At the red gate, the massage therapist wrote in the first message. After no answer: I think this is you?

In bed, surrounded by the morning’s work—corsages of crumpled tissue, coconut crumbs—the phone chimed again. Quit it, Layla hissed, eyeing the bassinet.

It was a pill-shaped piece of furniture. The base was mahogany, and the sides were bone mesh. Its thin legs were bent, scalene rabbit-ear antennas. The design sedately nodded toward mid-century, a “smart” sleeper: an algorithm, a subaudible motor, a sensor that would discern baby cries from background noise. Layla kept the bassinet unplugged.

It was a season of fires. They radiated out from Los Angeles, blasting through the Hills, and last night one had overtaken the Catholic college where Layla taught. Her students, girls shawled in blankets, hugging their backpacks marsupially, were evacuated by ambulance and Mercedes van. She was their chic-aunt professor, they trusted her with their truth, and they were flooding the class discussion board with videos of the 405 sky bleeding out, streaky, dirt-red apocalypse.

Here ?? a new message read.

She took a small brown envelope from under the pillow. Yesterday it had contained six raw CBD macarons; today there was one. But classes were canceled. The universe of California was giving her a pass, pardoning her 660 stoner calories. She put the macaron in her mouth, crumpling the envelope, bonbonnière of the cannabis age. She’d used the word bonbon in a lecture, once, and been met with blankness. Bon, as in good, she’d said, like . . . that good-good.

Layla wobbled over to the bassinet. She touched the mesh and straightened the swaddle spread out on the thin mattress, a pouch of stretchy fabric printed with madly smiling daisies. Her neighbor’s bird often caused the sensor to misfire, triggering a broken, brutal rocking.

*

Outside, the courtyard was hazed in opalescent light. Under the fermented tang of figs, sour red queens that fell from the mammoth Moreton Bay, the air stunk of smoke. Thirty miles away last week, fifteen this morning. The closer the fires, the less they bothered her.

She squinted against the high eastern sun. Behind the fence, a woman in compression tights and a top with a mandarin collar waved.

“I heard your shoes, mama,” the woman said, grinning at Layla’s velveteen mules. The woman dropped her phone into a tote, where a bolster stuck up like an enormous baguette.

She introduced herself as Beri, short for Bernice, Beri Yawn. “How’s the morning going?” Beri asked, glancing around the courtyard. An armless Venus, the sooty bin of a grill. A glitter of hummingbirds above the hedges, floating birthstones, too light to leave a shadow.

Layla exhaled.

“The world is crazy right now,” Beri said. “Good for you for making time for yourself with all this. How’s the baby doing?” Layla kinked an eyebrow behind a pair of Prada sunglasses from a few seasons back, when she and the world had had more levity, when fashion could still be arch. If now were then, the frames would be perfect: chunky, jagged flames. “I’m this way.”

She decided to say nothing as much as possible. If she was tempted to talk, she’d eat the camellia oil from her lipstick. She had gotten dressed today, every day this week. Short black tulip skirt, gold Calyce clip-ons, glamorous house shoes. She put on makeup. She was a woman who valued self-maintenance, who believed tiny luxuries might save her. That woman had booked a treatment, a postpartum womb massage. Beneath her mules, the figs flattened into teardrops, smashed open and purple, exposing their withered seeds.

*

Relax, Beri insisted, she’d call if she needed anything, but Layla hovered over the bassinet, half-monitoring the preparations.

Beri was sporty, color-blocked—purple-tipped ponytail, dense white polish on her toes—and she moved swiftly. She turned on a portable speaker, set a jar candle on the nightstand, and out of the bag came the bolster, a folded white sheet, a deep blue towel.

“Do you have a lighter?” Beri asked, testing a pillow, one of the firm ones that Layla had splurged on for Dom’s (canceled) visit. “I used my last match.”

The air stunk of smoke. Thirty miles away last week, fifteen this morning. The closer the fires, the less they bothered her.

In the kitchen, Layla opened a drawer. She gazed out the window at her neighbor’s tile-roofed mansion, the secluded in-law casita behind the patio sprouting with a family of green garden umbrellas. Her apartment was small. Not awful for Los Angeles. Fine for her and a newborn. A one-year-old. Even a toddler, maybe. And the views, bubblegum jasmine and bamboo her neighbor nurtured. He was a beautiful man with a lovely, hopscotching accent, a rich Cuban teddy bear with fabulous shoes. Plus, the bird. Layla had never seen the bird, but she imagined its celadon feathers, its canny eye, bloodshot from smoke, sizing her up from its invisible perch. It watched her test the lighter, squawking its catcall: wee woooo.

“Did I mention how amazing you look?” Beri said when Layla came back. “Honestly, I couldn’t even tell that you just had a baby. That’s hard work, mama!”

