Masha Gessen: Inside the Gulags of the Soviet Union

By the Time Stalin Died, 2.5 Million People Were Being Held in Camps

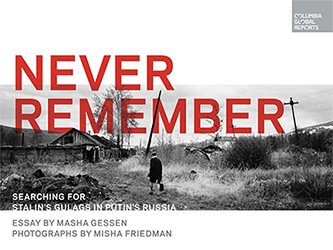

The following is excerpted from Never Remember: Searching for Stalin’s Gulags in Putin’s Russia, by Masha Gessen and Misha Friedman.

The Gulag is nowhere. It was everywhere. The word is an acronym for glavnoye upravleniye lagerey—The Head Directorate of Camps, a bureaucracy so sprawling that Alexander Solzhenitsyn likened it to an archipelago. The Gulag was formed in 1930 in order to put incarcerated Soviet citizens to work. Throughout the 1920s, the number of inmates had fluctuated. On the one hand, the Bolshevik regime strove to isolate its political opponents—it was Soviet Russia that pioneered the idea and the institution of the concentration camp—but on the other hand, the struggling economy could not afford to keep hundreds of thousands behind bars. In the late 1920s, the state experimented with forced labor without incarceration: even convicted murderers often received this kind of penalty.

Still, by 1928 the number of inmates was growing inexorably. The state’s repressive machine was getting stronger: In building a totalitarian system, the need to institute terror overpowered all other considerations, including economic ones. A radical solution was found in creating an entire separate economy of incarceration. The inmates would not simply be put to work in an effort to make the camp self-sustaining, as had been done in the 1920s, but the camps would exist to provide low-cost labor to the state. This was the Gulag.

The Gulag was not an efficient system. In its early years, it was unable to create work for most of the inmates. But the terror machine was gaining speed, shoveling more and more people into the camps. Even though the death rate was extremely high—in 1933 as many as 15 percent of the inmates died of starvation, hypothermia, and disease—and even though the number of executions multiplied—in the Great Terror of 1937–1938 the state executed 681,692, more than 10 times as many as in the preceding 16 years combined—the population of the camps continued to grow. By 1938 it had topped two million. For the next quarter century, the total number of Gulag inmates fluctuated, but by the time Stalin died in 1953, approximately two and a half million people were being held in the camps.

Medvezhyegorsk, Karelia. Photo by Misha Friedman.

Medvezhyegorsk, Karelia. Photo by Misha Friedman.

The Gulag was not a single entity—there were dozens of them: the Gulag of Timber Production, the Gulag of Railroad Construction, and the like. The Gulags contained camp directorates, which in turn contained multiple lagpunkts—“camp units”—the individual camps that made up the archipelago. But the camp itself was a vanishing act: It was created for a specific task—a construction project, a dig, a mine—and when the job was completed, when the tower was built, when the canal was dug, when the mine was depleted, when the forest was decimated—the camp disappeared, often without a trace. The riverside park in front of the hotel in the nuclear-science town of Dubna, outside of Moscow; the 22nd floor of the main building of Moscow State University; the playground in front of the House of Culture in the village of Ust’-Omchug in the Far Eastern region of Kolyma—only a few surviving eyewitnesses knew that a lagpunkt had been there. The eyewitnesses rarely talked, and their memory died with them.

The paperwork that documented a camp’s existence was usually secret. When researchers finally gained access to it, it proved confusing. Camps often moved, taking their names with them. Two mines, hundreds of kilometers apart, would have the same name, that of the camp whose inmates had worked there. If the Bolshevik leader for whom the camp was named fell out of favor, the camp was renamed, confusing the record further. Just as the inmates were not individuals with names but, in the eyes of the regime, an undifferentiated mass with a job, so were the places they temporarily inhabited not places but functions.

It was often up to the inmates themselves to construct shelter out of whatever material was available. Unless timber was not to be found or the nature of the camp’s project dictated otherwise, the barracks were rickety wooden structures that crumpled a couple of years after being abandoned. The wood rotted and melded into the landscape; only the barbed wire remained, though once its own wooden supports collapsed, it would fall on the ground, laying a trap for animals, hunters, and mushroom gatherers.

“Just as the inmates were not individuals with names but, in the eyes of the regime, an undifferentiated mass with a job, so were the places they temporarily inhabited not places but functions.”

