McKenzie Wark Writes a Letter to Her Younger Self

On Love and Money, Sex and Death in Australia

When Little Richard came to our hometown, he left us some- thing like a gift. He came to Newcastle on his Australian tour, in 1957, four years before you were born. He was this churning, surging flame, icon of a new thing called rock and roll. Then his life took a turn while crossing the waters of our harbor.

Your life will take some turns too. I’m writing this to you from your own future, or a possible one at least. A letter to a young poet, where the young poet is me, forty years ago, not quite twenty years old. A letter that’s cover for a medley of others, addressed to others, about love and money, sex and death.

You—what do I even remember of you? Our past selves are probably extensively edited editions. Let me see what I can piece together.

I’ll try not to advise, as you won’t take advice. You never seek it. You are incapable of being mentored. A lot of people will help you. Perhaps they see the wound that keeps you from asking. They’ll help you in spite of your indifference, even antagonism, to care. To accepting love.

You don’t think about this much, but I have to insist: we lost our mother young, and we never much liked our distant, irritable father. The two frontline adults meant to be there for us, keep the world at bay, weren’t. That made us distrustful, detached, dissociated. Look that last one up, it explains a lot. Like in Kimba the White Lion, that TV show you loved when you were little, you feel alone in the world.

It is obvious to you already that a world that relies on little isolated family units subject to the whims of the market and disease is a bad idea. You want a better world. The past hurt you, so you move on, and want the world to move on. You’ve not yet learned to live in the present, so you live in the nothingness of a permanent not-yet.

Your family tended their own wounds after your mother died. As the youngest, you couldn’t see that. You needed them all to not fall apart so they could hold you together. They did their best, but you needed more than that, so you started looking for ways to get attention.

Big brother smoked. You found an old cigarette tin, rolled pencil stubs in paper, and made them into a fake brand. You called them “Snazzies: the cigarette for the fancy smoker.” You made it into a bit, and everyone thought it was cute. Bigger kids still pushed you up against a wall and took things from you, but sometimes they too could be charmed.

You feel vulnerable, fragile, too open to the randomness of the world. You’ve already got good at monitoring the perimeter, scanning for danger, checking you have all your kit. You’ve just moved to Sydney from your hometown, and those skills come in handy.

Don’t think I’ve forgotten that time you came back to Newcastle and slept on a former schoolmate’s couch rather than go visit your father. Don’t think I’ve forgotten how, hard up for cash, you sold a matchbox of weed to someone else you thought you’d left behind. He complained it wasn’t much pot for five bucks. You said take it or leave it. He took it, but got his bigger mates to find you, sit you in a car and make you roll the regulation five joints out of it under threat of consequences. And you did. Grace under pressure. And all forgotten. Mates again, smoking together in the car. Fuck those losers. You’re not living in their world again, ever.

Little Richard left Macon, Georgia, for a life on the road, performing. He was the son of a preacher who also owned a nightclub. He grew up religious. What he loved most was the ecstatic, stirring energy of church. The intensity of it, that raving joy and surrender in a racist world of pain, poverty, and police. Not like your upbringing at all, although there might be one thing you have in common.

Now back home for another brief visit in Newcastle, back to that steel, coal and port town with its belching smoke and bending beaches. You were right to fuck off immediately after high school. You need a city big enough to let you get weird. You want your life to be Wildean and singular. Mate, you have no idea.

You won’t listen, but I want to talk to you anyway. Need to, perhaps. Need to make contact in some way with that skinny teenage boy. Boy? Man? That’s the rub. Or part of it. You take refuge in androgyny. That picture of Patti Smith on the cover of Horses is your icon. Your hair long, wearing girls’ jeans, girls’ boots. With your slight frame, you’re often mistaken for a girl, and you like it. Whatever those situations point toward, you’re avoiding. Diverting elsewhere with ambitions, politics, writing, some less happy pursuits.

The thing about diversions is that you can never see what’s coming up around the turn.

