Many Voices, Many Truths: On the Benefits of Polyvocal Stories

How Hannah Michell Transcends the Single Perspective

Nothing intrigues me more than when people disagree over the same set of facts, or about people they know in common. These disagreements are as revealing of character as they are about the disagreements themselves. This variation in perspectives, informed by our own experiences, has led me to the conclusion that the stories we tell ourselves, especially those about our own lives, may not be the stories that others tell of us.

In the years following my parents’ separation, I puzzled over the details to attempt to understand the story of their divorce. I understood the plot—my father had met a young woman and there was an affair, then a child was born, then when I learned of this half-brother some time later my parents divorced—but I did not understand the characters. I only comprehended my version of events—for years I had lived in a house that felt heavy with secrets and my father had abandoned me. Unhappy with this story, I sought to understand the different psychological states of those involved.

My desire to better understand character has led me to interrogate the people around me—often overstepping boundaries, prying into their private lives, their thoughts and responses to events, what motivates their most altruistic acts, their behavior and habits when they think no one else is watching.

As a writer, I struggle to contain my fiction in a single point of view. Perspective fascinates me. The close third point of view allows the reader to deeply engage with the contrasting worldview of different characters by momentarily seeing the world through their eyes—what they choose to notice, what they choose to disregard or elude, as well as their understanding of their motivations. And in this intimate vulnerability even unlikeable characters generate sympathy for themselves. As the adage goes, even villains are the heroes of their lives.

If individuals’ accounts of their lives are full of evasions, then it seems possible that a singular narrative about a nation’s origins and history are likely to be unreliable. I wanted to write a novel about the dominant story told about South Korea’s recent history, describing its ascendance from the second poorest country in the world after the Korean War, to the 11th largest economy it is today as an “economic miracle”. It felt to me that this was the kind of mythology a country can espouse when it ignores other unpleasant realities—such as that of labor exploitation and human rights abuses under dictatorship.

The multi-voice novel is a form that resists the idea that there can only be one account of history.

Originally, I had planned to write Excavations with only a single voice—that of a Chairman of a major company who personified the rags to riches story of the Korean economy. Inspired by an autobiography of a famous Korean Chairman of a now bankrupt company, I sought to replicate the persuasive and inspiring voice of this leader in my fiction. I wanted this Chairman to be likable, but for his account of his life to be full of distortions. However, after wrestling with multiple drafts, I realized that hinting at his unreliability was not enough—it would be more powerful to show, through contrasting perspectives, exactly where his version of events might be contested.

In the Chairman’s sections of the novel, he speaks of his sons with thoughtfulness and devotion. However, when the main protagonist of the novel, ex-journalist and mother of two young children, Sae, begins to investigate the circumstances of the collapse of a skyscraper that the Chairman has built, his own narrative that he has always prioritized his own family begins to crumble. In fact, the evidence that she unearths calls into question whether he really knew his sons at all.

Another character’s account, Myonghee, challenges the Chairman’s account of being a family man by demonstrating his clear preference for sons over daughters. After seeing her struggle with the many difficult decisions she must make to survive economically after being discarded by the Chairman in a society that shuns single mothers, we see a different version to the “economic miracle”—one that exploited women as they tried to support themselves.

The multi-voice novel is a form that resists the idea that there can only be one account of history. It acknowledges that a person’s gendered, social and racial position may yield different experiences in response to the same event. This layering of voices and perspectives can reveal the rich tapestry of people who do not exist in isolation, but for better or worse, are deeply affected by each other.

Recently, I began a piece of writing that seemed to lead me somewhere, back to the puzzle of my parents’ divorce. It allowed me, at last, to transcend my own perspective and understand something new about the cast of characters that had been involved. In the scene, a man walks into a bar. He is weary, not from a hard day at work, but from the loneliness of living in a country that feels completely alien to him. He orders a drink from a young woman whose vulnerability he finds strangely moving.

By the time she has set down the drink, she too has noticed the warm kindness in his eyes. Despite herself, she finds herself thinking that he might take her far from this place to another country where she can begin again. She is tired of fending for herself. She feels a surge of desire and possibility, for a family of her own, something she has not dared to hope for since she was orphaned at the age of nine.

By the end of the evening, she is filled with a sense of warmth and happiness that she has not felt in a long time. It is this feeling that she wishes to hold on to. It is this that she thinks of as she asks to see him again. She is not thinking of the four year old girl across the city who wakes from a nightmare asking for her father. She does not know that this girl exists.

__________________________

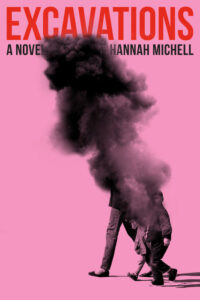

Excavations by Hannah Mitchell is available now via One World.

Hannah Michell

Hannah Michell grew up in Seoul. She studied anthropology and philosophy at Cambridge University and now lives in California with her husband and children. She teaches in the Asian American and Asian Disapora Studies Program at the University of California, Berkeley.