Maya Lee on the Unique and Fraught Position Her Mother Held During the Holocaust

“You could lose your own life to a bored or disgruntled guard.”

Very few can understand what it was like to be a prisoner at Auschwitz–Birkenau—really only those who were there. Fewer still can understand what it was like to be forced into the role of “prisoner functionary” within the concentration camp. To find yourself in a position in which, if you were brave and clever, you might be able to save a few lives… while being powerless to prevent the ongoing slaughter of most of those around you. To live with the constant awareness that, at any moment, you could lose your own life to a bored or disgruntled guard who perceived that you were being too kind to a fellow prisoner, when all you were doing was trying to be humane.

My mother, Magda Hellinger Blau, was one such prisoner, though for most of her life few, including most of her family, knew her story.

Magda was always an enigma. Despite all she went through, she was not like so many other survivors of the Holocaust who displayed the emotional scars of the experience for the rest of their lives. Magda was always forward-looking, positive, and industrious. As my sister and I grew up, she would tell occasional stories of the concentration camps and her unique role within them in the same matter-of-fact way that another mother might tell stories of growing up on a farm. We had no idea. Eventually, we would just roll our eyes and say, “Just leave it alone, Mum.”

In the end, without telling any of us, she wrote and rewrote her story by hand. She finally employed a young man to transcribe her words into a typed manuscript, and only then did we have the chance to read them. But Magda wasn’t interested in feedback or clarification. In 2003, at the age of 87, she took the file to a printer and had it produced as a slim book. She organized a book launch to support a charity she was involved with and sold a number of copies. And that was that.

As my sister and I grew up, she would tell occasional stories of the concentration camps and her unique role within them in the same matter-of-fact way that another mother might tell stories of growing up on a farm.

For the final years of her life, my mother wouldn’t be drawn on her story or on the topic of the Holocaust at all. Though there was more of the story to tell, she’d had enough and wanted to move past the nightmare of collecting her memories. It was as though the act of writing it down had cleared her mind of any deep, smoldering trauma. She reverted to the mother I had known previously—the one who only ever looked forward with purpose.

It was only after her death not long before her 90th birthday that I started to appreciate the complexity of my mother’s story. In the late 1980s and early 1990s she had provided audio and video testimonies to the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Israel, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne, and, a few years later, the Shoah Foundation founded by movie director Steven Spielberg. She spent hours being interviewed for these projects but barely mentioned them to us.

As I watched and listened to these recordings, it became clear that in her haste to get her story printed, my mother had omitted a lot of detail. She had also left out numerous primary sources that amplified her story, including the testimonies of some of the many women whose lives had been saved by Magda’s careful manipulation of the Nazis. I realized that Magda had told only a fraction of her story in her own writings.

In the years since her death, I’ve become increasingly committed to gaining a better understanding of what Magda and those around her went through. I’ve discovered a remarkable and unique story of a woman who had a rare, close-up perspective on the SS (the Nazis’ elite paramilitary Schutzstaffel) and their murdering, lying, and deceitful tricks, who somehow found the inner strength to rise above the cruelty and horror of the most notorious Nazi concentration camp, and who over three and a half years was able to save not only herself but also hundreds of others.

Little has been written about the people like Magda who were prisoners themselves while also holding positions of responsibility, at the behest of the SS, over other prisoners: the so-called prisoner functionaries of the concentration camps. What has been written tends to focus on the Kapos, who had particular responsibility over the Kommandos—the working groups who performed slave labor for the SS. Most of the Kapos were German prisoners, usually hardened criminals, who had a reputation for enormous cruelty. Unfortunately, this reputation meant other prisoner functionaries were tarred with the same brush.

Magda has been misrepresented and judged unfairly by some survivors simply because of the positions she was forced to hold. Most of the accusations have relied on hearsay to denounce and condemn. In the early years after the Holocaust, Jewish survivors sought to challenge those who held such positions because they needed someone to blame. Many, including Magda, were accused of collaborating with the Nazis. This culture of finger-pointing has caused most people who held functionary positions to maintain their silence to avoid prompting further accusations.

I realized that Magda had told only a fraction of her story in her own writings.

However, to judge Magda or any of the other functionaries is to ignore the fact that they put their lives at risk every time they took some action that saved another’s life. Their stories need to be told.

Magda never sought thanks from those whose lives she saved—simply acknowledgment that she had done whatever she could in a truly horrific time. What she also wanted, as do so many other survivors, was to hold those who would deny the Holocaust to account. In her words, “I have often wished for the chance to ask these people why they deny my suffering and discredit my life and that of millions of others. Did we not suffer enough that we should now have to listen to such denials?” She also, like so many others, wanted to ensure that the Holocaust could never be repeated.

