May Day Lit: Communism and After

On the Occasion of International Workers Day

Failed state experiments in authoritarian communism can lead to pretty good literature and excellent hockey players. On the occasion of May Day, here are some our favorite examples of the former.

The Joke, Milan Kundera

We went outside. He asked me if I wasn’t afraid of being seen with him. I told him he was a fool for asking and a bigger fool if he thought his letter was going to reach its destination. He replied that he was a Communist and was required to act at all times in a manner he need not be ashamed of. And again he reminded me that I was a Communist (even though I’d been expelled from the Party) and should behave accordingly. “As Communists we are responsible for everything that goes on here.” I thought this laughable; I told him that responsibility was unthinkable without freedom. He replied that he felt free enough to act like a Communist; that he must and would prove that he was a Communist. As he said this his jaw trembled; today, after all these years, I can still remember that moment clearly and am more aware now than I was then that Alexej was not much more that twenty at the time, that he was an adolescent, a boy, and that his destiny hung on him like a giant’s clothes on a tiny body.

Mr. Kundera started writing the book in 1962 and three years later submitted it to Czech publishers, aware that its “spirit… was diametrically opposed to the official ideology.” It finally appeared in 1967, becoming a great success during the doomed, hope-filled weeks of “the Prague spring.” When the Russian tanks crashed into Prague, The Joke vanished from bookstores and libraries… In both The Joke and the several works of fiction he has since published, Mr. Kundera has undertaken a project with few precedents or parallels in modern literature. He strives to evoke the tone of life in a society corroded by a profound demoralization. Nobody believes what everyone must say and everyone knows that nobody believes. The fanaticism of the 50s is gone, the ideology of Stalinism has crumbled, but the power of the state remains. No other writer, to my knowledge, has so keenly drawn a Communist society in its phase of decadence. –The New York Times

The Four Books, Yan Lianke

The Child handed out the certificates one after another, asking everyone to either post them above their bed or tuck them under their pillow, and commit them to memory. Night fell, and the dusk was good. The chickens went to roost, the sheep returned to their pens, and the oxen were untethered from their plows. Everyone put away their work, and then the Child said, “In late autumn everyone must sow the fields. Everyone will be given at least three or five mu of land. On average, peasants can produce about two hundred jin of wheat per mu, but all of you have cultural ability and therefore I ask that you produce at least five hundred jin per mu. As the higher-ups have noted, the nation controls everything under heaven. The United States is a pair of balls, and England, France, Germany, and Italy are cocks, balls, and feces. In two or three years, heaven and earth will be overturned as we catch up with England and even surpass the United States. The higher-ups said that you should plant wheat and smelt steel. Everyone must smelt an average of a furnace-worth of steel every month. Given that each of you has cultural ability, you therefore cannot produce less than the peasants.

The remarkable Chinese novelist Yan Lianke has explained what he calls “amnesia with Chinese characteristics” as a state-administered loss of memory that the regime sees as essential to its survival. This amnesia, he has written, is achieved by shackling people’s minds, altering historical records, manipulating textbooks, controlling literature and the arts, and using financial incentives to entice people to give up their memories. Yan Lianke himself must count as one of this strategy’s greatest failures. No other writer in today’s China has so consistently explored, dissected and mocked the past six and a half decades of Chinese communist rule. He has never been shy of treading on the Party’s toes… His most recent novel, The Four Books, now translated impeccably into English by Carlos Rojas, has proved a step too far. Banned in mainland China, it is squarely planted in a blank passage of official history, the years between 1958 and 1962, and the catastrophic events that the party created and which it continues to try to scrub from the nation’s memory. Yan has written that The Four Books took him 20 years to plan and two to write. He wrote it exactly as he wanted to, without regard for the censor. It was rejected by 20 publishers, all of whom understood that publishing it would mean they would be shut down. –The Guardian

Snow White and Russian Red, Dorota Maslowska

They look at her, then at each other. We can check on that–one of them throws out. So they pull a black gestapo knob on a cord out through the window of the patrol car, and of them recites to Angela that poem he learned in his first year at policeman’s night school. Last name, first name, birth date and residence, house number, parent’s maiden name, show size, number of windows in your apartment. It’s an oral table for Angela to fill out. Then everything happens in turn… Then they convey what they manage to remember to their gestapo radio. And in the hinterlands of that whole system sits Big Brother, he smokes a cig and replies. He confirms that there’s an Angela, that they have her in their notes. Then he confirms the data she provided. And at the same time he adds a little bit from his own archive, That she’s been seen in suspicious company, that she’s under suspicion for the iconoclastic besmirching of the Number 3 bus, as one town resident reported, she’s the leader of the ecological opposition who rats out the municipal authorities to the government and the vegetal organizations regarding the sewage.

