Matthew Cheney on Literary Misdirection and Hiding Truth in Fiction

Jeff VanderMeer Speaks With the Author of The Last Vanishing Man and Other Stories

Jeff VanderMeer and Matthew Cheney first encountered each other in 1989, when a thirteen-year-old Matthew submitted a short story to the almost-as-young Jeff’s little magazine Jabberwocky, and Jeff provided a personal rejection note for a story that certainly did not merit such careful attention. The writers reconnected in the early 2000s, and have worked on various projects together since then.

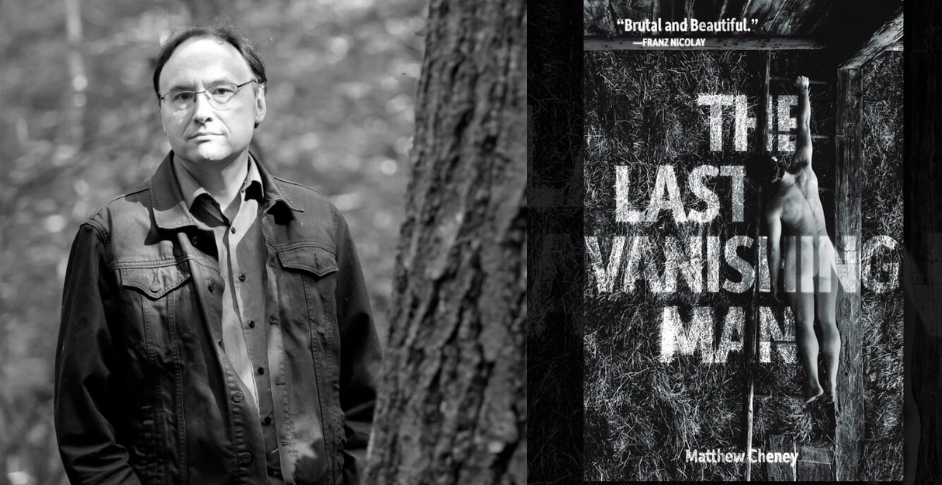

The publication of Cheney’s second collection, The Last Vanishing Man and Other Stories (Third Man Books, May 2023), provides an opportunity for Jeff to ask some questions about these strange tales.

*

Jeff VanderMeer: In “The Last Vanishing Man”—such a great title and such a crafty, marvelous story—you write, “What is memory, what is reconstruction, what is misdirection?” How do you approach, say, misdirection in your fiction?

Matthew Cheney: For a traditional magician, misdirection is all about making the audience pay attention to something other than what the magician is actually doing, the trick of the trick. For a storyteller, misdirection is about multiplicity, because the technique is right there if you want to look back on it. After the effect of misdirection, the reader can then reread and see both what they were led away from and what they were led to, and find pleasure in both.

It’s an effect I’ve loved since I was young, whether in simple mystery stories or in, say, the conclusion of Philip K. Dick’s Ubik, which completely blew my mind when I first read it as a teenager. A more recent example might be the first few episodes of the German Netflix TV show Dark. It pulls a mindbender by making us think it is one kind of show and then, a few episodes in, blasting our assumptions to smithereens and revealing all sorts of depths that were there from the start but we weren’t yet able to notice.

I’ve watched the first season of Dark three times, and it’s always thrilling, because now I have both the ultimate story itself and the moment-by-moment experience of that story setting up its tricks.

JV: I feel like you must think about a narrative for a long time before you write it. Is that generally true, and do you revise much from first drafts?

MC: I sometimes feel less like a writer than a seeker of patterns. The two things I need to be able to write a story are a sense of its structure and a sense of its tone. If either one is off, I can’t make any progress. I start three, four, five stories for every one I finish, and the ones that don’t get done are the ones where I can’t find a way into the patterns of sound and structure, the ones that remain murky and mumbling or fragile and tinkly.

This tends not to lead to lots of complete drafts, at least not separate drafts of big changes (I’m always fiddling with individual words, with sentence structures, with stylistic clarity), although it may lead to lots of false starts as I try to find my way in. Once I’ve got the rhythm, point of view, and an idea of how scenes work together, I’m on the home stretch.