*

In closing this introduction, I would like to share the following extract from an open letter by Auschwitz survivor Dr. Gisella Perl. The letter was published under the headline “Magda, the Lagerälteste of C Lager” in the Új Kelet Hungarian-language newspaper in Tel Aviv on July 28, 1953. Dr. Perl was a Romanian Jewish gynecologist whose family was separated and deported to concentration camps in 1944; she later published her own account of the camps under the title I Was a Doctor in Auschwitz. The letter was written soon after Dr. Perl had reunited with Magda Hellinger by chance in Israel.

We have only been in Auschwitz–Birkenau for a few weeks. I only guessed it then, but now I know for certain. We, numbered or not, degraded beings, human beasts—we had no idea, no understanding of what was happening around us. What was the truth? What was deception? Who is one to believe? Who is it who directs this hell? What rules and regulations govern the fate of each minute and hour?

We simply do not know. I did not know.

I have been a prisoner for six weeks. I stood barefoot in rags at the roll call and watched. I looked and observed. The camp had a few prisoners in charge and there was one called the Lagerälteste. I started watching her. I saw her with the eyes of a doctor, a psychologist. Under the hard features—that hard face she forced upon herself—I saw the fear in her eyes, the trembling in her fingers, and the terrified pulsation of the veins in her neck when

the prisoners strode in front of an SS woman or an SS man. “Who is she?” I asked.

One evening I went to see the Lagerälteste, whose name was Magda.

“Who are you,” she asked, “and what do you want?”

“I am a physician. I would like to have a pair of shoes and to speak with you,” I said with trepidation and eyes averted.

“Come in, sit down. I’ll organize you a pair of shoes, but first we will talk because I can see I am dealing with an intelligent person.” As Magda spoke she revealed the complex and devious laws of the hell of Auschwitz–Birkenau. She revealed to me the horrors of the gas chambers, the crematoria, the experimental Block 10, the horrors of the “punishment” commando and of other institutions. Ten years later I do not think people could imagine that these things existed, though it was not so long ago. They could not have imagined that hundreds of Poles and millions of Jews were murdered in this sadistic manner.

Magda talked and whispered while her face changed from one minute to the next. Instead of the hard lines, her face filled with tear-filled furrows.

“They always select a few people from our group—quite at whim, without rhyme or reason—and place them in so-called leadership positions, to be the connecting link between the murderers and the victims. Why? What for? We do not know. We only know this, that we are responsible. We are responsible for everything the SS do not like. Believe me, it is very difficult.”

She continued speaking with her head bowed.

“You are a doctor. Look out! Do not forget you are a doctor. Look out and do not forget. Whatever the Germans say, it is a lie. There is always something evil behind it. Here are your shoes. Come along sometimes and let us discuss things. We can help a great deal.”

This was my first meeting with Magda. In this way she introduced me to the reality of the horror. I watched her for a year and felt sorry for her for a year. I went to her whenever there was trouble and she always helped me.

I knew it then and I know it now: it was a bitter fate to be Lagerälteste, to hold together 30,000 to 40,000 human beings degraded to the level of animals, to keep them in order while at the same time carrying out the fiendish commands of the SS supervisors . . .

. . . Our Lagerälteste, our Magda, was a righteous person. She fought like a righteous person. I thank providence that our Magda was like that, someone who believed and had faith that someday we will become human again. Someone who, everywhere and at all times, helped us with kindness, defended us and saved us—sometimes with harshness and sometimes smiling or frowning.

I feel that with this testimony I am repaying a debt of gratitude in the name of very many prisoners—and not least in my own name—to whom Magda, the Lagerälteste at Auschwitz–Birkenau, had shown so much kindness.

I hope Magda’s story will provide inspiration to a world in which the best of the human spirit triumphs and survives under the most horrific, trying, and inhuman conditions.Maya Lee

_____________________________

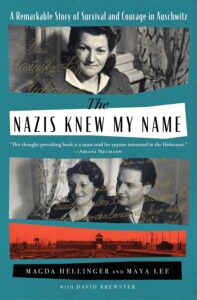

Copyright © 2022 by Magda Hellinger and Maya Lee with David Brewster. From The Nazis Knew My Name: A Remarkable Story of Survival and Courage in Auschwitz by Magda Hellinger and Maya Lee with David Brewster. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Magda Hellinger and Maya Lee with David Brewster

Magda Hellinger was deported to Auschwitz on the second transport from Slovakia in March 1942, at the age of twenty-five. She was one of the very few to survive over three years in concentration camps. During her time in Auschwitz-Birkenau she held various prisoner functionary positions and had direct dealings with prominent SS personnel, using her unique position to save hundreds of lives.

Maya Lee is the daughter of Magda Hellinger. She is an accomplished businesswoman and fundraiser with several nonprofit organizations. After coauthoring an autobiography of her Holocaust-survivor husband, she encouraged her mother to document her own story. Maya subsequently conducted wide-ranging research to fill out her mother’s story. The Nazis Knew My Name is the result.

David Brewster is a Melbourne-based freelance writer whose work is centered on helping memoirists tell their stories. David’s published works include Scattered Pearls, cowritten with Sohila Zanjani, and Around the Grounds, cowritten with Peter Newlinds.