Maslowska’s first novel, Snow White and Russian Red, is a blustery romp through the disaffected world of post-Communist Polish youth. Stranded in a country that’s no longer Communist but isn’t yet integrated into the West, young Poles compensate for their sense of political and economic abandonment with drugs and sex. Maslowska describes their disdainful ennui in free-associative and occasionally absurdist language… Maslowska’s slacker narrator is a 20-something named Andrzej Robakoski (better known as Nails), who unravels into the arms of a succession of young women after his girlfriend, Magda, dumps him. Not much else happens; from start to finish, we’re confined within a freewheeling monologue manufactured by Nails’s drug-addled mind. (“A definitive rise in the level of carbon monoxide in the natural air,” begins his riff on a barbecue, “kielbasa its usual mother, subject to this holocaust, death everywhere, murder everywhere, hacked-up animals that, if they could, would cry out, but they can’t anymore, their mouths have already been confiscated.”) –The New York Times

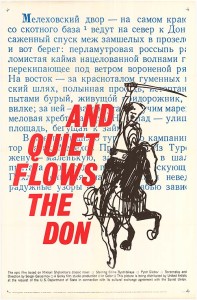

And Quiet Flows the Don, Mikhail Sholokhov

It’s true, war has gone on since the beginning of time, and will go on so long as we don’t sweep away the evil government. But when every government is a workers’ government the won’t fight any more. That’s what’s go to be done. And it shall be done, may the devil bury them! It shall be. And when the Germans, and the French and all the others have got a workers’ and peasants’ government, what shall we have to fight about then? Away with frontiers, away with anger! One beautiful life all over the world. Ah…!” Garanzha sighed and, twisting the ends of his whiskers, his one eye glittering, smiled dreamily. “Trisha, I’d pour out my blood drop by drop to live to see that day.”

Sholokhov has not been helped by the Soviet regime’s nonsensical canonization of him as a classic of Socialist Realism, by his loyal membership in the Communist Party or by his role in later years as a scourge of dissidents. But his masterpiece remains the finest realist novel about the Revolution. During the 12 years of its composition and publication, it repeatedly ran into censorship problems (unblocked by Stalin personally one or more times), and all Soviet editions before 1984 were distorted by the political exigencies of the moment, as were the corresponding translations… Sholokhov’s critics loathed his politics; supporters were indulgent of the Soviet regime. There was also the problem of the novel’s uneven quality: even admirers admitted the prevalence of poor writing, especially in the later volumes. –The New York Times

The Mother, Bertolt Brecht

When the ruling class has spoken,

the ruled shall raise their voices.

Who dares say: Never?

Who’s to blame were oppression rules? We are.

Who’s responsible where the rule is smashed? We are.

Those beaten down shall rise up tall!

Whoever is lost, fights back!

Who can restrain the man who sees his situation?

The victims of today will be victors of tomorrow

And Never is changed into Today.

Taking his protagonist, Pelegea Vlassova, from a novel by Maxim Gorky, Brecht shows how she is stirred into action by necessity: when her son, Pavel, is arrested for consorting with revolutionaries, she takes over his role distributing leaflets. Confronted by hard evidence of police violence towards striking protesters, she becomes ever more impassioned: one of the best scenes shows Pelegea and other unlettered workers learning to read and demanding to be taught useful words such as “class war” and “exploitation” rather than “fish” and “tree.” But, instructive as the story is, one sees how in his later, greater plays Brecht would go much further in exploring the cost of commitment to an idea: the scene where Pelegea is too busy printing leaflets to console her fugitive son offers intimations of Mother Courage without its gut-wrenching power. –The Guardian

BONUS READ: Don’t forget that early 20th-century socialism gave us the eight-hour work week, along with one of the finest works of long-form journalism ever written:

Homage to Catalonia, George Orwell

In the Lenin Barracks in Barcelona, the day before I joined the militia, I saw an Italian militiaman standing in front of the officers’ table.

He was a tough-looking youth of twenty-five or six, with reddish-yellow hair and powerful shoulders. His peaked leather cap was pulled fiercely over one eye. He was standing in profile to me, his chin on his breast, gazing with a puzzled frown at a map which one of the officers had open on the table. Some thing in his face deeply moved me. It was the face of a man who would commit murder and throw away his life for a friend—the kind of face you would expect in an Anarchist, though as likely as not he was a Communist.

That [Orwell] could have written so objective a book so soon after his almost fatal involvement in the war itself and in the partisan conflict seems miraculous. For that matter, it is remarkable that he wrote the book at all. Orwell was not the only man to be disillusioned with communism in Spain. Koestler’s disillusionment began there, and he let it find expression in his first novel, The Gladiators, but he did not talk then about what he had seen in Spain. Dos Passos, already far on the path of disenchantment, was deeply troubled by what he saw and heard, but he was cautious in voicing his doubts. There were others, too, but almost all of them were silenced by the fear that they would damage the Loyalist cause. Orwell recognized no times and seasons for telling the truth; he spoke out. –The New York Times