Marcial Gala on Writing Cuba and Reworking The Iliad

“My literary project is Cienfuegos: world capital.”

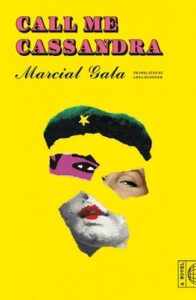

Marcial Gala understands that The Iliad’s narrative force is its ability to both describe an all-consuming war and present the very human characters that make up that battle. Gala picks up where Homer and many others left off with a psychological portrait of the prophet, Cassandra, who also gives his newest book its eponymous title.

Except we are not in antiquity but the city of Cienfuegos in the 1980s where we meet Raul and learn of his doomed ability to see the future. He knows he is going to die on a remote base in Angola, but he is both unwilling and unable to change his fate. Raul, like Cassandra, is a victim of both personal and political circumstances. To understand those circumstances I talked to Marcial about myths, growing up in Cuba, and writing about Cienfuegos, which I once thought was a minor city. This conversation took place over Zoom and Marcial’s answers were translated by Anna Kushner.

*

Samuel Jaffe Goldstein: Tell us about yourself, a brief overview of who you are and how you came to write Call Me Cassandra?

Marcial Gala: I was born in Havana in the same mansion where poet Julián del Casal died, only by then, it was an abandoned place, divided up into rooms, where I think that the poet’s ghost appeared to me at night because I was living through a kind of continual distress. Then I moved to Cienfuegos and always relied on reading as a kind of second skin in which to take shelter. I studied architecture mainly due to a lack of a vocation for anything else. While I was still at the university, I began to write. The Iliad was, in high school, one of my bedside books. Achilles and Hector were so familiar to me, along with Prince Andrei from War and Peace. In sum, I could practically say that I was destined to write a book like Call Me Cassandra.

SJG: We have this mythology about the war in Angola because it was against apartheid government. Your book complicates that picture.

MG: The majority of the Cuban soldiers being sent to Angola were not professionals. They were poorly trained and very young recruits, often 16 or 17 years old. The experience for the Cuban veterans was terrible. These recruits were sent back to Cuba after the war without any kind of support system. They were often just dropped off at a bus station with enough money for a bus ticket back to their hometown. They received no homecoming, no pensions, no psychological treatment, nothing. You couldn’t say you weren’t willing to go, because then you were subject to these acts of repudiation.

Something that contributed to Cuba’s success, which is lacking now, is the revolutionary fervor that people genuinely felt at this period of time.

People would physically beat those who would refuse to go to the war in Angola. A famous army slogan at the time was, “If I march forward, follow me. If I stop, push me. If I take a step back, kill me.” There was no room for disrupting your recruitment, what you were supposed to do, and no recognition of what you had been through once you were sent back to Cuba.

SJG: How did Cuba win?

MG: Something that contributed to Cuba’s success, which is lacking now, is the revolutionary fervor that people genuinely felt at this period of time. The Mariel Boatlift had happened but a lot of people on the island still believed in the project of socialism, in the moral superiority of socialism, they felt sympathy for the world proletariat movement. Especially against the apartheid regime in South Africa. All of this contributed to a people who believed in the cause they were fighting for. If you were younger and did not know what you were doing so far from home, being on the right side was a strong motivator.

SJG: There are a lot of expectations that readers might have of a writer from Cuba. How do you want people to think about your contribution?

MG: There is an adage that “the center of the world is everywhere but also nowhere at once.” The challenge was to turn this unknown city, Cienfuegos, into a literary city. You could draw a parallel between the small stature of the main character, Raul, and the city of Cienfuegos. Creating a Cuban reality beyond Havana, of Cienfuegos and Angola. To make a spider’s web, weaving in more universal themes going back to Greece and the Iliad. This basic pillar of Western literature. It is a book that goes beyond its geographic setting in exploring themes of life, death, time, and falling in and out of love.

SJG: Both Call me Cassandra and Black Cathedral are set in Cienfuegos. What drives you to continually write about this city?

MG: My literary project is Cienfuegos: world capital. I was born in Havana before there was a lot of focus on renovating Old Havana. A lot of what people see now when they travel there was created after the time I was born. When I lived there it was a very marginalized part of the city and I remember once biking by a dead body on the street. It was not a pleasant place to live. At some point my father was offered a house in Cienfuegos through his job and relocated there.

The first time I got a view of the bright blue beautiful ocean there it had nothing to do with my view of the water in Havana. Havana’s water was murky and dirty. That oceanic feeling was my impetus to start writing about Cienfuegos. My other novel that has been translated into English, The Black Cathedral, only lightly resembles Cienfuegos. Call Me Cassandra is set in the classic Cienfuegos and all of its social registers and characteristics that make it a microcosm of what is going on in Cuba.

SJG: Is it hard to write a book about Cuba without writing about its relationship with the United States?