For a storyteller, misdirection is about multiplicity, because the technique is right there if you want to look back on it. After the effect of misdirection, the reader can then reread and see both what they were led away from and what they were led to, and find pleasure in both.

The time between initial inspiration for a story and that moment of, “Aha, I’ve got it!” can be weeks, often months, sometimes years. In between sit piles of notes scratched on scraps of paper and lots time spent tossing ideas around in my head, imagining options.

JV: Did any of these stories change radically between conception and final?

MC: My original notes for “At the Edge of the Forest” were for a traditional horror story. A lot of the elements of that horror story are in the finished version—what Bryan believes is true about how he is cursed is what I originally thought was true in the story. But once I started writing, it all kept resisting an unambiguously supernatural mode. I discovered as I wrote that the story needed to allow the possibility, even likelihood, of self-delusion and false memory.

The most radical change among all the stories in the book is that of “After the End of the End of the World,” which started out as a novel. Or two novels. Two complete, very different, equally untenable drafts plus countless fragments and failed attempts over the course of about fifteen years. The story itself is less a story than an essay about a novel that never worked.

JV: In “After the End of the End of the World,” the character Jane lives many lives or potential lives, with an overlay of the intensely political. Is it tyrannical for the reader to expect one version of events?

MC: I like the word tyrannical there because it lets me claim that my fondness for ambiguity is democratic: the truth of stories like “After the End of the End of the World,” “The Last Vanishing Man,” “Mass,” and others is left to readers to decide for themselves. I don’t want that to be an excuse for vague writing and shallow imagining, though.

To avoid the vague and shallow, we can study poetry, particularly the ways poets use juxtaposition and parataxis. How we get from one word to another, one line to another makes all the difference. What the words are and aren’t, what the sentences say and don’t, what transitions exist and which transitions are skipped—that’s where meaning happens.

JV: In “Winnipesaukee Darling,” a moment where a character is buying a mixed berry smoothie has a humorous tone, as does a character later in the story claiming not to be an ax murderer because of not owning an ax. Your stories are serious and sometimes even tragic, but how do you use humor in your fiction in general?

MC: I’ve written my fair share of unrelievedly bleak stories, but I prefer to provide lightness whenever I can. It’s a necessity for the more serious moments to have any real effect. Sometimes I do enjoy the literary equivalent of a black-on-black painting or a drone song. But mostly I think we need variation in tone to create meaning.

In “Winnipesaukee Darling,” one of the characters eventually speaks for a long time about some truly shameful, hurtful things he did. I wanted that moment to have gravity—to be the gravitational center of the story—and so it needed to have lots around it to offer contrast. (It’s also the single longest paragraph in the whole book. Even visually it has heft and demands sustained attention.) We need to like this character already for his revelations to have the emotional effect I hope they do. Humor aids that contrast.

But there’s also variation between different types of humor in the book. “Winnipesaukee Darling” contains a different, more gentle sort of humor from the acidic, absurdist humor of “The Ballad of Jimmy and Myra,” a story that is something of a scream against the universe. There, the purpose of the humor is almost polemical, a satire of a culture that cheapens trauma into mass entertainment, but it’s also an expression of anger at that culture. Absurdist humor relies on grotesquerie, on deformation; anger, too, deforms, but the absurdism deflects some of the bludgeoning power of anger into a more useful and entertaining, but hardly less caustic, affect.

JV: How do you see these stories in relation to the ones in your prior collection, Blood?

MC: The first book collected stories written over a period of about fifteen years, only a few of them with any sense of being related to each other. Of course, since they were written by one person who has a limited imagination, ideas and images and even props recurred, so some order could be made of it all, but really it was just a collection of the stories I’d written that I wanted to preserve in book form.

The Last Vanishing Man is different. Most of these stories were written with a collection in mind. I am very fond of Blood, but I didn’t want to have quite so eclectic a collection again.