Layla frowned. “I used to be a gymnast. And I did hot yoga—”

“My mother made me do gymnastics,” Beri said, smoothing a wooly blanket over the sheet. “Even though I was absolutely terrible at it and basically born with the wrong body, according to my Chinese mother. By the time I was nine, I was, say, five-one. One hundred and twelve pounds? Or maybe one hundred and five? Not huge, but the other girls were these seventy-pounds sprites. Um, no. The whole sport is one big anorexia incinerator.”

“Incubator?” Layla said.

She could never imagine imposing anything like that on her daughter, Beri said. James, she told Layla, will be one next week, and she’s such a tomboy, so rough and tumble even though she was born at twenty-eight weeks and spent her first three months in the NICU.

“With a needle in her skull,” Beri said, lighting the candle. French vanilla bloomed. “My partner and I had to literally advocate for her to be fed. The nurses in the NICU were withholding. How messed up is that?”

Nick-U, Nick-U. Layla had never heard the word spoken, had only read it in tiny font truckled by video ads on her phone in this bed, and it hung before her like a hologram, a door to another room. Edibles messed her up. She was queasy. The macaron was still in her throat, a clot of oily, salty coconut. She bit her tongue and felt herself float off, like a syllable.

“So,” she heard Beri ask. “Where’s the little nugget?”

*

All choices are bad choices in love, Layla would say, bad romance, she said in her Deviant Women classroom, blackboards iced over with sliding dry erase panels, plagiarizing Proust and Lady Gaga, both ancient history to eighteen-year-old girls.

The trope of the chance meeting.

Love at first sight?

Think about it.

She would stare off out the window, stretching a minute into eternity, gazing at the confused blue horizon, where the Pacific Ocean seeped into the sky. When there were choices in a relationship, she said, they could only be bad because it meant the socialized mind, the rationale mind, your mind governed by fear and logic and buy-buy-buy, white-picket values, your mind had won at the expense of your heart, that boiling hopeful organ. The girls blinked at her skinny thighs, mottled skin peeking through the fishnets, each gap in the stockings a new question: Do you have a boyfriend? Are you married? Do you have kids? They were most curious at the start of the semester, when she told them they could ask her anything.

-Thirty-nine. Yes. Thank you. I work hard.

-Handstands.

-A chile relleno burrito. From La Azteca—.

-Boot shopping with Madonna.

She had met Dom over Labor Day weekend, two weeks into the term. Her students knew nothing of Chicago. She’d forgotten to pack underwear and bought herself a seven-pack from the Girls department at Target, Days of the Week. When she’d swiped right wearing Tuesday, cotton-candy pink, dizzy-eyed unicorns, she was on Roosevelt Road, mouth frozen and red from Morello cherry ice, sun-blissed and kissing the arm of an impossible bookish king of the Gold Coast, staggering back to his soaking tub, his bed, between fucks five and six getting herself the wettest she’d be all the livelong weekend ogling his bookshelf. He had a degree from U of C, translated Italian folktales and poetry, mainly the hard labors of Pavese for fun—bahaha. He collected dictionaries. She took down two and opened them on his desk. She had one hand over cloaca and the other on keime when he came so hard the condom broke.

*

She floated back. Curtains pulled shut. Bed covered by white sheet. Vanilla candle burning.

All choices are bad choices in love, Layla would say, bad romance, she said in her Deviant Women classroom, blackboards iced over with sliding dry erase panels, plagiarizing Proust and Lady Gaga, both ancient history to eighteen-year-old girls.

“Ready when you are,” Beri said. It was a deep, athletic voice, the voice of a woman with strong hands. “Keep your underwear on, bra optional—it’s nice if you’re leaking.”

Layla stepped out of her mules and shortened by an inch. She unclasped her skirt. She left on the ratty lavender sports bra she wore for Bikram.

“Careful getting on the bed,” Beri said. “Are you sore?”

Awkwardly, as though horizontally jumping a hurdle, she laid herself down. Did Beri notice her hammerhead hip bones? Once Dom had come between them, that dip below her navel he called la fossa. Touchdown! she’d crowed, so high off gummis and ardor that everything she said seemed brilliant, nine times in a row brilliant, how do you radio silence someone worth fucking nine times in twenty-seven hours? An hour or five bags of macarons, four tubes of Melrose lipstick, one-third a haircut, one month at her yoga studio, one-seventh her rent, half a flight to Chicago; one one-hundredth the cost of freezing her eggs, round two.

“I’m going to put on the eye pillow now,” Beri said. “And a towel to protect your hair from the oil.”

She gathered Layla’s hair and turbaned the towel. The eye pillow was snug, eucalyptus-scented silk filled with tiny beads. “Deep breath in,” Beri said. Her palms pressed on Layla’s shoulders. “And out.” There was a heavy touch on the ball of her left shoulder. A pause. For a moment, she only heard the thrum of the ceiling fan, its dust-furred blades churning smog and spindly-legged mosquitos that squeezed in through the gaping screens. Then, over the speaker, a muted chant and an echoing bell. The pump of lotion. Beri kneaded, working the moist slop over her sinuous bicep. Down, tracing around her elbow, the knobby point, the inside, a pond of flesh marked with good veins.

