On the morning of September 18, 1991, Helmut and Erika Simon set out to ascend Similaun, a diamond-shaped peak that rises into the clouds of the Italian-Austrian Alps. The hike was not easy. The weather was unseasonably warm. Glaciers blanketing the mountains were melting. Icy rivers raced downhill, carving small gullies, tunnels, and caves that dropped into blackness and the unknown.

The Simons were on vacation from Nuremberg, Germany. They threaded their way across the fields of melting ice and crevasses until eventually they stood at the top of Similaun, triumphantly looking down on the world from a height of nearly 12,000 feet. As they happily descended, daylight began to fade. They wouldn’t be able to make it back to their hotel in Vernagt, Italy, before nightfall, so they found their way to a rustic stone-and-wood lodge set high up among the peaks.

The next day broke clear and beautiful. The Simons decided to squeeze in another hike. With some new friends they had met at the lodge, the couple started out for Finail Peak. The trail took them through a barren landscape, far above the tree line. Patches of liquifying snow were spread across a broken patch of sharp fragmented stone, colored charcoal and ash. By noon, the group reached the blustery summit and then headed back down. Soon after their descent began, the new friends said their goodbyes to Helmut and Erika and took off in a different direction.

Everything that Ötzi possessed are things recognizable to us today.The Simons looked for the trail that would take them back to the lodge. They were skirting a trench when Helmut looked down into a pool of thawing snow. He saw a strange shape. His first reaction was anger, thinking it was a piece of trash marring the magnificent landscape. As Helmut’s mind caught up to what his eyes were seeing, Erika cried out, “Look, it’s a person!”

Just feet away from them was the head and upper back of a human being suspended in the slushy water. Face down, the remains were dried out, the person’s skin leathered—smooth, hairless, orange.

The Simons returned to the lodge and reported their discovery to the caretaker, Markus Pirpamer. He called the police in both Italy and Austria, not knowing on which side of the border the corpse had been found. Markus then went to investigate, joined by the lodge’s cook. After an hour’s hike, they found the body and began inspecting the area for clues when Markus noticed an object lying nearby. He picked it up and admired the long, smooth handle that turned a sharp 90 degrees like a perfect L. Wrapped at the end was a fine, symmetrical metal blade. It was an ax, but unlike any Markus had ever seen. He noticed other things too—fur and sticks and boards and a birchbark tube of some sort stuffed with hay—all camouflaged in the mud. A half hour passed. The two men returned to the lodge.

The next day, a helicopter flew out to the site, where Anton Koler, an Austrian inspector, met Markus. They began using a jackhammer to loosen the glacier’s grip on the man. Storm clouds were moving in. The men worked hard, often submerged in the icy water pulling at the body with bits of dried flesh breaking off. After all their effort, the person was only half excavated and the air compressor was empty. They went home.

Word spread at the lodge about the find, including to Reinhold Messner, a world-famous mountain climber who happened to be traveling through the region. He couldn’t resist checking out the man. With his companions, Messner tried to pry the body loose, pulling at it and using one of the sticks lying around to hack at the ice by the person’s legs. The body stayed stubbornly locked in place. But based on the artifacts and the preserved condition of the body, Messner began to suspect that this person had been hidden under the glacier for a long time.

Several days later, another Austrian government helicopter arrived to extricate the body from the ice, but the crew had not brought a shovel, to save weight on the flight. The inspectors borrowed a ski pole and an ice pick from a passing hiker to hack at the ice. After much more yanking and pulling, the glacier finally let go. The person was stiff as a board and now completely naked. Most of the leather clothing had been shorn off in the ad hoc excavations. The men scoured the area for more evidence. They found a grass mat, a whittled branch, and a knife made of stone. The helicopter flew off with the strange body and mysterious things.

On a cool, crisp late summer morning in 2019, I visited the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, in Bolzano, Italy. The museum, set along a cobblestone street with high-end clothing stores, opened in 1998 in an old bank—a fitting location for an archaeological treasure. After passing through security, we met our guide for the day, Nico Aldegani. A trained archaeologist, Aldegani had a stylish beard, and his long hair was pulled back in a hipster bun. He exuded energy and enthusiasm.

We started a tour of the exhibit hall. Aldegani began narrating the Simons’ discovery of the man eroding from the glacier. He then turned to the scientific excavation of the site in 1992, which led to a bitter dispute between Austria and Italy over control of the remains and artifacts. Eventually, it was resolved when the site was shown to be just 101 yards within the Italian border, and an international team began a collaborative phase of research.

After a few exhibit panels, we stopped before a dramatic silver metal wall that stood like a vault. A small window was framed at its center. I stepped up on a platform and pressed a button. A muted blue light flashed on, revealing a stark white refrigerated room.

On a glass table lay Ötzi, the iceman from the glacier. His spotted ochre skin looked glassy, a result of the room kept humid to preserve the body. His left arm was tucked tight under his chin, across his chest. Naked and tonsured, preserved and decayed, with only a thin rind of muscle and skin wrapped around a skeleton, Ötzi looked to me half alien, half human.

