Maternal Vertigo: Molly Lynch on Chaos, Childcare, and Civilizational Collapse

"At the very moment that you take on the greatest act of caring, you discover how powerless you are."

I didn’t plan to take my child to the ghost city. We went there spontaneously, on our way to the beach. We were in Greece, on the island of Kythira, and we’d been driving along a road when I saw the sign for Paleochora and I hit the brakes.

I knew the legend of the place because I’d written about it in a recent novel. As the story goes, the city had been built on a narrow precipice between two deep ravines to protect it from the pirates that roamed the Mediterranean. Hidden by the gorge from the view of ships, Paleochora thrived. But the famous pirate, Barbarossa, heard rumors of the prosperous city and coerced some shepherds to show him to the way. He and his raiders attacked. While the men of Paleochora were being massacred, the women calculated their options and made a horrifying choice. Rather than be taken into slavery, they threw their children and themselves over the edge.

At the end of the dusty road I got out of the car. We were the only people there. From the backseat my child called out, Is the beach? I said, Not quite.

Wind was blowing wildly. A hill blocked my view of the ruins, but I was already imagining it—a world collapsing, mothers clutching their children at its edge.

But then it’s easy for my mind to go such places.

*

Sometime in the early weeks after becoming a mother, it occurred to me that by giving birth to a baby I’d also given birth to chaos. I don’t mean that my child embodied chaos. It was more like when the baby exited my body, a dark, swarming force rushed in. By wanting to protect someone, I’d invited into my life all that I could never protect him from. I’ve since thought that part of what changes you when you become a parent has to do with the way you encounter this contradiction: at the very moment that you take on the greatest act of caring, you discover how powerless you are.

Around the life of small child, threats ripple out in concentric circles: the choking hazards and toxins in the home, the crosswalks and highways outside the home, the seas, and so many things at once alluring and treacherous, like humans, capable of kindness and stunning cruelty: out and out go the circles, through the precariousness of the times we live in, with the forces of its politics and the things at stake in those politics, such as the inhabitability of the planet itself.

It occurred to me that by giving birth to a baby I’d also given birth to chaos.In those early weeks, I became trapped between these opposing forces—protection/powerlessness—and the discord vibrated through my being. I couldn’t sleep beside my child for fear of what might happen if I closed my eyes in his presence. When my husband took over and I slept in another room, it was with white noise, ear plugs, a duvet blocking the crack in the door, and I was still prone to waking up from the slightest creak of the floorboards, adrenaline coursing through me, heart pounding, claws out, teeth bared. It was true that my child and I had both almost died during labor, and that event had most likely left me with a touch of PTSD. But there was a deeper unsettling in me. It came from my new dilemma: becoming the guardian of a life, in a universe where I had basically no control.

We talk about postpartum “depression,” but after comparing notes with other mothers, I’ve come to think of that language as limited, if not misleading. Postpartum “total psychic reconfiguration” feels closer. But you could get even more specific, finding language for the initiation ritual in which you become acquainted with and humbled by the forces of chaos that determine so much of our lives.

Ideally, when you have a child you grow a thick skin and a good sense of humor. But it could easily go the other way. You could grow more anxious, more desperate to control environments, more edgy when the “chaos” creeps in. The steady, low-grade tension might be enough to make you want to flee.

*

Before we went to Kythira, my son and I met up with family and traveled to the island of Syros. One windy day, we went swimming in the sea. The waves were big for a four-year-old, but he dove in joyfully, floating on his belly, spreading his arms out like wings. Finding ground with his feet, he came up gasping, wiping wet hair off his face, then he dove back under. He did this over and over while I followed. We were far from shore, but the water was shallow, spread across vast, flat plain. No drop-off, no undertow, but something else was there. I saw it.

A big wave broke over his small body and for a moment he was hidden by the churning water. I saw that if I let him get too far and if he got knocked over, I might get confused by the waves. There were so many. I saw how they would keep coming, keep breaking, indifferent to me and my search for him.

That didn’t happen.

We returned to the beach, to the company of others, and wrapped ourselves in towels and ate biscuits and apricots and gazed out at the restless sea.

