Marlon James on the Subversive Art of the Dancehall Sign

Looking at Three Decades of Jamaican Poster Art

The following is from Serious Things a Go Happen: Three Decades of Jamaican Dancehall Signs, by Maxine Walters, available from Hat & Beard Press.

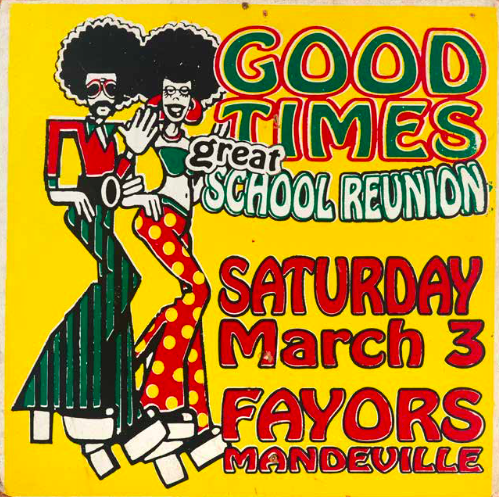

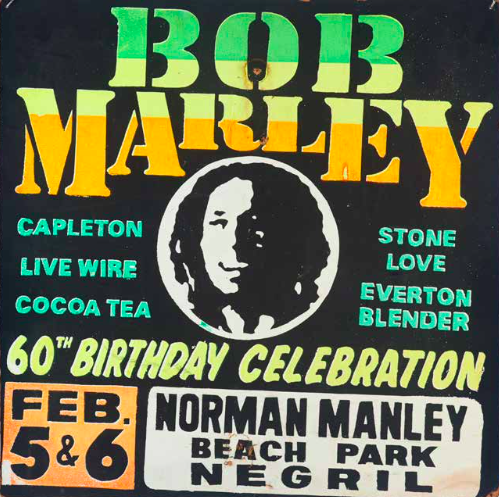

If hip-hop’s visual language is graffiti, then dancehall’s visual language is the sign, the event poster—the notice that big t’ings a gwaan down di street. Take the analogy further and the differences are as noteworthy as the similarities: both are signifiers, even though graffiti signifies the artist himself, while the dancehall sign signifies an event. One is mostly expression, while the other is mostly communication. Both are art forms that came out of nothing, with almost no precedent, and both remain the only art in each genre that feels like the sound of each genre. Street art, outsider art, but more than anything, outlaw art.

But the comparison can only go so far, since dancehall is its own cultural phenomenon, and while we could waste time playing spot the influence, we forget that the music sprung almost fully formed, on the streets of Kingston. Dancehall art in turn could never have been made for any other musical genre, not even roots reggae, which was already on its way to being established music. There’s too much do-it-yourself spirit here. Too much plundering of whatever materials available, too much info scribbled and scrawled on the go, too much of function over form, and too much of the spunky creativity of a people, sometimes without resources to create.

It would be a surprise to many of the people who made these signs that this medium, where function triumphs over form every time, should emerge as its own art, with its own aesthetic—though if you are going to bring words like “aesthetic” into it, you’ve already missed the point. Back when I was a kid in the 70s, a dancehall sign felt like subversive code, an invite to something to which I would never be allowed to go. Something that to me just looked like Jamaica. You’d be surprised, less than 20 years after independence, how hard it was to find culture as you saw it in the street. For my parents’ generation, Dancehall wasn’t even culture.

A session wasn’t a place for decent people. Nobody was going to open “Shore Vibes,” with prayer, no church sister was going to be at “Dutty Fridaze,” at least not in plain sight. And you certainly wouldn’t have heard any of those songs on the radio. The people who put them on always traded in alter-egos—Mumsy as Simone! Keisha as Sexy!—that electrified my imagination. These were Reggae events, where the musician wasn’t the star so much as the record itself. And these were posters where the sound systems, like KILLAMANJARO, took on mythic status.

But all this role-playing and mythmaking undercuts what is so special about the dancehall sign, which is its invitation to the realest of the real. People you might know, inviting you to come nice up de dance. Security: Your best behavior, meaning this event is ours, and good times are here to stay if we protect it. The dancehall poster is visual proof that dancehall happened and continues to happen. And proof of dancehall’s vitality is not in music videos, or Instagram posts, or how many rappers invite the hottest DJ to guest on their single. The proof is that sign that just went up on the lamp post, about that party next week that going bruk it dung, right down the street.