The exhibit went on to reveal Ötzi’s amazing story. Arguably, he is among the most well-studied bodies in history. Ötzi lived about 5,300 years ago. He stood five-foot-two and was a wiry 110 pounds. He had 61 tattoos pecked into his skin. He suffered from several ailments, including bad teeth, arthritis, parasites, and broken ribs and a broken nose that had healed. He was lactose intolerant and had plaque in his coronaries. His lungs were coated in soot from a lifetime of living around open fires. He was about 45 years old when he met his end.

We continued on, for the main reason I’d come to the museum: to see Ötzi’s stuff. As Aldegani said, “The man comes alive with his artifacts.”

Although some of what Ötzi carried had been destroyed in the initial struggle to remove his body, archaeologists have recovered many of his belongings and reconstructed others. Ötzi was clothed from head to toe, wearing a bearskin hat with a chin strap, goatskin leggings lined with deer fur for warmth, a sheep- and goatskin coat, a loincloth, a belt with a sewn-on pouch, and shoes made with bearskin for the soles (for strength) and deerskin for the uppers (waterproofed through tanning techniques with oils), and stuffed with grasses. He was well dressed. “It was fashion for sure,” Aldegani joked, “because it was found in Italy.”

With him, Ötzi carried a longbow and 14 arrows in a quiver, two birchbark containers (with one carrying fire), tinder fungus, a scraper, a boring tool, a bone awl, a retouching tool to make stone flakes, a stone flake, a stone dagger with an ash-wood handle and sheath made from the fibers of tree bark, a mysterious stone disk hung from strips of leather, and a copper ax. He carried all this—and likely more that was lost to time—in a backpack made with an upside-down U-shaped frame with slats and netting. All told, Ötzi carried 400 things, made from stones, minerals, 21 plant species, and the remains of a variety of wild and domesticated animals. “It’s a lot of things,” Aldegani said. He estimates that all of it would have weighed more than half of Ötzi’s own weight.

Because so much organic material typically degrades at an archaeological site, Ötzi offers a stunning view into the material world more than 5,000 years ago. He shows how far our ancestors had traveled from those first few stone tools Lucy’s species had invented millions of years ago. Everything that Ötzi possessed are things recognizable to us today—things not very different from what you likely are wearing right now (underwear, shoes) or have at home (matches, knives).

At some point between the rough stone tools Lucy’s kind used and the iceman’s overflowing backpack came the foundation for every thing in our modern world.

*

The basic tools in the iceman’s toolkit—the scraper and flaked-stone cutting tool—were invented millions of years ago; they do not look that different from the technology found at Ledi-Geraru in Ethiopia. However, Ötzi’s arrowheads and dagger are the culmination of vast technological leaps across continents and countless generations of ancestral human species.

Unlike the simple tools that can be manufactured by striking two rocks against each other, the arrowheads and dagger were made through a complicated series of steps that require striking a hammerstone precisely against the “core” and then using, in Ötzi’s case, a wooden handle with a fire-hardened antler tip embedded in the end—a tool that looks like a thick pencil—to press into the stone’s edges to shape and sharpen them. A 2018 study found that Ötzi likely sharpened the scraper and other tools just hours before his death.

A long line can be drawn from Ötzi’s stone tools all the way back to Lucy. After the initial discovery of stone technology by at least 3.3 million years ago came long periods of stasis interrupted by moments of dramatic change. Each new form of stone technology was radical and advanced, but then, as it was replaced—looking back from later years—the earlier version seems mundane and simple.

Houses, paint, sculpture, body ornaments—our distant hominin ancestors were starting to make our material world.That Lucy’s species realized sharpened stones could be used as tools was a profound discovery. These tools lasted almost a million years without much change. But then came the Oldowan toolkit, around 2.6 million years ago, and this combination of tools—used to make more refined tools—was a game changer. More attention was given to flaking off finer pieces of stone that could be used to cut and scrape, while the cores could be used for chopping as well as for hammering. The Oldowan technology lasted nearly another million years.