A few days later we said goodbye to Syros, literally, calling out, Goodbye Syros! while waving from the window of a fast ferry bound for Piraeus Harbor. We settled into row seats and my son listened through headphones to British actors reading Beatrix Potter stories. Beside him, I scrolled through the world’s bad news. I read about temperatures in the southern United States being hot enough to cook you alive and people being without power because windstorms had destroyed parts of the grid. No power meant no air conditioners. I read two separate stories, one about South Africa and one about Lebanon, where people had limited access to electricity and where they were increasingly arming themselves. I squinted my eyes so that the text blurred in front of me. I imagined this as the early throes of something that would become common, as governments operated more like private corporations and organized crime rings, and as feeble democratic institutions went down like dominoes.

Just a thought.

I looked around at the rows of Greek families and people on holiday and I tried to picture the world as it would be when my four-year-old turned fourteen. Or twenty-four. I found it impossible to see.

Through the window of the ferry I could see the small white houses of a picturesque village up on the hill. I tapped my child and pointed. An island! he exclaimed, his voice full of awe.

*

When our ferry reached Piraeus, we descended with a large crowd into the belly of the ship. Steel ramps clattered down and we began to move with a few hundred other humans. I had our luggage. I said to my child, Please keep your hand on this suitcase. He did at first, but there was a lot of shuffling and I had to look where I was going and when I looked down, he was gone. I scanned a thicket of bodies, baggage, people hurrying as a herd, but there was no sight of him. My heart began racing. I called his name sharply. Then I spotted his blue and white train engineer’s hat, his round eyes looking in the direction of my voice. People made space as I pushed my way toward him. I said, I need you to stay beside me!

*

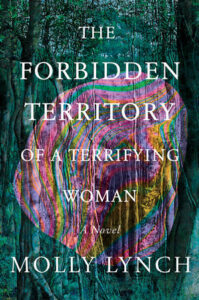

In my novel, The Forbidden Territory of a Terrifying Woman, mothers do flee. Against a backdrop of climate catastrophe, mothers around the world begin to dissociate and to spontaneously walk away their homes, their jobs, their families. This might seem like a sci-fi scenario, but the novel is actually a domestic drama, with the narrative centering on a family as they navigate the emotional fallout of the mother’s vanishing and her attempt to reenter their lives.

During the question-and-answer period at a recent book event, an audience member asked me if I thought of the novel as a postpartum allegory. The story no doubt explores questions about motherhood, but that particular allegory hadn’t been my intention. In fact, no allegory had been my intention. I had treated the story as a simple documentation of a family’s experience of a crisis affecting the wider society. I hadn’t treated that crisis as a metaphor. Instead, I imagined the mass abandonment of mothers as a symptom of a larger problem. In my own conception of it, the epidemic of mothers walking out on their civilization is the sign of a limit of that civilization, a sign of a breaking point. The mass abandonment is thus caused by something affecting us all.

But after being asked the question, it struck me that the existential disorientation of our current times are themselves like some postpartum allegory—these times being ones when, if we choose to look, we all might all recognize the vulnerabilities, the breaking points, the limits of the world we’ve designed. Times in which we consistently refer to things being “unsustainable” resemble that postpartum self-reckoning.

Ideally, when you tune into the threats you have no power over, when you recognize how helpless you are in the face of those threats, you’ll grow a thick skin and a better sense of humor. But this, too, could easily go the other way.

*

After visiting Syros, we traveled to Kythira, an island where my husband’s family is from. My husband couldn’t come with us this time, so we went without him to stay with family in a valley of olive and almond and orange trees. A place with ancient ruins and giant snail shells and lizard skeletons and luminescent pink butterflies. You can pick wild thyme in the fields and say hello to goats. The neighbor brings over fresh cheese from sheep’s milk that she has whipped with a hawthorn branch. She gives you a satchel of olive oil rusks and she suggests eating these with the cheese. At night you all sit on the roof, or in a garden, with cold wine under blazing stars.

I rented a car and took my son to villages and bakeries and beaches. We met up with family at restaurants and at a Sunday market where people sold varieties of honey. Then one day, on our way to a cove, I saw the sign for the ruins of Paleochora and I hit the brakes.

*

For a moment I thought I’d gone far enough. It would be better to come back on my own, another time. But my child was calling to be let out and then I was leaning in and unbuckling the straps of his car seat.