The diversions will go on a long time. Probably too long. What if you stopped diverting yourself? Or rather, diverted yourself differently? Imagine there’s streams of parallel time- lines, alternate ones, in which you come out as trans at forty, or thirty, or—right now. In some of those timelines, I’m not here in your future to be writing you. In this one, we kept ourselves safe, biding our time till we could come out and remain alive. Little Richard had to get out, so he invented rock and roll.

You want your life to be Wildean and singular. Mate, you have no idea.

The driving beat, the thriving bass, the ecstatic merge. A church- like joy without sacrifice. He performed in drag sometimes, as Princess Lavonne. He—or she—was so different to you but in this maybe a little bit the same. Like you, she loved women whom she wanted to be. She was a girl, and maybe on some level knew it. The only way out was a detour into rock and roll, her art.

You already suspect it—your poetry is bad. Give it up. You’re a prose writer. You’re just too lazy to fill the whole page. You read mainly prose anyway, a lot of it, from your late mother’s library. Lots of cheap Penguin paperbacks of modernist master- pieces. You read moderns to become modern. A whole social democratic education across the yellowing, flaking pages, as if you were in a race to read them before the acid eats the paper. You have access to a charge account at Ell’s bookstore, although sometimes you steal from it anyway, but that’s another story. Science fiction holds your attention when it creates that modern feeling of estrangement from what the reader expects. Much of what you read is bad, but there’s something about reading your way out of this world into another that fills a need.

School was mostly a bore, so you read on your own. Your other source of books, and more, is the local branch of the Communist Party of Australia. The comrades: our marvelous mentors. I still know how to run efficient meetings. Your communism, like more things than you care to know, is more felt than thought. About your mother’s suffering, you could do nothing; about the suffering of labor, that need not be as inevitable as death.

Little Richard was on tour in Australia when the Soviet satellite Sputnik arced bright overhead. An aluminum orb, trailing techno beeps on shortwave radio. That read like an omen, a portent. It was calling. Something had to be sacrificed in a cold world war whose looming strife seemed of biblical proportions. And that offering would be made, by Little Richard, right there in the town where you were born.

In the district party office hung two portraits, Marx flanked by Lenin, strung on two of three nails. On the third, bare, once hung Stalin. Opposite: a vivid poster of comrade Angela Davis. Like in a chapel, she is in the place of the mother, facing off against the father, son, and holy ghost. One had come down from his nail already.

When Soviet tanks churned into Czechoslovakia in 1968, the party split, as elsewhere, into tank and anti-tank factions. On this rare occasion, the anti-tankies, those who denounced the Russians for invading another socialist state, prevailed. The party became a mix of old left and new left, obliged to get along by the rules of democratic centralism.

The comrades remained in solidarity with the revolution even though they knew, in their gut, that we are a defeated people, a lost cause. Yet at least they refused to concede, to acquiesce. Which was maybe why it was the comrades alone whom you accepted as elders. And why I still hold them in my heart, still write to pass along their endless struggle to come.

When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the local party elders entrusted you to lead the discussion at the branch meeting. You affirmed the party line, condemning it. Opening up an old wound for those who remembered when Soviet tanks rolled into Prague, or before that Budapest.

You had heard about the invasion via car radio, driving at night on a dark country lane heading back to Sydney from your sister’s place in the country. After the news flash, the car died. Just stopped running, and on a blind curve. Electrics dead. Looking at the bright light on the horizon, your first thought was: well, that’s it then. Nuclear war. Sydney’s gone. The car’s electrics fried by the electromagnetic pulse. You sat with that thought for a bit. Then questioned it. The flashlight still worked, so you got out and looked under the hood. A cable had come off the battery.

You became the repository of many stories. The comrades bore the scars of a series of defeats, some world historical: the Spanish Civil War, Stalinism, the Sino-Soviet split, the massacre of the party and many others in Indonesia, the failure of the new left, the coups against Nkrumah in Ghana, Allende in Chile. Some more local, such as the party’s failed attempt at a general strike in 1948, and the loss of some of its considerable power in the union movement in the cold war decades. You felt these personally.

