steal.” It’s hard for me to really discern what is being stolen. I’ll remember the last contents on the lawn, those three auditorium chairs displayed in what was once a backward-looking museum, and I’ll wonder if my father once sat in the middle one, flanked by his two buddies from highschool, Artie and Charlie. If these seats are permanently extracted from the borough, then where will the three young football players from Middle Avenue sit in a few years’ time? Geraldine Homitz will say, in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, that the “the whole town is happy” about Graf’s purchase. The businessman plans to spend up to $9 million (jackpot!) in renovations, and it is a certainty that the spirit of Westinghouse will be invoked when the ribbon is finally cut with oversized ceremonial scissors next year.

![]()

In Pittsburgh’s Schenley Park, Daniel Chester French (sculptor of the Lincoln Memorial) created a monument to George Westinghouse. A schoolboy, “The Spirit of American Youth,” lingers before panels depicting Westinghouse’s accomplishments. Nostalgia has the facade of a wheelhouse, but the momentum of a runaway. Months later, as we’re driving through the park, I’ll ask my mom to stop at the memorial. Barricaded by chain-link and orange safety fence, the memorial is green-tarped, the ground around it dug up like an excavation site. I climb an oak tree to see past the oversized signage laying out plans for the “Westinghouse Memorial Restoration Project.”

![]()

When I wake at 6 am, the red light bulb is still on. I hear a baby sobbing from inside. As I study the house, where my uncle (Baby Johnny) slept in a drawer next to my father’s bed, always wailing, dying from hydrocephalus, I realize that I’ve only entered this house through narratives. It’s a dangerous habit, constructing monuments only of the past.

This is my moratorium on the story of this house. What’s the point in imagining it as it used to be? Now I think I’d like to see it as it is. I read a book about Nikola Tesla while waiting for the red bulb to go off. In 1893, Westinghouse (with the help of Tesla) underbid Edison’s General Electric Company for the honor of illuminating the World’s Columbian Exposition. Nearly 100,000 incandescent lamps were installed alongside neoclassical architecture and Frederick Law Olmsted’s palatial landscaping. This world’s fair was the starting line of the City Beautiful movement. From a distance, though, those in Chicago’s boarding houses thought the city was on fire.

It’s too reckless to worry from afar. Instead, dispatch the espirit de corps to the avenues of these boroughs whose cracks need tallying. Assume the mantle of the postnostalgic flaneur. Become an honorary Wilmerdinger. Wade through the streets. Beg for a signal. A summons. Wait for someone to finger the switch.

At some point, the light goes off. My vigil is over. I leave my car parked, tires kissing the sidewalk, and I climb the stairs to the porch as if just heading home. I hear the righteous sound of my knuckles knocking on The Door. Several hundred feet above Airbrake Avenue, above Turtle Creek and the great factory, I’ve never before enjoyed this view of the valley. I’m waiting in Wilmerding to be let in. The man opens the door and nods before saying hello to me. We are strangers, verging on a homecoming. In that moment, with his feet inside and mine out, he is home and I am nearly so. I make my case, and he opens the door further. The Westing house swallows me home.

* * * *

NOTE. Quotes in this essay about sidewalks come from Jane Jacobs and Lyn H. Lofland’s writing on the subject in Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Renia Ehrenfeucht’s Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation over Public Space (MIT Press, 2009). Some quotations about Wilmerding come from an article, “The Ideal Home Town,” found in the September 2, 1904, edition of The Wilmerding News, as accessed from the digital collections of the Library of Congress. This essay was developed as part of the Writing Pittsburgh project through the Creative Nonfiction Foundation.

__________________________________

This essay originally appeared in Conjunctions: 68, under the title “My Wilmerding: Wheelhouse or Runaway.”

Lawrence Lenhart

Lawrence Lenhart is the author of the essay collection The Well-Stocked and Gilded Cage (Outpost19) and an editor at DIAGRAM.