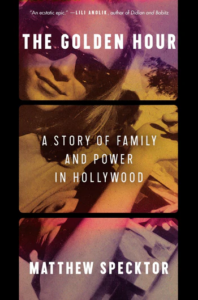

Matthew Specktor Remembers His Mother as a Young Woman Struggling to Find Her Place in Los Angeles

“All of this suggests not a person who’s simply afraid to be late, but rather one who is running: who remains, always, in flight.”

My mother is waking up. In her bedroom on Chelsea Avenue, in a carved-up duplex in Santa Monica, she stands and paces through the morning’s cloud-bound whiteness, the fog that has drifted in off the Pacific. All over Los Angeles, in Santa Monica and West Hollywood, Toluca Lake and Valley Village, there are women like her: beautiful women with headshots in their closets and refrigerators clustered with Tab soda and cottage cheese, women with stage names they hope will launch them to stardom.

My mother has had such a name, also, as she was once Katherine McKenna (modeling), then briefly Katherine Froelich (marriage), before reverting to her birth name, McGaffey. But at twenty-seven, she has given up those dreams. Her headshots are up in an attic somewhere, glossy black-and-whites in which she appears almost doll-like, although in real life her smile is warm and convivial, her eyes a piercing, seawater green. No man has ever accused her of not being pretty enough, not even the husband who’d left her, alas, for other reasons.

If she could, she would read all day, or—she cannot quite admit it to herself—write.

In the kitchen, before the rumble of rush-hour traffic begins, she sits at a narrow table and reads, bending over a Signet Classic. If she could, she would read all day, or—she cannot quite admit it to herself—write. She would write. She cannot admit it, because though she admires the boldness of her favorite writers—Jean Rhys and John Dos Passos, James Joyce and Elizabeth Bowen—she remains privately timid, and does not yet fully possess her own mind. Still, she bends over her paperback, smiling and shaking her head, picking up a pencil here and there to underline; her imaginative life unknown to the people around her, the ones at work, but inside it’s lively, burbling, and clear.

She reads until she can feel the light changing—she looks up to see the fog is starting to burn off—then stubs out her cigarette and races to get dressed. It is barely more than a studio, this place, with its cramped and shady sitting room, its crooked kitchenette. She grew up in splendor, as for a while her parents had owned a house on McCadden Place that had previously belonged to Judy Garland, but now she and her mother barely speak. Her older sister, Marge, is a secretary at Hughes Aircraft in Fullerton, her older brother, Don, a municipal worker in Pomona, and she remains in exile from the expensive world into which she was born, a world that had dissolved itself even before her father died, as the family had lost all its money.

She is alone, divorced, employed inside the motion picture industry, and she knows that the job she has, secretary, isn’t going to lead anywhere but that she doesn’t particularly want it to. She likes movies fine, but she isn’t obsessed or enthralled by them. Sometimes she wonders, as she picks up the telephone and catches the sound of a familiar voice (“Hold on one moment, Mr. Brynner, I’ll connect you”) whether they sound as strange to themselves, these people who buzz in her ear all day. It’s not that they aren’t friendly or polite, it’s that even when they flirt, they seem mostly to be talking to themselves. Perhaps this is her quarrel with the movies, why she likes them less than literature: because they are like one-way glass, where fiction is a welcoming room, one that bursts into life the moment you step inside it.

She dresses quickly. Her oblong, Scots-Irish face may be too idiosyncratic for the screen anyway, the hollow cheekbones and sharp eyes, the straw-blond hair worn in a low-slung and slightly disheveled beehive. Over the course of her life, she will assume a succession of roles—wife, mother, activist, administrator—some of them closer to her original dream than others, but none of them will suit her perfectly. She will carry with her a certain ambivalence, trying things on and abandoning them, moving on to whatever is next.

Decades from now, her closet will hold a leotard and several pairs of shredded ballet shoes; a baby grand piano will sit in a corner of her living room, its keys dusty; the scraps of her life as a serial spouse and parent, both of which may prove more challenging to her than a layperson’s mastery of dance and music, will litter her house and yet it will be books, walls of them, that dominate, not one of them bearing her own name.