MG: It can be done. My most recent novel, Bare feet, is set in a time in which there was still slavery in Cuba and is not at all about the United States. In a contemporary novel, it is difficult. The second largest city inhabited by Cuban people is Miami. Cuba is part of the United States’ orbit. Turn on the Cuban news and see that the majority of things reported about are events occurring in the United States. Because they often affect the island. The Cuban government has also used this idea of the United States to their own advantage to create this idea of the citadel, of this walled island that always has to protect itself from this aggressor to the north. It is used as an excuse for things it has done.

The title Call Me Cassandra makes the reader wonder who is actually talking to us in this novel?

SJG: In Call Me Cassandra, Raul/Cassandra can see the future, but that future is very personal. Why do you keep it so small?

MG: It is part of the literary pact that Cassandra would be focusing on these smaller predictions, that is what you see playing out in the classics of Greek literature. You see Achilles ask how he will die, but you never get larger information about historical-political events. It doesn’t make sense for Cassandra to be talking about larger things, it would be a different book. The ideal reader of Cassandra’s words is the omnipotent Zeus. Zeus knows how things turn out but has this gossipy interest in the smaller lives of people. Zeus does not care how the U.S.—Cuban conflict ends, because Zeus is interested in little Cassandra.

SJG: Does keeping prophecy small and personal make the outcome more tragic? Do we lose something when we expand the narrative wider?

MG: Yes, I think so. For me, the novel is, above all, existentialist. It’s a novel whose currency could be “hell is other people” and Cassandra is drowning in her own personal hell, in which there is no way out, she doesn’t even blame father Zeus for making her be reborn in such an inappropriate place, or even Apollo who is so deceitful. She is someone who is resigned to her fate as a propitiatory victim. You could almost say that the novel is the gospel according to Cassandra, just like the gospel tells only the story of what happened to the apostles and to Jesus himself, without us knowing anything about the socio-political situation of the ancient world.

SJG: Why is it important to tell the gospel according to Cassandra?

MG: The title Call Me Cassandra makes the reader wonder who is actually talking to us in this novel? This character reflects what people see. In Raul, his mom sees her deceased sister, Nancy. The captain in Angola looks at him and sees his wife who is back in Cuba. It evokes the “Call me Ishmael” line in Moby-Dick. We don’t know if the person telling us she is Cassandra is actually Cassandra. There are these layers of ambiguity in the telling of the prophecies. Then there’s the bigger issue that there is not even a vocabulary of what Raul is going through as a soldier in the 1980s. To see into the future would not even be translatable.

SJG: Throughout the book The Iliad is constantly referenced and there is a dichotomy between the personal nature of Raul and this all encompassing war. Was it hard to write about that dichotomy?

MG: I am taking this minor character from a major work and dropping her into this story that Iwanted to tell about Cuba. Playing with the changes in reality, in which Raul is going back and forth across time. The war in Angola is a backdrop for exploring the intolerance of the time period and the personal tragedy of this specific character who is not an epic hero. If anything he is an anti-hero, he is someone who goes in search of his own death but not the way Achilles did by seeking glory. It is not a heroic death in any way. It’s more like this character is imprisoned in their own self, is passive, and incapable of any transformation.

SJG: We think of modern literature as being the offspring of The Odyssey, but what is about The Iliad for you that makes it worth being the ancestor of this book?

MG: Ah, The Iliad is a text chock full of echoes and just like Shakespeare’s tragedies, there are moments of great psychological scope and moments of great drama. I think nothing like The Iliad was ever written until Tolstoy showed up with War and Peace. I don’t know if there will be something like it in the future.

SJG: Why write about fate even though we know the outcome will not change?

MG: You do know that this character will die, but the question is how. That’s a characteristic of the human condition. We cannot escape our fate, and we spend all this time wondering about its arrival. What makes a good story is the how. The story itself is something that you weave by creating this atmosphere, invoking the idea of Lezama Lima’s eternal return, and using this to explore the circumstances of Raul. Raul was born in Cuba in the wrong body at the wrong time. He is imprisoned within this body and condemned by this homophobic society.

SJG: You describe Achilles as Shango from the Yoruba religion. Yet you keep it focused on Greek mythology. Why continue with the Greek tradition instead of using Yoruba myths?

MG: Perhaps in another novel I will make the leap to close this circle. I am the type of person who, in a way, writes to honor what I have read and I had that outstanding debt with Greek mythology, besides coming from a family of devout atheists and my relationship with gods and orishas being more literary than anything else.

SJG: We usually look down at treachery, but in your book we should not be looking down at the treachery of Raul.

MG: All human beings are imprisoned in their context. Raul must betray himself, because there is no ability for him to be truly who he is. If Raul said, “I’m actually Rauli wearing this dress” people would have started beating or stoning Rauli to death. It was mere survival to live this kind of betrayal. Then any of the expressions of dissidence also involve betrayal against these structures. There’s a quote from Kurosawa’s Ran, “In this current crazy world, going crazy is sane.”

__________________________________

Marcial Gala’s Call Me Cassandra is available now from Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Samuel Jaffe Goldstein

You can find Sam Jaffe Goldstein on twitter @sjaffegold.