You also heard tell of more local struggles. How the coastal shipping was unionized—after lights out, with fists. How the party fought evictions in the depression by destroying the property the bailiffs came to claim. Or how Bob Hawke, a future prime minister, drunk as a skunk, pissed under the table at a May Day function in the Namatjira Room of the Newcastle Workers’ Club.

You divert yourself from yourself with politics, but then the diversion within the diversion, of political art. A predictable turn for a petit bourgeois rebel like you. A chance encounter with Maurice Nadeau’s History of Surrealism laid out a key moment in the tension between political and aesthetic revolution. You go looking for that confluence.

You were the first from your high school to find the punk rock scene at the Grand Hotel on Church Street, same street as your father’s architecture practice. There was only one good band—Pel Mel, who played every weekend. Some of their songs are still in me.

It is in the space between the political and aesthetic radicals of our old hometown that you met Glenn Hennessy. Just a couple of years older, he wants to fuck you and you know it. But he also cares about you, takes you seriously as someone who reads, who thinks. He makes you meals for the conversation. Glenn is both gay and Aboriginal and is opening up your awareness to both those worlds a little. Please do better to treasure him. “Am I gay?” I know you ask yourself. Sure, some people just are, but for others, for you, the self can be a lot of things, and can change. Maybe there really is nothing but fiction and property holding the self together through time.

I know you will understand that last sentence. You have already read enough Marx to see how property shapes and sorts everything. You’re teaching yourself French by translating Rimbaud and have puzzled out the phrase “Je est un autre” as “I is an-other,” selving as othering. Together through the decades we will vary, elaborate and amplify these discoveries. It’s just fiction and property that bound the self and bind it to a line through time.

But if that isn’t true, could we even know it?

Anyway, Glenn isn’t the first or last man who will want to fuck you. You know you’re vulnerable to that attention, which is sometimes benign and sometimes not. You need to feel seen, feel held. You also need to feel feminine. There are ways that this need is exploitable, and you won’t always know how to get what you need from these transactions.

I’m not going to say you are a girl, or that you always were. You’ve been reading transsexual memoirs on the sly already and not finding yourself in that “born in the wrong body” story. You feel like your body is already a girl’s body. Sure, you envy the bodies of other girls, the curve of hip and tit, but lots of girls have feelings like that. You feel like it’s your self that’s too male, not your body. The properties that bind include gender. Maybe some sorts of transsexual people “always knew,” but you didn’t. You’re always swerving, blindly falling through gender.

For a long time, I “forgot” about this story. I wonder if you’ve already pushed it out of memory:

The first trans women you met were streetwalkers. Or so you assumed. What did you see when you saw them? When you were nineteen you discovered, by accident, Premier Lane. It’s one of those mystery streets of Sydney. The city ambience you love. Dark and narrow and with no obvious reason to exist. Some eighteenth-century colonial surveyor’s folly. You have been in Sydney about a year. You are going to Macquarie University on the boring north shore, so you drive over the Sydney Harbour Bridge to the east side for fun. It can be hard to park a car, so you look for those secret spots. That’s how you stumble on Premier Lane, the trans sex worker stroll.

You’d been dancing in Darlinghurst. Came back to fetch the car and found three girls sitting on top of it, two on the roof and one on the hood, singing along to a transistor radio. “She’s got—Bette Davis eyes!” They leaped off quickly, apologized. You told them you didn’t mind. They stood their ground though. With a steady gaze, they read you. The trio all rocked the same look. Long hair, short skirts, red lips, fishnets. Wiry, thin, boisterous. About your age. The frames of their bodies so like yours. Speedy: you know from speed already. Talk all jitter-chatter. Big hollow eyes, wide and dark to swallow all light. You’ve left me no clear image of any of them in memory as their talk cut and wove between kinetic bodies, dancing and singing. “Bette Davis eyes!” Teetering heels on the steepish rake of the lane. They ask you if you want to party. You decline.