Oh, well. There is plenty of time left to make her mistakes, plenty of opportunity for her yet to miss. Her life is like any other young person’s: still golden, more so than most because she has grown up with all the advantages of whiteness and money, with private schools, with swimming pools and a beach club membership from which her father, the late Mac McGaffey, had ultimately resigned in liberal protest of the fact they didn’t admit Jews. Her trauma—poor Mac had dropped dead right in front of her when she was just fourteen—is ordinary. Nothing marks her, nothing evident to the naked eye: her divorce was clean and left her anything but heartbroken once the circumstances were clear to her. But the quickness with which she grabs her purse, darts back into the kitchen for her cigarettes, races through the clutter of her sitting room and then out, down the front walk to her car: all of this suggests not a person who’s simply afraid to be late, but rather one who is running: who remains, always, in flight.

*

“Ira Steiner’s office?”

She sits at the end of a long row of secretaries now, perched outside a corner office at 9255 Sunset Boulevard.

“One moment, Mr. Lancaster. I’ll put you through.”

The women line up in almost identical profile—all of them pretty, most of them pale, heads angled against telephone receivers and hovering over typewriters, hands clutching cigarettes, coffee cups, and cans of diet soda—flanking a long corridor on a high floor of a mid-century modern tower. The carpet is mustard-colored, the air gray with smoke.

“Ira Steiner’s office?”

Perhaps this is her quarrel with the movies, why she likes them less than literature: because they are like one-way glass, where fiction is a welcoming room.

Flight, too, is in her blood. This city is also famous for its other dominant industry, aviation. Her uncle Neil had owned a small company that designed planes for private ownership, a prototype called the McGaffey AV-8, back in the thirties. Her great-grandfather, a lumber magnate who was one of the wealthiest men in New Mexico, had died in a commercial crash in 1929, among the first in American history. And yet here she is working for a medium-sized talent agency, having gone to UCLA instead of to secretarial school like her mother suggested because, according to Helen McGaffey, the only future that means anything must involve her finding a husband. Helen, my grandmother, is a blueblood, an old-line American whose ancestry can be traced all the way back to John Alden of the Mayflower. She and my mother are just at the beginning of a quarrel that will last several decades. Here, at least, my mother feels insulated. The hungry young men and women of the Ashley-Famous Talent Agency are a far cry from Helen’s prim, Protestant frigidity.

“Ira Steiner’s office?”

The repetition of it might bore her to death. But she is good with monotony, in fact likes a little numbness, as she does crossword puzzles, sums and figures (her father was an accountant), driving, anything that invites hypnosis, an anonymizing process in which it is possible for her to disappear. When she was seventeen, she’d taken a blade and slashed at her wrists. Two pale scars commemorate this event, which she will never explain to me.

Eighteen months before this, her father had died. They’d been sitting in her family’s house on Esparta Way shortly before her sixteenth birthday, waiting for the Sammy Kaye Variety Show to start, when Mac got up to prune his flowerbeds in the twilight. He’d stepped out the sliding doors, his hulking, football player’s body—he’d been a star at Cal Tech—looming against the evening sky. She’d looked back at the TV a moment and then heard it: his shoulder slamming against the doors, hard enough to crack glass.

“Ira Steiner’s office?”

All these years later, she can still see his body crumpling to the concrete terrace, the shears dangling from his hand; his final words—“It’s like a wake in here”—ring in her ears, and the channel of blood that ran from his head, redder than you can imagine, often paints her dreams. But it’s not this that makes her feel she could vanish from this earth, and no one would miss her.

“One moment, I’ll see if he’s in.”

Not this, valve damage—her father’s heart like a ticking bomb, thanks to rheumatic fever he’d had as a boy—but something else, something I will never wholly understand.

__________________________________

From The Golden Hour: A Story of Family and Power in Hollywood by Matthew Specktor. Copyright © 2025 by Matthew Specktor. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Matthew Specktor

Matthew Specktor is the author of the novels American Dream Machine and That Summertime Sound, and the nonfiction books The Sting and Always Crashing in the Same Car. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Paris Review, The Believer, Tin House, Vogue, GQ, Black Clock, and Open City. He has been a MacDowell Fellow and is a founding editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books. He resides in Los Angeles.