There are continuities between the books, however. In many ways, “After the End of the End of the World” is a sequel to the title story of the first book, and both are companions to a later story in this collection, “A Suicide Gun.” My father owned a gun shop for all the time he was alive in my life, and these are three stories of fathers with guns. Similar names are no coincidence: the woman who is the focus of “After the End….” is named Jane and the narrator of “Blood” is Jill (also the title of the new movie based on “Blood”).

I tend to gnaw at the same subject matter again and again until I chew off enough of myself to get out of the trap.

JV: Where does autobiography hide in your fiction?

MC: Some of the autobiography doesn’t hide at all. “Killing Fairies” is me attempting to write a speculative memoir à la Richard Bowes, whose Dust Devil on a Quiet Street is one of my favorite books. “Killing Fairies” is the most nakedly autobiographical story in the collection, because I gave myself the challenge of trying to invent as little as possible.

More invented, but similarly based in real experience, is “Wild Longing,” where I drew a lot on memories of a retired music professor who was important to me when I was young, and who lived to be over 100, and whose house I did, like the narrator, get to go through after his death—and found exactly what I describe in the story. (He was not, though, a forger. That’s based on another local story of forged Robert Frost manuscripts.)

In both those stories, it’s autobiographical material consciously and deliberately shaped into fiction. But as you say, lots of autobiography hides. In some stories, the emotional or psychological elements feel more dangerously revealing, like kneeling in the dark and whispering confessions, or maybe prayers. You’ll find it in what gets repeated across the stories, particularly emotionally. That’s the real stuff, the most important stuff, the stuff that most deeply connects with readers and makes reading worthwhile and fulfilling.

Fiction in particular has an alchemical power to transmute individual experience and feeling into something beyond the individual, something that moves toward a kind of collective imagining.

I am not interested in narcissistic parades of emotion, but I also recognize that fiction in particular has an alchemical power to transmute individual experience and feeling into something beyond the individual, something that moves toward a kind of collective imagining. Humans have always told stories. It’s one way we know each other.

JV: Do you consider yourself to write traditional stories in the sense of structure? I say this as a compliment in that they seem subversive in many ways but also timeless. I had the feeling reading them that I could pick up the collection in fifty years and they would not have dated.

MC: Yes, as much as I wish I were a radical experimentalist, my sense of story would be more or less familiar to a reader from the late 19th century. And yet…my sense of structure seems a bit at odds with both literary and genre standards, as does my sense of what a story can be and do.

My influences are different than those of most short story writers, and that may explain it. I draw as much from plays, poetry, and music as from other works of fiction. Aesthetically, I think I’m more aligned with contemporary playwrights like Sarah Kane, Suzan-Lori Parks, Len Jenkin, and Christopher Durang than I am with most fiction writers.

Their work left such strong impressions on me when I was young that it became my deep grammar. Most of what I think about character comes from A Practical Handbook for the Actor, not a writing manual. In fact, that book would be a good one for any writer to read who wants to learn more about characterization.

My first three years of college, I was at New York University studying playwrighting, and even though my interests have moved in other directions, those were formative years. The best writing teacher I had at NYU, David Greenspan, encouraged us to think of traditional styles like melodrama as the most powerful sites for radical—and in David’s case profoundly queer—exploration. I love what Hilton Als had to say about him in 2012 in The New Yorker: “In his plays, Greenspan leaves air between the lines so that actors can find their way through the thicket of his sadness and whimsy.”

I think I am drawn to writing short stories because they offer, and I might argue at their best require, space between the lines for readers to find their way. Through the thicket of sadness and whimsy. Though in my case whimsy is perhaps most often just another word for nightmare.

______________________________

The Last Vanishing Man and Other Stories by Matthew Cheney is available via Third Man Books.

Jeff VanderMeer

Jeff VanderMeer is the New York Times bestselling author of more than 20 books including novels and fiction anthologies. He has won the Nebula Award, the British Fantasy Award, and, three times, the World Fantasy Award and has been a finalist for the Hugo Award. He is the cofounder and assistant director of Shared Worlds, a unique fantasy and science fiction writing camp for teenagers. He lives in Tallahassee, Florida.