They make you anxious, on layered levels. They see your sort. They expose your own contradictions, inhibitions, prejudices. About sexuality, about sex work, about class, about gender, about your inability to think at all about who you might be or who we might become. All the things you find so many ways, useful and not, to avoid thinking and feeling. You feel seen, but also like a voyeur whose glance alights by accident on that scene that looks back at you.

You will become me when it seems like you can—and not die. If you are in receipt of this letter—we made it.

Maybe I shouldn’t tell you anything. Maybe it’s just random, how we get through time. Or maybe it’s like a jazz solo—points chanced through harmonic space, picked out by the player from all the possible others. We love the small-group jazz of Miles, Monk and Coltrane. Jazz is an adventure of connecting one moment to another. (Time is an-other). I know jazz is already a guide for you. Since you not only left Newcastle for Sydney but dream of leaving Sydney for New York, jazz—all of Black music—is a good way to learn the secret history of America.

Let’s say no more of what happens, in the drifts and riffs between the times of you and of me. Who even knows if memory is any more reliable than anticipation? The mistakes we made only multiply. They are all we have. And they lead you to become me. Our mistakes are us, you and me. But you are going to hurt Mu. There’s nothing I can do to stop that. It’s one of the few things we will regret while we breathe.

Little Richard heard the call in Newcastle. Some say this happened in Sydney, some say Newcastle, which for our purposes is a more interesting story. On the waters of the harbor, on the ferry—the punt as we used to call it. She thought the call came from God. And maybe it did, or maybe from another deity. She told her bandmates God was calling, right there on the punt, on the water, calling her to change her ways. They said if she is serious that she should cast her precious diamonds and pearls into the waters. And she did.

I keep saying that you won’t want to listen to me—but can I listen to you? I’m trying. Older people can lose track of what was vital in our younger selves. That sound of surprise, shock and delight in life. Everything of note sounding out clear, not bound in worn chords of memory. I see my peers hide out in nostalgia. Seeing the same old bands, gone slack, bald and bored. You aren’t bored with life, and neither am I. Honestly, if one has a capacious relation to one’s various genders, one could transition just to save oneself from boredom. To be restored to curiosity, even to unpleasant surprises. Changing sex edits your relation to a lot of things. Including history.

Since I transitioned, I’ve recovered some of your electricity, that lust for life from which you were then also too often detached. From which you divert yourself, with various ambitions, personal, aesthetic, political. I’m trying to bring that into this writing. I’m trying to listen for you, still in me. As you’ll see from these other letters, I’m trying to wind back through the wounds. The writing writes us. Writing is the birth of the author; the text is the afterbirth.

Little Richard lost her rings. Later she’d joke that down- under fish have them. I have them now. Well, metaphorically, at least. The sparkle of one’s difference. The thing I wandered off in search of, in a manner of speaking, was right here, in the waters of home.

__________________________________

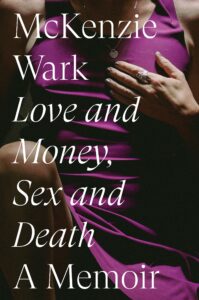

From McKenzie Wark’s Love and Money, Sex and Death: A Memoir, available from Verso Books. Copyright © 2023 McKenzie Wark

McKenzie Wark

McKenzie Wark is the author of A Hacker Manifesto, The Beach beneath the Street, The Spectacle of Disintegration, Molecular Red, Capital Is Dead, as well as the popular introductions to contemporary thought General Intellects and Sensoria. In 2017, she came out as transgender. Since, she has published her trans autofiction books, Reverse Cowgirl and Raving, and a work that combines memoir and literary criticism about Kathy Acker, Philosophy for Spiders. She teaches at Eugene Lang College, the New School.