One by one, Beri tugged her fingers. The pinky and thumb knuckles cracked.

“Relax,” Beri whispered. She picked up Layla’s arm and shook it like a useless tube. “I know it’s hard, mama. Relax.”

She covered her left arm with the wooly blanket and changed the music. Behind the eye pillow, Layla blinked. Wee wooo. Outside, a woman yelled, Tamales! Layla pictured her north of the courtyard, far from the Cuban teddy bear’s dollhouse of umbrellas, pushing a shopping cart filled with tamales all papoosed on a bed of newspaper.

That’s what people said, and Layla had never seen it, but she believed it. She was trying.

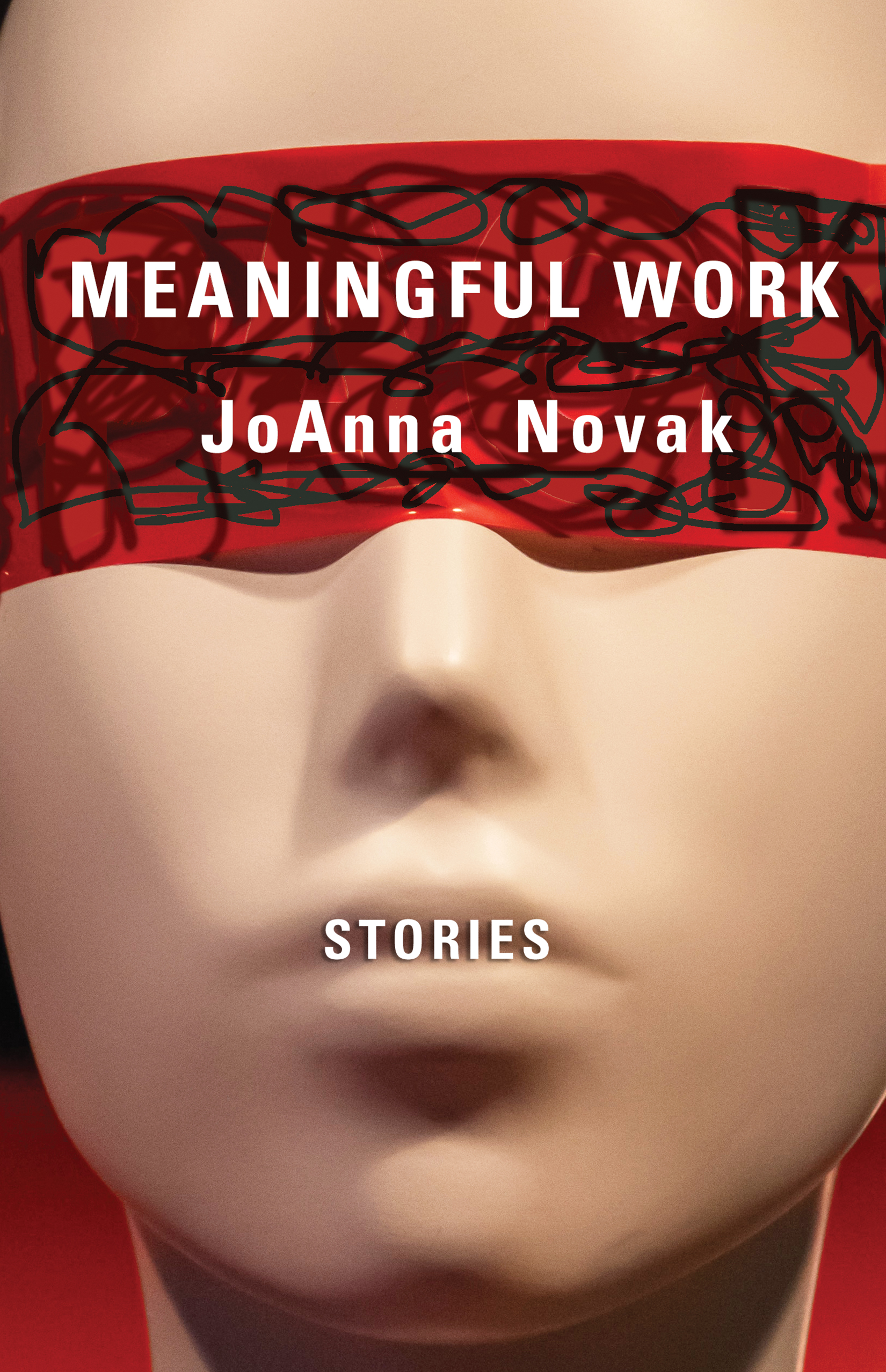

__________________________________

Excerpted from Meaningful Work by JoAnna Novak. Reprinted by permission of FC2/The University of Alabama Press.