He asked where we were, and I told him it was an ancient city. A ghost city, I said.

He looked up at me and said, Real ghosts?

I explained that this was just what people call a place where no one lives anymore.

We walked along a narrow path with prickly thorns that scratched his bare ankles and at first this consumed our attention.

Then I saw the ruins. Stone structures with gaping black doorways. A crumbling portion of a wall with battlements at the top. All around the site were overgrown bushes, wild herbs, wild wind, and a cliff edge, its deadly drop forming the perimeter of the town. The path led away from the cliff, toward the abandoned entry. We went through it, into the places where people had lived. Around us were broken stone walls, everything falling into the earth. This was one of countless ruins in Greece—too many for the state to preserve. Eventually none of these walls would remain.

As we looked around, my child asked why nobody lived there anymore. I said nobody really knew, that people told different stories about the place. I said, Maybe they decided to live somewhere else. Or maybe something happened that caused them to leave. Then I said, Some people think that pirates came.

Are pirates real? he asked.

Nature’s forces don’t care about your civilization, whether it gets destroyed by foreign invaders, or you destroy it yourself.This child often went around saying, Shiver me timbers! but my mind was going other places. I’d heard about modern slaves held on shrimping ships and human chattel markets in Libya and Canadian mining companies coercing Indigenous communities off their land and I tried to figure out my definition of pirate. Was a pirate just a thief or did they always have to use threats of violence? Was a person a thief even if they found legal justifications or loopholes for their thefts? I was always, in some way, feeling aware of the world’s billionaires who profited from epic exploitations of human life and of the planet, and I said, There are still greedy people who do mean things. Yeah, I guess pirates are real.

My son climbed around the ruins. He scrambled up onto a wall and sat in the frame of an old window. The wind whooshed around us and I felt nervous and that nervousness seemed appropriate.

I called to him, and we entered a room with two standing walls and porticos with remnants of frescoes. The faces of saints and saviors were still visible. He got close to them, studying the ancient paintings, images of the peoples’ ideas, sacred images, symbols they had put their faith in. Whole chunks of these frescos were crumbling off and turning to dust in the soil below.

Then we went to the edge. There were still low stone walls between our bodies and the drop, but I didn’t trust these walls and I said, I need you to hold my hand. On the opposite side of the ravines were the opposing walls of the gorge. The view was stunning and terrifying at the same time. The thing that had allowed this city to thrive, was the danger that had been built into its very design.

I knew the story of the women throwing themselves over with their babies was maybe only legend, and likely a xenophobic one, told by Greeks about their heroic women who would rather die than be taken by foreign invaders. I knew there were other versions of what happened and that there may never be definitive proof of what had caused that civilization’s end. But as I gripped my son’s hand and looked down, I saw the flat fact that it had ended.

Locals say this gorge is haunted, but I don’t know what that means. I love ghost stories, but I’ve never known how to read them. By that, I mean, read into. The concept of the ghost forecloses interpretation. I can imagine a ghost story of Paleochora with a conclusion that fits the familiar genre. In it, it would be said that the energy of the women’s last moments, their anguish and terror, has been trapped in that gorge forevermore.

But maybe you could take this further, imagine something that might at first seem more terrifying: the thing that’s trapped in the gorge isn’t the women’s anguish, it’s the surrounding environment’s indifference to that anguish. In this version, the gorge is haunted by the fact that there’s nothing exceptional about the human experience. The waves don’t stop for you and your child. Nature’s forces don’t care about your civilization, whether it gets destroyed by foreign invaders, or you destroy it yourself.

For a moment, on the edge, I felt history collapse. It was like some fold in an accordion had closed and I was standing in the place the women had stood and nothing had changed: not the wind in the crevasses, not the uncertainty. The gravity of the earth was also the same. That force that holds us here is the same force that causes us to fall.

I didn’t let go of my son’s hand. He complained and tried to wriggle free. He felt capable of managing the trail without my help and I’m sure he would’ve been fine. But I was capable of superstition. I said, When we’re back on the flat part you can run as fast as you want.

Then I told him about good things we would do, like put on our goggles and dive for seashells and read our chapter book in the shade. And later, I said, we’d get ice cream.

__________________________________

The Forbidden Territory of a Terrifying Woman by Molly Lynch is available from Catapult Books.