One camp lasted. In the Urals, a few hours outside the nearest large city of Molotov (named for Stalin’s foreign minister who brokered the non-aggression pact that enabled the USSR and Nazi Germany to carve up Europe), a camp was built in 1946 to process lumber. Most of the inmates were not what was then called “politicals”: They had not been tried for treason or espionage. Their infractions, whether real or imagined, were what the regime considered to be economic crimes against the state. They had been convicted of theft, fraud, or small-scale embezzlement. Their sentences were shorter than those of the politicals, and when Stalin died in 1953, they were amnestied—unlike the politicals, many of whom had to wait another three to five years. Many of the camps emptied out then and were abandoned to rot. This camp, however, was repurposed to house former secret-police officers: As Khrushchev consolidated power, he cleaned the ranks of the security apparatus. The camp was improved to suit the officers’ needs, reduced as they were behind bars. Toilets were added to the barracks, along with low basins for foot-washing; the earlier generation of inmates had had the use of only two sinks per 125 inmates and had relieved themselves outside. The grounds were also improved.

In 1972, under Brezhnev, a specialized prison colony for law-enforcement officers was built elsewhere in the Urals and the camp was repurposed again. It became one of a dozen and a half places of incarceration—prison colonies, prisons, jails, and psychiatric institutions—used to house the “politicals” of the late Soviet period: human rights activists, pro-independence activists from the constituent republics of the USSR, religious-freedom activists, and underground writers and publishers. In addition, the camp now held men who had been convicted of being wartime Nazi collaborators. All of them were arrested and tried 25 years or more after the war ended; some had indeed assisted the German occupants actively or passively, while others had simply been caught up in the Soviet punitive machine. In the camp’s new incarnation, the indoor toilets were eliminated in favor of new wooden outhouses. Some of the “politicals” were repeat offenders, which made them especially dangerous to the state. They served their time in the Special Zone, a prison within the camp where inmates were confined to cells that allowed in almost no natural light.

The nearest big city to the camp was no longer called Molotov—it had been restored to its pre-revolutionary name, Perm. Accordingly, the camp was now called Perm-36. Nearby prison colonies had the names Perm-35 and Perm-37; Perm itself was a four-hour drive away. In February 1988 several hundred inmates were released from the “political” prisons of the USSR under an amnesty that aimed to end the incarceration of the differently minded. Perm-36 was finally abandoned, left to rot.

Magadan. Photo by Misha Friedman.

Magadan. Photo by Misha Friedman.

“I was blown away,” he told me 24 years later. “I’d been to many colonies, but this was something else. It was archaic. I knew right away that this was left over from the Gulag,” by which he meant the Stalin era. Shmyrov decided to preserve the camp. He and his wife Tatyana Kursina, also a historian, organized security at the site to keep out looters—not that there was much to loot. In 1994, Shmyrov and Kursina started restoring the camp, patching up roofs, righting watchtowers that had fallen over. They put together a team of men from the local village and learned Soviet-era building trades, down to the art of straightening out old nails in order to reuse them. In 1995 Shmyrov quit his professorship and bought a chainsaw. They restored the camp’s sawmill. The team of locals cut down trees in the surrounding woods; some of the wood went to the restoration project and the rest was sold to fund continuing labor. It took them 20 years to restore all 12 of the structures that made up Perm-36, including dormitory barracks, the solitary-confinement building, the sawmill, the guards’ houses, the bathhouse, and the infirmary.

In 2005, Shmyrov and Kursina organized a festival for singer songwriters. The genre had been popular in the Soviet underground, so it seemed appropriate. They called it the Sawmill. It turned into an annual event, and an odd one: part NGO congress, part political-prisoner reunion, part rock concert, part curiosity. By the 2010s, it was drawing as many as 15,000 people, who set up camp in the surrounding fields and forests—Shmyrov had bought the land, which was cheaper than dirt. Volunteers led short tours of the camp itself, which, during the course of the festival, seemed to become something of a Gulag theme park.

In 2011 the regional governor, who harbored the unusual ambition of securing for Perm the title of a European Cultural Capital, offered Shmyrov and his team the resources and status to turn Perm-36 into a museum. Shmyrov and Kursina created several exhibition halls in the camp and contracted with an American museum-design firm for a full-scale contemporary interactive exhibit. Though for Shmyrov, the museum project was secondary: His mission was preservation. When Roginsky, the head of the Memorial Society in Moscow and a former political prisoner, told Shmyrov that the restored Perm-36 felt exactly like a real Soviet-era prison camp, Shmyrov accepted it as the ultimate compliment.

__________________________________

From Never Remember: Searching for Stalin’s Gulags in Putin’s Russia. Used with permission of Columbia Global Reports. Text copyright © 2018 by Masha Gessen. Photographs copyright © 2018 by Misha Friedman.

Masha Gessen

Masha Gessen is the author of eleven other books, including the National Book Award-winning The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia and The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin. A staff writer at The New Yorker and the recipient of numerous awards, including Guggenheim and Carnegie fellowships, Gessen teaches at Bard College and lives in New York City.