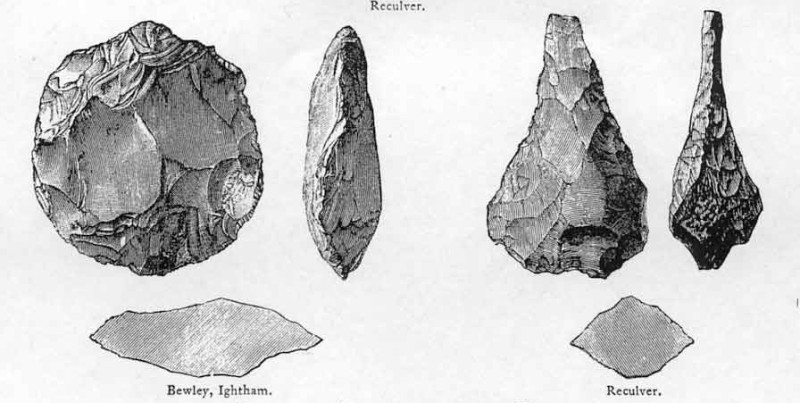

At 1.8 million years ago, another revolution unfolded. The emergent species Homo erectus—an intelligent and durable ancestral human species living from about 1.9 million to 110,000 years ago—ushered in a new technology that archaeologists call the Acheulean. The Acheulean technology is defined by “large cutting tools”—hefty cleavers and axes of a standardized form. These axes were produced through more complex techniques that required reducing a core or a flake from both sides. The typical result was an elegant tear-shaped stone tool that could fit in the hand to slice and chop, pick and pound. The tools were made across Africa, Asia, and Europe for more than 1.5 million years.

The arrival of the Acheulean hand ax documents new cognitive leaps in our ancestral species. The fact that this technology required more complex steps to produce, as well as its symmetry and relatively standardized appearance, all point to the genesis of mathematics, symbolic thinking, and language among Homo erectus. These connections are still hotly debated among researchers.

Some see Acheulean tools merely as the result of geometrical constraints in making a triangular tool; others see its features as merely functional. Some researchers point out that there was not one uniform “tradition” of the tool around the world. It is hard to even say if the celebrated symmetry of the Acheulean hand ax was the intended final form, or if it was merely the product of reworking the tool from each side over time as it was used and resharpened to complete tasks.

Part of the problem with this debate is that there is no widely accepted view of what Acheulean tools did. They have the versatility of a Swiss Army knife, and likely would have been used primarily to butcher animals. However, they also could have been used to dig tubers and roots, and to chop down trees, and they could have been thrown as weapons. Some scientists have controversially suggested that they were like dating profiles—that is, meant to attract sexual partners, symbolic demonstrations of intellectual prowess for potential mates.

Acheulean tools may not mark the arrival of super-intelligence, but this innovative way of engineering stone was complex and required toolmakers to systematically strip off flakes from both sides of a raw chunk of rock. The technology was good enough to last about 1.5 million years.

While there is little evidence that Homo erectus and its later cousin Homo heidelbergensis (a species that lived 700,000 to 200,000 years ago in Europe, Africa, and possibly Asia) had little more than stone tools at their disposal, we begin to see around their time the first signs of a new kind of material world.

At a 400,000-year- old site called Terra Amata in France, archaeologists found the world’s first known shelters: oval structures, likely made by bending pliable saplings, positioning them into postholes, and securing them with rocks at the base. Homo heidelbergensis engineered some of these huts to be 25 feet long. Some contained rock-lined hearths with blackened bones—evidence of the earliest cooking.

Not far away in Germany, archaeologists found three long spears carved from spruce that date to 400,000 years ago. And in Zambia, archaeologists excavated more than 300 fragments of yellow, red, and purple pigments and grinding tools that are 400,000 to 350,000 years old, pointing to the origins of paint, possibly applied to people’s bodies for rituals or as social symbols.

In this same time frame, a Homo erectus artisan living in Germany etched a series of parallel marks into an elephant tibia, pointing to the possibility of art. A cave site in Austria dating to 300,000 years ago yielded a bone point and a wolf incisor each with a hole at their root, seemingly used as pendants for personal ornamentation. Houses, paint, sculpture, body ornaments—our distant hominin ancestors were starting to make our material world.

By 400,000 years ago, Homo neanderthalensis appears in the fossil record, followed by Homo sapiens about 100,000 years later. During this period, yet more sophisticated stone tools were invented: what archaeologists dub the Mousterian tradition. These tools required that the core be more carefully prepared to increase control over the flake’s size, shape, and thickness.

The resulting tools are more diverse than those produced by the Acheulean technique and appear to have been made to be far more specialized for particular functions—not only axes and scrapers, but also triangular points and flakes with a series of sharp notches like a serrated bread knife. Over time, Homo sapiens invented even more advanced stone technologies; for example, our ancestors in South Africa 71,000 years ago used heat-treated stones to make small, delicate bladelets called microliths.

By then, these new stone tools had been joined by a broadening repertoire of material objects. Somewhere between 160,000 and 120,000 years ago, our ancestors in the Near East collected naturally perforated shells and made string to join them together. By 82,000 years ago in Morocco, shell was worked into beads and strung together.

The oldest arrows tipped with stone points were used in South Africa 64,000 years ago. Recovered in the same cave were two slender, pointed bone fragments dating to 61,000 years ago, likely used for stitching animal hides and performing other needlework to produce clothing, blankets, and other coverings. The world’s first known flute (although debated by some) is likely a fragment of bear bone perforated with two holes, recovered in Slovenia and thought to have been played by Neanderthals 50,000 years ago. Beads, arrows, needles, flutes—the modern material world was coming into focus.

__________________________________

Reprinted with permission from So Much Stuff: How Humans Discovered Tools, Invented Meaning, and Made More of Everything by Chip Colwell, published by the University of Chicago Press. Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved.